-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 169

About TLS, DNS, Encryption and OPSEC concepts

The contents here are for beginners, to learn the basics of TLS, encrypted connections and some preliminary OPSEC (Operational security) concepts.

Let's talk about DNS first. Whether you are using Secure DNS such as DNS over HTTPS or using plain text DNS (Default port: 53), the domain name is the only piece of information that the DNS server provider will see. DNS does not deal with URLs, only domain names.

E.g., in this URL, anything after the first / is inaccessible to the DNS server.

Github.com/HotCakeX/Harden-Windows-Security

The DNS provider will know that you are accessing GitHub.com but won't know which repository on GitHub.com you are visiting.

-

DNS doesn't resolve URLs, only enables the DNS client to find the IP Address of the server part of the URL, the rest is handled by HTTP protocol/request. The part before the slash is the DNS-provided hostname or an ordinary IP address. The part after the slash indicates the application on that host. DNS does not deal with anything after the slash at all.

-

Anything in the URL that is not domain name is encrypted as part of the HTTP request, which uses TLS for encryption and that's why it's HTTPS. They are invisible to the DNS server and anyone else other than the webserver hosting the website you are visiting.

When you are using VPN or proxies, it's important to make sure there is no DNS leakage. Properly implemented and configured VPNs/Proxies don't have this problem.

The most practical way to see if you have DNS leak while using a VPN/Proxy is to use Wireshark to monitor your outbound connections on the edge of your network. Simply type dns in the Wireshark's display filter bar and observe the results. If you are using a proper VPN/Proxy or if you are using Secure DNS such as DoH or DoT, then you shouldn't see any results because that keyword only displays plain text DNS over the default port 53.

DNSSEC by itself without using DoH/DoT can be downgraded. If you're using DoH or DoT you must be safe as long as you are using a trusted DNS provider and your certificate authority storage is not poisoned/compromised.

Certain countries with dictatorship or theocracy governments make people install their own root certificate to perform TLS-termination and view their data in plain-text even when HTTPS is being used. One example is what happened in Kazakhstan.

Certain applications install root certificates, such as 3rd party antiviruses. They are all equally dangerous and must be avoided.

Using DNS-over-TLS or DNS-over-HTTPS mitigates some privacy leaks, because now the ISP won't have the domain you are visiting, but only the IP address. It's possible that more than one site uses the same IP address, so in some cases, it's not possible to say for sure that you are visiting SiteA.com when SiteB.com shares the same IP (Unless you are using TLS v1.2 which leaks Certificate's common name, more on that later), and high-traffic sites usually employ a CDN (content delivery network) to distribute traffic, and the IP they use are not the site's IP, but an IP belonging to the CDN (like CloudFlare or Akamai).

Website owners use CDNs like Cloudflare for two purposes:

-

Best user response time by using the nearest server.

-

Load-balancing in case of the nearest server being overloaded (DDoS and more) and then pointing to the next-nearest server.

Browsers such as Microsoft Edge only support DNS over HTTPS. Windows supports DNS over HTTPS and DNS over TLS.

DNS over HTTPS is preferred because by default it uses the same port 443 as the rest of the HTTPS traffic on the Internet, that makes it harder to be detected and blocked. DNS over TLS on the other hand uses TCP port 853 by default and a filter on that port would block DNS over TLS entirely, whereas blocking port 443 is impractical as it essentially cripples the entire Internet.

DNS caches, just like DNS itself, only map domain names to values ('A' records), never the other way around.

Both the DNS cache, and the DNS system as a whole, only care that bing.com points to 1.2.3.4, not that the address "points" back.

Entries in the DNS cache look exactly like entries in authoritative DNS servers, with domain name as the lookup key.

Windows components (Tested on Windows 11 22H2) rely on TLS 1.2, and that makes them dependent on ECC Curves. So, when enforcing TLS 1.3 only for Schannel, Windows components stop working.

TLS 1.3 cipher suites don't require ECC curves.

NistP256 ECC curve is a must have, otherwise Windows update won't work.

nistP521 is the best ECC curve in terms of security, but curve25519 is also the best non-Nist one, which is also secure and popular.

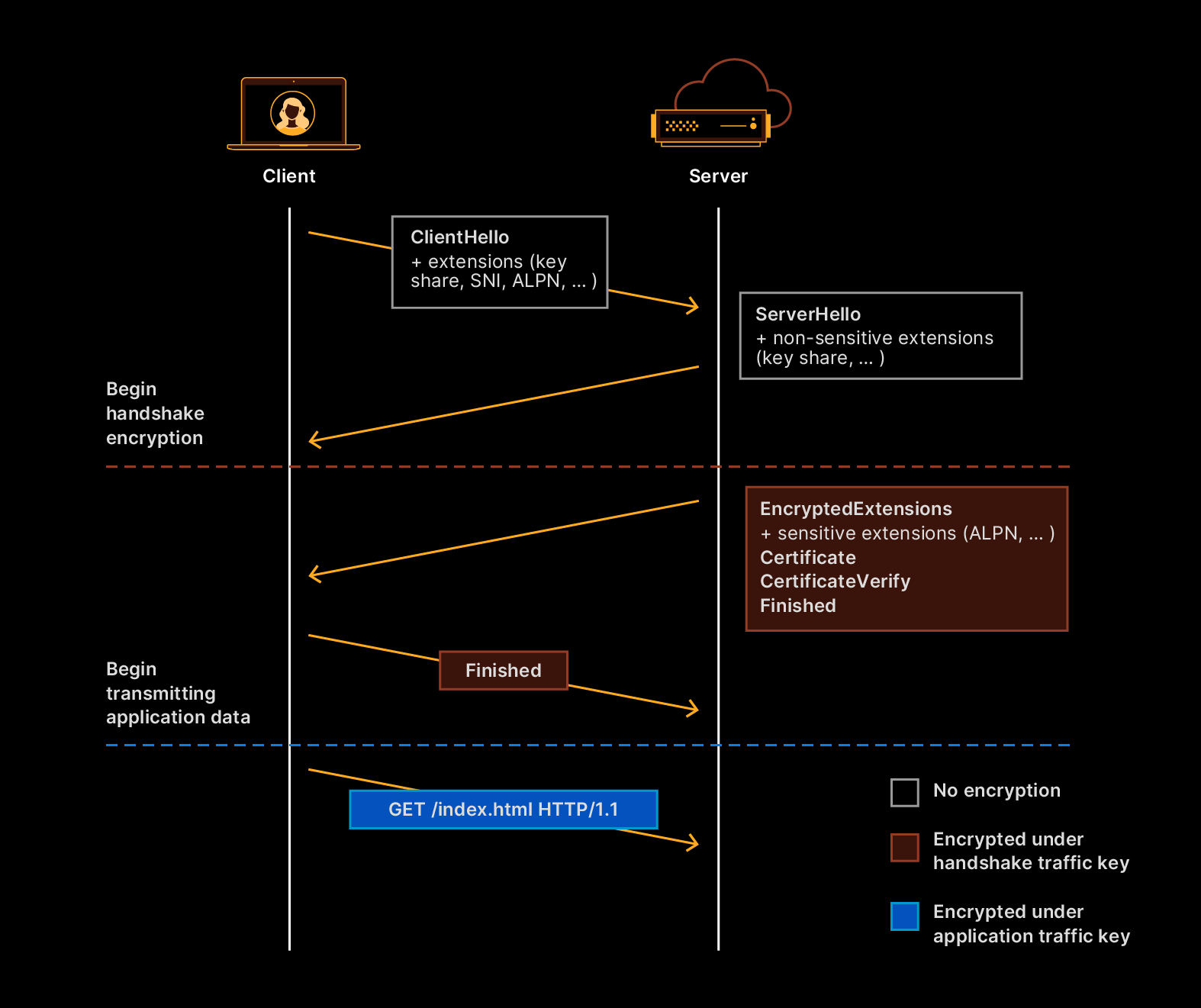

Handshake messages contain the certificates (both from server and client), and they are encrypted in TLS 1.3, which means that you cannot see these without breaking the encryption.

SNI, which is part of the handshake, is still unencrypted even in TLS v1.3. The only way to encrypt SNI is to use ECH (Encrypted Client Hello).

Assuming you are operating in a hostile country (E.g, China, Russia, Iran), you must be aware of the following information to keep your digital footprint minimal.

There are 4 pieces of information that can reveal which websites/apps/services you use, to the ISP/government.

Avoid using plain text DNS as much as you can. Use DNS over HTTPS for security and anonymity. Governments can block well-known servers quickly, you can however self-host on a private cloud or use a serverless DNS to have access to a new endpoint for DoH over a newly setup domain.

If plain text DNS over port 53 is used, and you are not using a proper VPN like OpenVPN or WireGuard, or you are using proxy, then eavesdropper can see the website domain/sub-domain you are visiting. If you use secure DNS like DNS over HTTPS, then DNS becomes fully encrypted and all they can see is the domain name of the Secure DNS server as well as the IP addresses of the websites you connect to.

Use TLS v1.3. When using TLS v1.3, the certificate part of the HTTPS connection is encrypted and none of its details are visible to the eavesdropper. TLS v1.2 handshakes do not encrypt the certificates, resulting in the common name and the website you are visiting to be revealed to the eavesdropper.

The full path to a web page or web resource is sent over HTTP protocol, so if website uses HTTPS, it's all encrypted.

When using HTTPS, the path and query string (everything after TLD and slash /) is encrypted and not available to anybody but the client and server, the answer is encrypted as well.

This is the most important part. Even after using:

-

HTTPS to encrypt the full URL path

-

DoH to encrypt the DNS

-

TLS v1.3 to encrypt the certificate

If you don't use a proper VPN, SNI can still reveal the domain and sub-domain of the website you are visiting to the eavesdropper. To secure that, the browser and the website must support ECH (Encrypted Client Hello) or use proper VPN like OpenVPN or WireGuard.

Interesting and useful columns to add to the Wireshark GUI for better visibility into your network connections:

-

Use

tls.handshake.type == 11to filter certificates, only works for TLS v1.2 and below since they don't encrypt that part of the handshake. -

Use

ssl.handshake.extension.type == "server_name"to filter SNI or Server Name Indication. More info (When using VPN, you either shouldn't be seeing any SNI at all or only see the SNI that belongs to the VPN server's domain.) -

Cipher Suites is also an interesting column to add to your Wireshark profile.

- Create AppControl Policy

- Create Supplemental Policy

- System Information

- Configure Policy Rule Options

- Simulation

- Allow New Apps

- Build New Certificate

- Create Policy From Event Logs

- Create Policy From MDE Advanced Hunting

- Create Deny Policy

- Merge App Control Policies

- Deploy App Control Policy

- Get Code Integrity Hashes

- Get Secure Policy Settings

- Update

- Sidebar

- Validate Policies

- View File Certificates

- Introduction

- How To Generate Audit Logs via App Control Policies

- How To Create an App Control Supplemental Policy

- The Strength of Signed App Control Policies

- App Control Notes

- How to use Windows Server to Create App Control Code Signing Certificate

- Fast and Automatic Microsoft Recommended Driver Block Rules updates

- App Control policy for BYOVD Kernel mode only protection

- EKUs in App Control for Business Policies

- App Control Rule Levels Comparison and Guide

- Script Enforcement and PowerShell Constrained Language Mode in App Control Policies

- How to Use Microsoft Defender for Endpoint Advanced Hunting With App Control

- App Control Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Create Bootable USB flash drive with no 3rd party tools

- Event Viewer

- Group Policy

- How to compact your OS and free up extra space

- Hyper V

- Overrides for Microsoft Security Baseline

- Git GitHub Desktop and Mandatory ASLR

- Signed and Verified commits with GitHub desktop

- About TLS, DNS, Encryption and OPSEC concepts

- Things to do when clean installing Windows

- Comparison of security benchmarks

- BitLocker, TPM and Pluton | What Are They and How Do They Work

- How to Detect Changes in User and Local Machine Certificate Stores in Real Time Using PowerShell

- Cloning Personal and Enterprise Repositories Using GitHub Desktop

- Only a Small Portion of The Windows OS Security Apparatus

- Rethinking Trust: Advanced Security Measures for High‐Stakes Systems

- Clean Source principle, Azure and Privileged Access Workstations

- How to Securely Connect to Azure VMs and Use RDP

- Basic PowerShell tricks and notes

- Basic PowerShell tricks and notes Part 2

- Basic PowerShell tricks and notes Part 3

- Basic PowerShell tricks and notes Part 4

- Basic PowerShell tricks and notes Part 5

- How To Access All Stream Outputs From Thread Jobs In PowerShell In Real Time

- PowerShell Best Practices To Follow When Coding

- How To Asynchronously Access All Stream Outputs From Background Jobs In PowerShell

- Powershell Dynamic Parameters and How to Add Them to the Get‐Help Syntax

- RunSpaces In PowerShell

- How To Use Reflection And Prevent Using Internal & Private C# Methods in PowerShell