This is release v1.7.3 of OSPRay. For changes and new features see the changelog. Also visit http://www.ospray.org for more information.

OSPRay is an open source, scalable, and portable ray tracing engine for high-performance, high-fidelity visualization on Intel® Architecture CPUs. OSPRay is released under the permissive Apache 2.0 license.

The purpose of OSPRay is to provide an open, powerful, and easy-to-use rendering library that allows one to easily build applications that use ray tracing based rendering for interactive applications (including both surface- and volume-based visualizations). OSPRay is completely CPU-based, and runs on anything from laptops, to workstations, to compute nodes in HPC systems.

OSPRay internally builds on top of Embree and ISPC (Intel® SPMD Program Compiler), and fully utilizes modern instruction sets like Intel® SSE4, AVX, AVX2, and AVX-512 to achieve high rendering performance, thus a CPU with support for at least SSE4.1 is required to run OSPRay.

OSPRay is under active development, and though we do our best to guarantee stable release versions a certain number of bugs, as-yet-missing features, inconsistencies, or any other issues are still possible. Should you find any such issues please report them immediately via OSPRay’s GitHub Issue Tracker (or, if you should happen to have a fix for it,you can also send us a pull request); for missing features please contact us via email at [email protected].

For recent news, updates, and announcements, please see our complete news/updates page.

Join our mailing list to receive release announcements and major news regarding OSPRay.

The latest OSPRay sources are always available at the OSPRay GitHub

repository. The default master

branch should always point to the latest tested bugfix release.

OSPRay currently supports Linux, Mac OS X, and Windows. In addition, before you can build OSPRay you need the following prerequisites:

-

You can clone the latest OSPRay sources via:

git clone https://github.com/ospray/ospray.git -

To build OSPRay you need CMake, any form of C++11 compiler (we recommend using GCC, but also support Clang and the Intel® C++ Compiler (icc)), and standard Linux development tools. To build the example viewers, you should also have some version of OpenGL.

-

Additionally you require a copy of the Intel® SPMD Program Compiler (ISPC), version 1.9.1 or later. Please obtain a release of ISPC from the ISPC downloads page. The build system looks for ISPC in the

PATHand in the directory right “next to” the checked-out OSPRay sources.1 Alternatively set the CMake variableISPC_EXECUTABLEto the location of the ISPC compiler. -

Per default OSPRay uses the Intel® Threading Building Blocks (TBB) as tasking system, which we recommend for performance and flexibility reasons. Alternatively you can set CMake variable

OSPRAY_TASKING_SYSTEMtoOpenMP,Internal, orCilk(icc only). -

OSPRay also heavily uses Embree, installing version 3.2 or newer is required. If Embree is not found by CMake its location can be hinted with the variable

embree_DIR. NOTE: Windows users should use Embree v3.2.2 or later.

Depending on your Linux distribution you can install these dependencies

using yum or apt-get. Some of these packages might already be

installed or might have slightly different names.

Type the following to install the dependencies using yum:

sudo yum install cmake.x86_64

sudo yum install tbb.x86_64 tbb-devel.x86_64

Type the following to install the dependencies using apt-get:

sudo apt-get install cmake-curses-gui

sudo apt-get install libtbb-dev

Under Mac OS X these dependencies can be installed using MacPorts:

sudo port install cmake tbb

Under Windows please directly use the appropriate installers for CMake, TBB, ISPC (for your Visual Studio version) and Embree.

Assume the above requisites are all fulfilled, building OSPRay through CMake is easy:

-

Create a build directory, and go into it

mkdir ospray/build cd ospray/build(We do recommend having separate build directories for different configurations such as release, debug, etc).

-

The compiler CMake will use will default to whatever the

CCandCXXenvironment variables point to. Should you want to specify a different compiler, run cmake manually while specifying the desired compiler. The default compiler on most linux machines isgcc, but it can be pointed toclanginstead by executing the following:cmake -DCMAKE_CXX_COMPILER=clang++ -DCMAKE_C_COMPILER=clang ..CMake will now use Clang instead of GCC. If you are ok with using the default compiler on your system, then simply skip this step. Note that the compiler variables cannot be changed after the first

cmakeorccmakerun. -

Open the CMake configuration dialog

ccmake .. -

Make sure to properly set build mode and enable the components you need, etc; then type ’c’onfigure and ’g’enerate. When back on the command prompt, build it using

make -

You should now have

libospray.soas well as a set of example application. You can test your version of OSPRay using any of the examples on the OSPRay Demos and Examples page.

On Windows using the CMake GUI (cmake-gui.exe) is the most convenient

way to configure OSPRay and to create the Visual Studio solution files:

-

Browse to the OSPRay sources and specify a build directory (if it does not exist yet CMake will create it).

-

Click “Configure” and select as generator the Visual Studio version you have, for Win64 (32 bit builds are not supported by OSPRay), e.g. “Visual Studio 15 2017 Win64”.

-

If the configuration fails because some dependencies could not be found then follow the instructions given in the error message, e.g. set the variable

embree_DIRto the folder where Embree was installed. -

Optionally change the default build options, and then click “Generate” to create the solution and project files in the build directory.

-

Open the generated

OSPRay.slnin Visual Studio, select the build configuration and compile the project.

Alternatively, OSPRay can also be built without any GUI, entirely on the console. In the Visual Studio command prompt type:

cd path\to\ospray

mkdir build

cd build

cmake -G "Visual Studio 15 2017 Win64" [-D VARIABLE=value] ..

cmake --build . --config Release

Use -D to set variables for CMake, e.g. the path to Embree with

“-D embree_DIR=\path\to\embree”.

You can also build only some projects with the --target switch.

Additional parameters after “--” will be passed to msbuild. For

example, to build in parallel only the OSPRay library without the

example applications use

cmake --build . --config Release --target ospray -- /m

The following API documentation of OSPRay can also be found as a pdf document.

For a deeper explanation of the concepts, design, features and performance of OSPRay also have a look at the IEEE Vis 2016 paper “OSPRay – A CPU Ray Tracing Framework for Scientific Visualization” (49MB, or get the smaller version 1.8MB). Also available are the slides of the talk (5.2MB).

To access the OSPRay API you first need to include the OSPRay header

#include "ospray/ospray.h"

where the API is compatible with C99 and C++.

In order to use the API, OSPRay must be initialized with a “device”. A device is the object which implements the API. Creating and initializing a device can be done in either of two ways: command line arguments or manually instantiating a device.

The first is to do so by giving OSPRay the command line from main() by

calling

OSPError ospInit(int *argc, const char **argv);

OSPRay parses (and removes) its known command line parameters from your

application’s main function. For an example see the

tutorial. For possible error codes see section Error

Handling and Status Messages. It

is important to note that the arguments passed to ospInit() are

processed in order they are listed. The following parameters (which are

prefixed by convention with “--osp:”) are understood:

ospInit.

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

--osp:debug |

enables various extra checks and debug output, and disables multi-threading |

--osp:numthreads <n> |

use n threads instead of per default using all detected hardware threads |

--osp:loglevel <n> |

set logging level, default 0; increasing n means increasingly verbose log messages |

--osp:verbose |

shortcut for --osp:loglevel 1 |

--osp:vv |

shortcut for --osp:loglevel 2 |

--osp:module:<name> |

load a module during initialization; equivalent to calling ospLoadModule(name) |

--osp:mpi |

enables MPI mode for parallel rendering with the mpi_offload device, to be used in conjunction with mpirun; this will automatically load the “mpi” module if it is not yet loaded or linked |

--osp:mpi-offload |

same as --osp:mpi |

--osp:mpi-distributed |

same as --osp:mpi, but will create an mpi_distributed device instead; Note that this will likely require application changes to work properly |

--osp:logoutput <dst> |

convenience for setting where status messages go; valid values for dst are cerr and cout |

--osp:erroroutput <dst> |

convenience for setting where error messages go; valid values for dst are cerr and cout |

--osp:device:<name> |

use name as the type of device for OSPRay to create; e.g. --osp:device:default gives you the default local device; Note if the device to be used is defined in a module, remember to pass --osp:module:<name> first |

--osp:setaffinity <n> |

if 1, bind software threads to hardware threads; 0 disables binding; default is 1 on KNL and 0 otherwise |

: Command line parameters accepted by OSPRay’s ospInit.

The second method of initialization is to explicitly create the device yourself, and possibly set parameters. This method looks almost identical to how other objects are created and used by OSPRay (described in later sections). The first step is to create the device with

OSPDevice ospNewDevice(const char *type);

where the type string maps to a specific device implementation. OSPRay

always provides the “default” device, which maps to a local CPU

rendering device. If it is enabled in the build, you can also use

“mpi” to access the MPI multi-node rendering device (see Parallel

Rendering with MPI section for more

information). Once a device is created, you can call

void ospDeviceSet1i(OSPDevice, const char *id, int val);

void ospDeviceSetString(OSPDevice, const char *id, const char *val);

void ospDeviceSetVoidPtr(OSPDevice, const char *id, void *val);

to set parameters on the device. The following parameters can be set on all devices:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| int | numThreads | number of threads which OSPRay should use |

| int | logLevel | logging level |

| string | logOutput | convenience for setting where status messages go; valid values are cerr and cout |

| string | errorOutput | convenience for setting where error messages go; valid values are cerr and cout |

| int | debug | set debug mode; equivalent to logLevel=2 and numThreads=1 |

| int | setAffinity | bind software threads to hardware threads if set to 1; 0 disables binding omitting the parameter will let OSPRay choose |

: Parameters shared by all devices.

Once parameters are set on the created device, the device must be committed with

void ospDeviceCommit(OSPDevice);

To use the newly committed device, you must call

void ospSetCurrentDevice(OSPDevice);

This then sets the given device as the object which will respond to all other OSPRay API calls.

Users can change parameters on the device after initialization (from either method above), by calling

OSPDevice ospGetCurrentDevice();

This function returns the handle to the device currently used to respond to OSPRay API calls, where users can set/change parameters and recommit the device. If changes are made to the device that is already set as the current device, it does not need to be set as current again.

Finally, OSPRay’s generic device parameters can be overridden via

environment variables for easy changes to OSPRay’s behavior without

needing to change the application (variables are prefixed by convention

with “OSPRAY_”):

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| OSPRAY_THREADS | equivalent to --osp:numthreads |

| OSPRAY_LOG_LEVEL | equivalent to --osp:loglevel |

| OSPRAY_LOG_OUTPUT | equivalent to --osp:logoutput |

| OSPRAY_ERROR_OUTPUT | equivalent to --osp:erroroutput |

| OSPRAY_DEBUG | equivalent to --osp:debug |

| OSPRAY_SET_AFFINITY | equivalent to --osp:setaffinity |

: Environment variables interpreted by OSPRay.

The following errors are currently used by OSPRay:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| OSP_NO_ERROR | no error occurred |

| OSP_UNKNOWN_ERROR | an unknown error occurred |

| OSP_INVALID_ARGUMENT | an invalid argument was specified |

| OSP_INVALID_OPERATION | the operation is not allowed for the specified object |

| OSP_OUT_OF_MEMORY | there is not enough memory to execute the command |

| OSP_UNSUPPORTED_CPU | the CPU is not supported (minimum ISA is SSE4.1) |

: Possible error codes, i.e. valid named constants of type OSPError.

These error codes are either directly return by some API functions, or are recorded to be later queried by the application via

OSPError ospDeviceGetLastErrorCode(OSPDevice);

A more descriptive error message can be queried by calling

const char* ospDeviceGetLastErrorMsg(OSPDevice);

Alternatively, the application can also register a callback function of type

typedef void (*OSPErrorFunc)(OSPError, const char* errorDetails);

via

void ospDeviceSetErrorFunc(OSPDevice, OSPErrorFunc);

to get notified when errors occur.

Applications may be interested in messages which OSPRay emits, whether for debugging or logging events. Applications can call

void ospDeviceSetStatusFunc(OSPDevice, OSPStatusFunc);

in order to register a callback function of type

typedef void (*OSPStatusFunc)(const char* messageText);

which OSPRay will use to emit status messages. By default, OSPRay uses a

callback which does nothing, so any output desired by an application

will require that a callback is provided. Note that callbacks for C++

std::cout and std::cerr can be alternatively set through ospInit()

or the OSPRAY_LOG_OUTPUT environment variable.

OSPRay’s functionality can be extended via plugins, which are

implemented in shared libraries. To load plugin name from

libospray_module_<name>.so (on Linux and Mac OS X) or

ospray_module_<name>.dll (on Windows) use

OSPError ospLoadModule(const char *name);

Modules are searched in OS-dependent paths. ospLoadModule returns

OSP_NO_ERROR if the plugin could be successfully loaded.

When the application is finished using OSPRay (typically on application exit), the OSPRay API should be finalized with

void ospShutdown();

This API call ensures that the current device is cleaned up

appropriately. Due to static object allocation having non-deterministic

ordering, it is recommended that applications call ospShutdown()

before the calling application process terminates.

All entities of OSPRay (the renderer, volumes, geometries, lights,

cameras, …) are a specialization of OSPObject and share common

mechanism to deal with parameters and lifetime.

An important aspect of object parameters is that parameters do not get passed to objects immediately. Instead, parameters are not visible at all to objects until they get explicitly committed to a given object via a call to

void ospCommit(OSPObject);

at which time all previously additions or changes to parameters are visible at the same time. If a user wants to change the state of an existing object (e.g., to change the origin of an already existing camera) it is perfectly valid to do so, as long as the changed parameters are recommitted.

The commit semantic allow for batching up multiple small changes, and specifies exactly when changes to objects will occur. This is important to ensure performance and consistency for devices crossing a PCI bus, or across a network. In our MPI implementation, for example, we can easily guarantee consistency among different nodes by MPI barrier’ing on every commit.

Note that OSPRay uses reference counting to manage the lifetime of all objects, so one cannot explicitly “delete” any object. Instead, to indicate that the application does not need and does not access the given object anymore, call

void ospRelease(OSPObject);

This decreases its reference count and if the count reaches 0 the

object will automatically get deleted. Passing NULL is not an error.

Parameters allow to configure the behavior of and to pass data to

objects. However, objects do not have an explicit interface for

reasons of high flexibility and a more stable compile-time API. Instead,

parameters are passed separately to objects in an arbitrary order, and

unknown parameters will simply be ignored. The following functions allow

adding various types of parameters with name id to a given object:

// add a C-string (zero-terminated char *) parameter

void ospSetString(OSPObject, const char *id, const char *s);

// add an object handle parameter to another object

void ospSetObject(OSPObject, const char *id, OSPObject object);

// add an untyped pointer -- this will *ONLY* work in local rendering!

void ospSetVoidPtr(OSPObject, const char *id, void *v);

// add scalar and vector integer and float parameters

void ospSetf (OSPObject, const char *id, float x);

void ospSet1f (OSPObject, const char *id, float x);

void ospSet1i (OSPObject, const char *id, int32_t x);

void ospSet2f (OSPObject, const char *id, float x, float y);

void ospSet2fv(OSPObject, const char *id, const float *xy);

void ospSet2i (OSPObject, const char *id, int x, int y);

void ospSet2iv(OSPObject, const char *id, const int *xy);

void ospSet3f (OSPObject, const char *id, float x, float y, float z);

void ospSet3fv(OSPObject, const char *id, const float *xyz);

void ospSet3i (OSPObject, const char *id, int x, int y, int z);

void ospSet3iv(OSPObject, const char *id, const int *xyz);

void ospSet4f (OSPObject, const char *id, float x, float y, float z, float w);

void ospSet4fv(OSPObject, const char *id, const float *xyzw);

// additional functions to pass vector integer and float parameters in C++

void ospSetVec2f(OSPObject, const char *id, const vec2f &v);

void ospSetVec2i(OSPObject, const char *id, const vec2i &v);

void ospSetVec3f(OSPObject, const char *id, const vec3f &v);

void ospSetVec3i(OSPObject, const char *id, const vec3i &v);

void ospSetVec4f(OSPObject, const char *id, const vec4f &v);

Users can also remove parameters that have been explicitly set via an ospSet call. Any parameters which have been removed will go back to their default value during the next commit unless a new parameter was set after the parameter was removed. The following API function removes the named parameter from the given object:

void ospRemoveParam(OSPObject, const char *id);

There is also the possibility to aggregate many values of the same type

into an array, which then itself can be used as a parameter to objects.

To create such a new data buffer, holding numItems elements of the

given type, from the initialization data pointed to by source and

optional creation flags, use

OSPData ospNewData(size_t numItems,

OSPDataType,

const void *source,

const uint32_t dataCreationFlags = 0);

The call returns an OSPData handle to the created array. The flag

OSP_DATA_SHARED_BUFFER indicates that the buffer can be shared with

the application. In this case the calling program guarantees that the

source pointer will remain valid for the duration that this data array

is being used. The enum type OSPDataType describes the different data

types that can be represented in OSPRay; valid constants are listed in

the table below.

| Type/Name | Description |

|---|---|

| OSP_DEVICE | API device object reference |

| OSP_VOID_PTR | void pointer |

| OSP_DATA | data reference |

| OSP_OBJECT | generic object reference |

| OSP_CAMERA | camera object reference |

| OSP_FRAMEBUFFER | framebuffer object reference |

| OSP_LIGHT | light object reference |

| OSP_MATERIAL | material object reference |

| OSP_TEXTURE | texture object reference |

| OSP_RENDERER | renderer object reference |

| OSP_MODEL | model object reference |

| OSP_GEOMETRY | geometry object reference |

| OSP_VOLUME | volume object reference |

| OSP_TRANSFER_FUNCTION | transfer function object reference |

| OSP_PIXEL_OP | pixel operation object reference |

| OSP_STRING | C-style zero-terminated character string |

| OSP_CHAR | 8 bit signed character scalar |

| OSP_UCHAR | 8 bit unsigned character scalar |

| OSP_UCHAR[234] | … and [234]-element vector |

| OSP_USHORT | 16 bit unsigned integer scalar |

| OSP_INT | 32 bit signed integer scalar |

| OSP_INT[234] | … and [234]-element vector |

| OSP_UINT | 32 bit unsigned integer scalar |

| OSP_UINT[234] | … and [234]-element vector |

| OSP_LONG | 64 bit signed integer scalar |

| OSP_LONG[234] | … and [234]-element vector |

| OSP_ULONG | 64 bit unsigned integer scalar |

| OSP_ULONG[234] | … and [234]-element vector |

| OSP_FLOAT | 32 bit single precision floating point scalar |

| OSP_FLOAT[234] | … and [234]-element vector |

| OSP_FLOAT3A | … and aligned 3-element vector |

| OSP_DOUBLE | 64 bit double precision floating point scalar |

: Valid named constants for OSPDataType.

To add a data array as parameter named id to another object call

void ospSetData(OSPObject, const char *id, OSPData);

Volumes are volumetric datasets with discretely sampled values in 3D

space, typically a 3D scalar field. To create a new volume object of

given type type use

OSPVolume ospNewVolume(const char *type);

The call returns NULL if that type of volume is not known by OSPRay,

or else an OSPVolume handle.

The common parameters understood by all volume variants are summarized in the table below.

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSPTransferFunction | transferFunction | transfer function to use | |

| vec2f | voxelRange | minimum and maximum of the scalar values | |

| bool | gradientShadingEnabled | false | volume is rendered with surface shading wrt. to normalized gradient |

| bool | preIntegration | false | use pre-integration for transfer function lookups |

| bool | singleShade | true | shade only at the point of maximum intensity |

| bool | adaptiveSampling | true | adapt ray step size based on opacity |

| float | adaptiveScalar | 15 | modifier for adaptive step size |

| float | adaptiveMaxSamplingRate | 2 | maximum sampling rate for adaptive sampling |

| float | samplingRate | 0.125 | sampling rate of the volume (this is the minimum step size for adaptive sampling) |

| vec3f | specular | gray 0.3 | specular color for shading |

| vec3f | volumeClippingBoxLower | disabled | lower coordinate (in object-space) to clip the volume values |

| vec3f | volumeClippingBoxUpper | disabled | upper coordinate (in object-space) to clip the volume values |

: Configuration parameters shared by all volume types.

Note that if voxelRange is not provided for a volume then OSPRay will

compute it based on the voxel data, which may result in slower data

updates.

Structured volumes only need to store the values of the samples, because their addresses in memory can be easily computed from a 3D position. A common type of structured volumes are regular grids. OSPRay supports two variants that differ in how the volumetric data for the regular grids is specified.

The first variant shares the voxel data with the application. Such a

volume type is created by passing the type string

“shared_structured_volume” to ospNewVolume. The voxel data is laid

out in memory in XYZ order and provided to the volume via a

data buffer parameter named “voxelData”.

The second regular grid variant is optimized for rendering performance:

data locality in memory is increased by arranging the voxel data in

smaller blocks. This volume type is created by passing the type string

“block_bricked_volume” to ospNewVolume. Because of this

rearrangement of voxel data it cannot be shared the with the application

anymore, but has to be transferred to OSPRay via

OSPError ospSetRegion(OSPVolume, void *source,

const vec3i ®ionCoords,

const vec3i ®ionSize);

The voxel data pointed to by source is copied into the given volume

starting at position regionCoords, must be of size regionSize and be

placed in memory in XYZ order. Note that OSPRay distinguishes between

volume data and volume parameters. This function must be called only

after all volume parameters (in particular dimensions and voxelType,

see below) have been set and before ospCommit(volume) is called. If

necessary then memory for the volume is allocated on the first call to

this function.

The common parameters understood by both structured volume variants are summarized in the table below.

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3i | dimensions | number of voxels in each dimension (x, y, z) | |

| string | voxelType | data type of each voxel, currently supported are: | |

| “uchar” (8 bit unsigned integer) | |||

| “short” (16 bit signed integer) | |||

| “ushort” (16 bit unsigned integer) | |||

| “float” (32 bit single precision floating point) | |||

| “double” (64 bit double precision floating point) | |||

| vec3f | gridOrigin | (0, 0, 0) | origin of the grid in world-space |

| vec3f | gridSpacing | (1, 1, 1) | size of the grid cells in world-space |

: Additional configuration parameters for structured volumes.

AMR volumes are specified as a list of bricks, which are levels of

refinement in potentially overlapping regions. There can be any number

of refinement levels and any number of bricks at any level of

refinement. An AMR volume type is created by passing the type string

“amr_volume” to ospNewVolume.

Applications should first create an OSPData array which holds

information about each brick. The following structure is used to

populate this array (found in ospray.h):

struct amr_brick_info

{

box3i bounds;

int refinementLevel;

float cellWidth;

};

Then for each brick, the application should create an OSPData array of

OSPData handles, where each handle is the data per-brick. Currently we

only support float voxels.

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3f | gridOrigin | (0, 0, 0) | origin of the grid in world-space |

| vec3f | gridSpacing | (1, 1, 1) | size of the grid cells in world-space |

| string | amrMethod | current | sampling method; valid values are “finest”, “current”, or “octant” |

| string | voxelType | undefined | data type of each voxel, currently supported are: |

| “uchar” (8 bit unsigned integer) | |||

| “short” (16 bit signed integer) | |||

| “ushort” (16 bit unsigned integer) | |||

| “float” (32 bit single precision floating point) | |||

| “double” (64 bit double precision floating point) | |||

| OSPData | brickInfo | array of info defining each brick | |

| OSPData | brickData | array of handles to per-brick voxel data |

: Additional configuration parameters for AMR volumes.

Lastly, note that the gridOrigin and gridSpacing parameters act just

like the structured volume equivalent, but they only modify the root

(coarsest level) of refinement.

Unstructured volumes can contain tetrahedral, wedge, or hexahedral cell

types, and are defined by three arrays: vertices, corresponding field

values, and eight indices per cell (first four are -1 for tetrahedral

cells, first two are -2 for wedge cells). An unstructured volume type is

created by passing the type string “unstructured_volume” to

ospNewVolume.

Field values can be specified per-vertex (field) or per-cell

(cellField). If both values are set, cellField takes precedence.

Similar to triangle mesh, each tetrahedron is formed by a group of indices into the vertices. For each vertex, the corresponding (by array index) data value will be used for sampling when rendering. Note that the index order for each tetrahedron does not matter, as OSPRay internally calculates vertex normals to ensure proper sampling and interpolation.

For wedge cells, each wedge is formed by a group of six indices into the

vertices and data value. Vertex ordering is the same as VTK_WEDGE -

three bottom vertices counterclockwise, then top three counterclockwise.

For hexahedral cells, each hexahedron is formed by a group of eight

indices into the vertices and data value. Vertex ordering is the same as

VTK_HEXAHEDRON – four bottom vertices counterclockwise, then top four

counterclockwise.

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3f[] | vertices | data array of vertex positions | |

| float[] | field | data array of vertex data values to be sampled | |

| float[] | cellField | data array of cell data values to be sampled | |

| vec4i[] | indices | data array of tetrahedra indices (into vertices and field) | |

| string | hexMethod | planar | “planar” (faster, assumes planar sides) or “nonplanar” |

| bool | precomputedNormals | true | whether to accelerate by precomputing, at a cost of 72 bytes/cell |

: Additional configuration parameters for unstructured volumes.

Transfer functions map the scalar values of volumes to color and opacity

and thus they can be used to visually emphasize certain features of the

volume. To create a new transfer function of given type type use

OSPTransferFunction ospNewTransferFunction(const char *type);

The call returns NULL if that type of transfer functions is not known

by OSPRay, or else an OSPTransferFunction handle to the created

transfer function. That handle can be assigned to a volume as parameter

“transferFunction” using ospSetObject.

One type of transfer function that is built-in in OSPRay is the linear

transfer function, which interpolates between given equidistant colors

and opacities. It is create by passing the string “piecewise_linear”

to ospNewTransferFunction and it is controlled by these parameters:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec3f[] | colors | data array of RGB colors |

| float[] | opacities | data array of opacities |

| vec2f | valueRange | domain (scalar range) this function maps from |

: Parameters accepted by the linear transfer function.

Geometries in OSPRay are objects that describe surfaces. To create a new

geometry object of given type type use

OSPGeometry ospNewGeometry(const char *type);

The call returns NULL if that type of geometry is not known by OSPRay,

or else an OSPGeometry handle.

A traditional triangle mesh (indexed face set) geometry is created by

calling ospNewGeometry with type string “triangles”. Once created, a

triangle mesh recognizes the following parameters:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec3f(a)[] | vertex | data array of vertex positions |

| vec3f(a)[] | vertex.normal | data array of vertex normals |

| vec4f[] / vec3fa[] | vertex.color | data array of vertex colors (RGBA/RGB) |

| vec2f[] | vertex.texcoord | data array of vertex texture coordinates |

| vec3i(a)[] | index | data array of triangle indices (into the vertex array(s)) |

: Parameters defining a triangle mesh geometry.

The vertex and index arrays are mandatory to create a valid triangle

mesh.

A mesh consisting of quads is created by calling ospNewGeometry with

type string “quads”. Once created, a quad mesh recognizes the

following parameters:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec3f(a)[] | vertex | data array of vertex positions |

| vec3f(a)[] | vertex.normal | data array of vertex normals |

| vec4f[] / vec3fa[] | vertex.color | data array of vertex colors (RGBA/RGB) |

| vec2f[] | vertex.texcoord | data array of vertex texture coordinates |

| vec4i[] | index | data array of quad indices (into the vertex array(s)) |

: Parameters defining a quad mesh geometry.

The vertex and index arrays are mandatory to create a valid quad

mesh. A quad is internally handled as a pair of two triangles, thus

mixing triangles and quad is supported by encoding a triangle as a quad

with the last two vertex indices being identical (w=z).

A geometry consisting of individual spheres, each of which can have an

own radius, is created by calling ospNewGeometry with type string

“spheres”. The spheres will not be tessellated but rendered

procedurally and are thus perfectly round. To allow a variety of sphere

representations in the application this geometry allows a flexible way

of specifying the data of center position and radius within a

data array:

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| float | radius | 0.01 | radius of all spheres (if offset_radius is not used) |

| OSPData | spheres | NULL | memory holding the spatial data of all spheres |

| int | bytes_per_sphere | 16 | size (in bytes) of each sphere within the spheres array |

| int | offset_center | 0 | offset (in bytes) of each sphere’s “vec3f center” position (in object-space) within the spheres array |

| int | offset_radius | -1 | offset (in bytes) of each sphere’s “float radius” within the spheres array (-1 means disabled and use radius) |

| int | offset_colorID | -1 | offset (in bytes) of each sphere’s “int colorID” within the spheres array (-1 means disabled and use the shared material color) |

| vec4f[] / vec3f(a)[] / vec4uc | color | NULL | data array of colors (RGBA/RGB), color is constant for each sphere |

| int | color_offset | 0 | offset (in bytes) to the start of the color data in color |

| int | color_format | color.data_type |

the format of the color data. Can be one of: OSP_FLOAT4, OSP_FLOAT3, OSP_FLOAT3A or OSP_UCHAR4. Defaults to the type of data in color |

| int | color_stride | sizeof(color_format) |

stride (in bytes) between each color element in the color array. Defaults to the size of a single element of type color_format |

| vec2f[] | texcoord | NULL | data array of texture coordinates, coordinate is constant for each sphere |

: Parameters defining a spheres geometry.

A geometry consisting of individual cylinders, each of which can have an

own radius, is created by calling ospNewGeometry with type string

“cylinders”. The cylinders will not be tessellated but rendered

procedurally and are thus perfectly round. To allow a variety of

cylinder representations in the application this geometry allows a

flexible way of specifying the data of offsets for start position, end

position and radius within a data array. All parameters are

listed in the table below.

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| float | radius | 0.01 | radius of all cylinders (if offset_radius is not used) |

| OSPData | cylinders | NULL | memory holding the spatial data of all cylinders |

| int | bytes_per_cylinder | 24 | size (in bytes) of each cylinder within the cylinders array |

| int | offset_v0 | 0 | offset (in bytes) of each cylinder’s “vec3f v0” position (the start vertex, in object-space) within the cylinders array |

| int | offset_v1 | 12 | offset (in bytes) of each cylinder’s “vec3f v1” position (the end vertex, in object-space) within the cylinders array |

| int | offset_radius | -1 | offset (in bytes) of each cylinder’s “float radius” within the cylinders array (-1 means disabled and use radius instead) |

| vec4f[] / vec3f(a)[] | color | NULL | data array of colors (RGBA/RGB), color is constant for each cylinder |

| OSPData | texcoord | NULL | data array of texture coordinates, in pairs (each a vec2f at vertex v0 and v1) |

: Parameters defining a cylinders geometry.

For texturing each cylinder is seen as a 1D primitive, i.e. a line segment: the 2D texture coordinates at its vertices v0 and v1 are linearly interpolated.

A geometry consisting of multiple streamlines is created by calling

ospNewGeometry with type string “streamlines”. The streamlines are

internally assembled either from connected (and rounded) cylinder

segments, or represented as Bézier curves; they are thus always

perfectly round. The parameters defining this geometry are listed in the

table below.

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| float | radius | global radius of all streamlines (if per-vertex radius is not used), default 0.01 |

| bool | smooth | enable curve interpolation, default off (always on if per-vertex radius is used) |

| vec3fa[] / vec4f[] | vertex | data array of all vertex position (and optional radius) for all streamlines |

| vec4f[] | vertex.color | data array of corresponding vertex colors (RGBA) |

| float[] | vertex.radius | data array of corresponding vertex radius |

| int32[] | index | data array of indices to the first vertex of a link |

: Parameters defining a streamlines geometry.

Each streamline is specified by a set of (aligned) control points in

vertex. If smooth is disabled and a constant radius is used for

all streamlines then all vertices belonging to to the same logical

streamline are connected via cylinders, with additional

spheres at each vertex to create a continuous, closed

surface. Otherwise, streamlines are represented as Bézier curves,

smoothly interpolating the vertices. This mode supports per-vertex

varying radii (either given in vertex.radius, or in the 4th component

of a vec4f vertex), but is slower and consumes more memory. Also,

the radius needs to be smaller than the curvature radius of the Bézier

curve at each location on the curve.

A streamlines geometry can contain multiple disjoint streamlines, each

streamline is specified as a list of segments (or links) referenced via

index: each entry e of the index array points the first vertex of

a link (vertex[index[e]]) and the second vertex of the link is

implicitly the directly following one (vertex[index[e]+1]). For

example, two streamlines of vertices (A-B-C-D) and (E-F-G),

respectively, would internally correspond to five links (A-B, B-C,

C-D, E-F, and F-G), and would be specified via an array of

vertices [A,B,C,D,E,F,G], plus an array of link indices [0,1,2,4,5].

A geometry consisting of multiple curves is created by calling

ospNewGeometry with type string “curves”. The parameters defining

this geometry are listed in the table below.

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| string | curveType | “flat” (ray oriented), “round” (circular cross section), “ribbon” (normal oriented flat curve) |

| string | curveBasis | “linear”, “bezier”, “bspline”, “hermite” |

| vec4f[] | vertex | data array of vertex position and radius |

| int32[] | index | data array of indices to the first vertex or tangent of a curve segment |

| vec3f[] | vertex.normal | data array of curve normals (only for “ribbon” curves) |

| vec3f[] | vertex.tangent | data array of curve tangents (only for “hermite” curves) |

: Parameters defining a curves geometry.

See Embree documentation for discussion of curve types and data formatting.

OSPRay can directly render multiple isosurfaces of a volume without

first tessellating them. To do so create an isosurfaces geometry by

calling ospNewGeometry with type string “isosurfaces”. Each

isosurface will be colored according to the provided volume’s transfer

function.

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| float[] | isovalues | data array of isovalues |

| OSPVolume | volume | handle of the volume to be isosurfaced |

: Parameters defining an isosurfaces geometry.

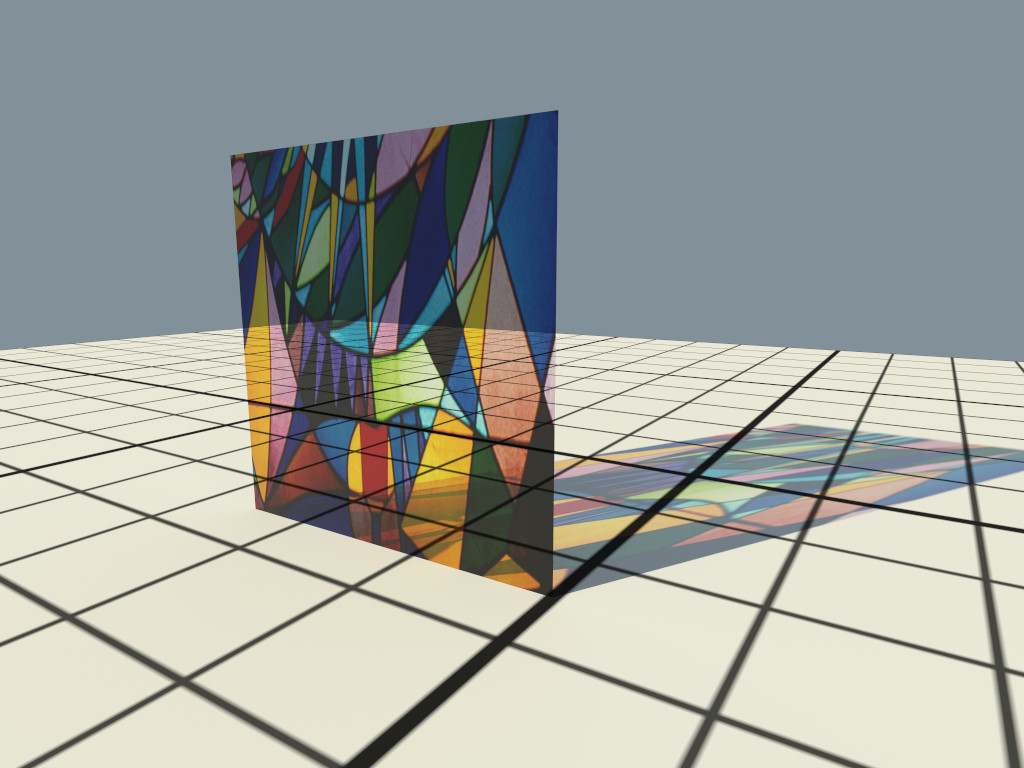

One tool to highlight interesting features of volumetric data is to

visualize 2D cuts (or slices) by placing planes into the volume. Such a

slices geometry is created by calling ospNewGeometry with type string

“slices”. The planes are defined by the coefficients

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec4f[] | planes | data array with plane coefficients for all slices |

| OSPVolume | volume | handle of the volume that will be sliced |

: Parameters defining a slices geometry.

OSPRay supports instancing via a special type of geometry. Instances are

created by transforming another given model

modelToInstantiate with the given affine transformation transform by

calling

OSPGeometry ospNewInstance(OSPModel modelToInstantiate, const affine3f &transform);

A renderer is the central object for rendering in OSPRay. Different

renderers implement different features and support different materials.

To create a new renderer of given type type use

OSPRenderer ospNewRenderer(const char *type);

The call returns NULL if that type of renderer is not known, or else

an OSPRenderer handle to the created renderer. General parameters of

all renderers are

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSPModel | model | the model to render | |

| OSPCamera | camera | the camera to be used for rendering | |

| OSPLight[] | lights | data array with handles of the lights | |

| float | epsilon | 10-6 | ray epsilon to avoid self-intersections, relative to scene diameter |

| int | spp | 1 | samples per pixel |

| int | maxDepth | 20 | maximum ray recursion depth |

| float | minContribution | 0.001 | sample contributions below this value will be neglected to speed-up rendering |

| float | varianceThreshold | 0 | threshold for adaptive accumulation |

: Parameters understood by all renderers.

OSPRay’s renderers support a feature called adaptive accumulation, which

accelerates progressive rendering by stopping the

rendering and refinement of image regions that have an estimated

variance below the varianceThreshold. This feature requires a

framebuffer with an OSP_FB_VARIANCE channel.

The SciVis renderer is a fast ray tracer for scientific visualization

which supports volume rendering and ambient occlusion (AO). It is

created by passing the type string “scivis” or “raytracer” to

ospNewRenderer. In addition to the general parameters

understood by all renderers the SciVis renderer supports the following

special parameters:

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| bool | shadowsEnabled | false | whether to compute (hard) shadows |

| int | aoSamples | 0 | number of rays per sample to compute ambient occlusion |

| float | aoDistance | 1020 | maximum distance to consider for ambient occlusion |

| bool | aoTransparencyEnabled | false | whether object transparency is respected when computing ambient occlusion (slower) |

| bool | oneSidedLighting | true | if true back-facing surfaces (wrt. light source) receive no illumination |

| float / vec3f / vec4f | bgColor | black, transparent | background color and alpha (RGBA) |

| OSPTexture | maxDepthTexture | NULL | screen-sized float texture with maximum far distance per pixel (use texture type ‘texture2d’) |

: Special parameters understood by the SciVis renderer.

Note that the intensity (and color) of AO is controlled via an ambient

light. If aoSamples is zero (the default) then

ambient lights cause ambient illumination (without occlusion).

Per default the background of the rendered image will be transparent

black, i.e. the alpha channel holds the opacity of the rendered objects.

This facilitates transparency-aware blending of the image with an

arbitrary background image by the application. The parameter bgColor

can be used to already blend with a constant background color (and

alpha) during rendering.

The SciVis renderer supports depth composition with images of other

renderers, for example to incorporate help geometries of a 3D UI that

were rendered with OpenGL. The screen-sized texture

maxDepthTexture must have format OSP_TEXTURE_R32F and flag

OSP_TEXTURE_FILTER_NEAREST. The fetched values are used to limit the

distance of primary rays, thus objects of other renderers can hide

objects rendered by OSPRay.

The path tracer supports soft shadows, indirect illumination and

realistic materials. This renderer is created by passing the type string

“pathtracer” to ospNewRenderer. In addition to the general

parameters understood by all renderers the path tracer

supports the following special parameters:

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| int | rouletteDepth | 5 | ray recursion depth at which to start Russian roulette termination |

| float | maxContribution | ∞ | samples are clamped to this value before they are accumulated into the framebuffer |

| OSPTexture | backplate | NULL | texture image used as background, replacing visible lights in infinity (e.g. the HDRI light) |

: Special parameters understood by the path tracer.

The path tracer requires that materials are assigned to geometries, otherwise surfaces are treated as completely black.

Models are a container of scene data. They can hold the different geometries and volumes as well as references to (and instances of) other models. A model is associated with a single logical acceleration structure. To create an (empty) model call

OSPModel ospNewModel();

The call returns an OSPModel handle to the created model. To add an

already created geometry or volume to a model use

void ospAddGeometry(OSPModel, OSPGeometry);

void ospAddVolume(OSPModel, OSPVolume);

An existing geometry or volume can be removed from a model with

void ospRemoveGeometry(OSPModel, OSPGeometry);

void ospRemoveVolume(OSPModel, OSPVolume);

Finally, Models can be configured with parameters for making various feature/performance trade-offs:

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| bool | dynamicScene | false | use RTC_SCENE_DYNAMIC flag (faster BVH build, slower ray traversal), otherwise uses RTC_SCENE_STATIC flag (faster ray traversal, slightly slower BVH build) |

| bool | compactMode | false | tell Embree to use a more compact BVH in memory by trading ray traversal performance |

| bool | robustMode | false | tell Embree to enable more robust ray intersection code paths (slightly slower) |

: Parameters understood by Models

To create a new light source of given type type use

OSPLight ospNewLight3(const char *type);

The call returns NULL if that type of light is not known by the

renderer, or else an OSPLight handle to the created light source. All

light sources2 accept the following parameters:

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3f(a) | color | white | color of the light |

| float | intensity | 1 | intensity of the light (a factor) |

| bool | isVisible | true | whether the light can be directly seen |

: Parameters accepted by the all lights.

The following light types are supported by most OSPRay renderers.

The distant light (or traditionally the directional light) is thought to

be very far away (outside of the scene), thus its light arrives (almost)

as parallel rays. It is created by passing the type string “distant”

to ospNewLight3. In addition to the general parameters

understood by all lights the distant light supports the following

special parameters:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec3f(a) | direction | main emission direction of the distant light |

| float | angularDiameter | apparent size (angle in degree) of the light |

: Special parameters accepted by the distant light.

Setting the angular diameter to a value greater than zero will result in soft shadows when the renderer uses stochastic sampling (like the path tracer). For instance, the apparent size of the sun is about 0.53°.

The sphere light (or the special case point light) is a light emitting

uniformly in all directions. It is created by passing the type string

“sphere” to ospNewLight3. In addition to the general

parameters understood by all lights the sphere light supports

the following special parameters:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec3f(a) | position | the center of the sphere light, in world-space |

| float | radius | the size of the sphere light |

: Special parameters accepted by the sphere light.

Setting the radius to a value greater than zero will result in soft shadows when the renderer uses stochastic sampling (like the path tracer).

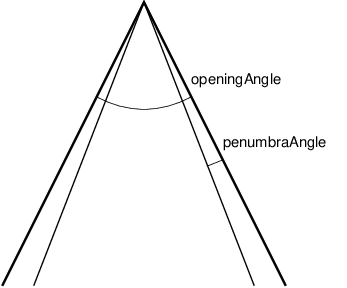

The spot light is a light emitting into a cone of directions. It is

created by passing the type string “spot” to ospNewLight3. In

addition to the general parameters understood by all lights

the spot light supports the special parameters listed in the table.

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec3f(a) | position | the center of the spot light, in world-space |

| vec3f(a) | direction | main emission direction of the spot |

| float | openingAngle | full opening angle (in degree) of the spot; outside of this cone is no illumination |

| float | penumbraAngle | size (angle in degree) of the “penumbra”, the region between the rim (of the illumination cone) and full intensity of the spot; should be smaller than half of openingAngle |

| float | radius | the size of the spot light, the radius of a disk with normal direction |

: Special parameters accepted by the spot light.

Setting the radius to a value greater than zero will result in soft shadows when the renderer uses stochastic sampling (like the path tracer).

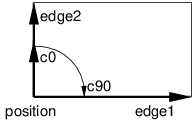

The quad3 light is a planar, procedural area light source emitting

uniformly on one side into the half space. It is created by passing the

type string “quad” to ospNewLight3. In addition to the general

parameters understood by all lights the spot light supports

the following special parameters:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec3f(a) | position | world-space position of one vertex of the quad light |

| vec3f(a) | edge1 | vector to one adjacent vertex |

| vec3f(a) | edge2 | vector to the other adjacent vertex |

: Special parameters accepted by the quad light.

The emission side is determined by the cross product of edge1×edge2.

Note that only renderers that use stochastic sampling (like the path

tracer) will compute soft shadows from the quad light. Other renderers

will just sample the center of the quad light, which results in hard

shadows.

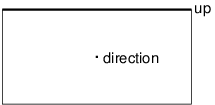

The HDRI light is a textured light source surrounding the scene and

illuminating it from infinity. It is created by passing the type string

“hdri” to ospNewLight3. In addition to the parameter

intensity the HDRI light supports the following special

parameters:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec3f(a) | up | up direction of the light in world-space |

| vec3f(a) | dir | direction to which the center of the texture will be mapped to (analog to panoramic camera) |

| OSPTexture | map | environment map in latitude / longitude format |

: Special parameters accepted by the HDRI light.

Note that the currently only the path tracer supports the HDRI light.

The ambient light surrounds the scene and illuminates it from infinity

with constant radiance (determined by combining the parameters color

and intensity). It is created by passing the type string

“ambient” to ospNewLight3.

Note that the SciVis renderer uses ambient lights to control the color and intensity of the computed ambient occlusion (AO).

The path tracer will consider illumination by geometries which have a light emitting material assigned (for example the Luminous material).

Materials describe how light interacts with surfaces, they give objects

their distinctive look. To let the given renderer create a new material

of given type type call

OSPMaterial ospNewMaterial2(const char *renderer_type, const char *material_type);

The call returns NULL if the material type is not known by the

renderer type, or else an OSPMaterial handle to the created material.

The handle can then be used to assign the material to a given geometry

with

void ospSetMaterial(OSPGeometry, OSPMaterial);

The OBJ material is the workhorse material supported by both the SciVis

renderer and the path tracer. It

offers widely used common properties like diffuse and specular

reflection and is based on the MTL material

format of Lightwave’s OBJ scene

files. To create an OBJ material pass the type string “OBJMaterial” to

ospNewMaterial2. Its main parameters are

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3f | Kd | white 0.8 | diffuse color |

| vec3f | Ks | black | specular color |

| float | Ns | 10 | shininess (Phong exponent), usually in [2–10^4^] |

| float | d | opaque | opacity |

| vec3f | Tf | black | transparency filter color |

| OSPTexture | map_Bump | NULL | normal map |

: Main parameters of the OBJ material.

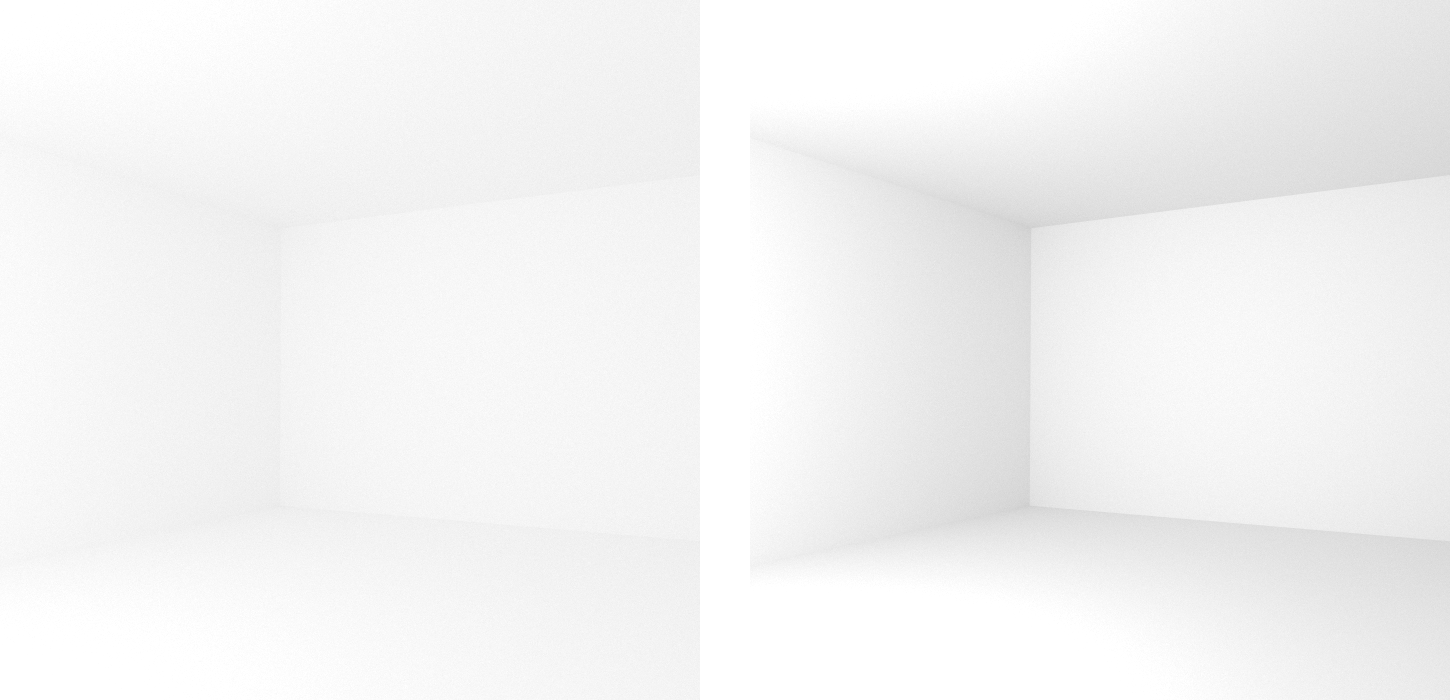

In particular when using the path tracer it is important to adhere to

the principle of energy conservation, i.e. that the amount of light

reflected by a surface is not larger than the light arriving. Therefore

the path tracer issues a warning and renormalizes the color parameters

if the sum of Kd, Ks, and Tf is larger than one in any color

channel. Similarly important to mention is that almost all materials of

the real world reflect at most only about 80% of the incoming light. So

even for a white sheet of paper or white wall paint do better not set

Kd larger than 0.8; otherwise rendering times are unnecessary long and

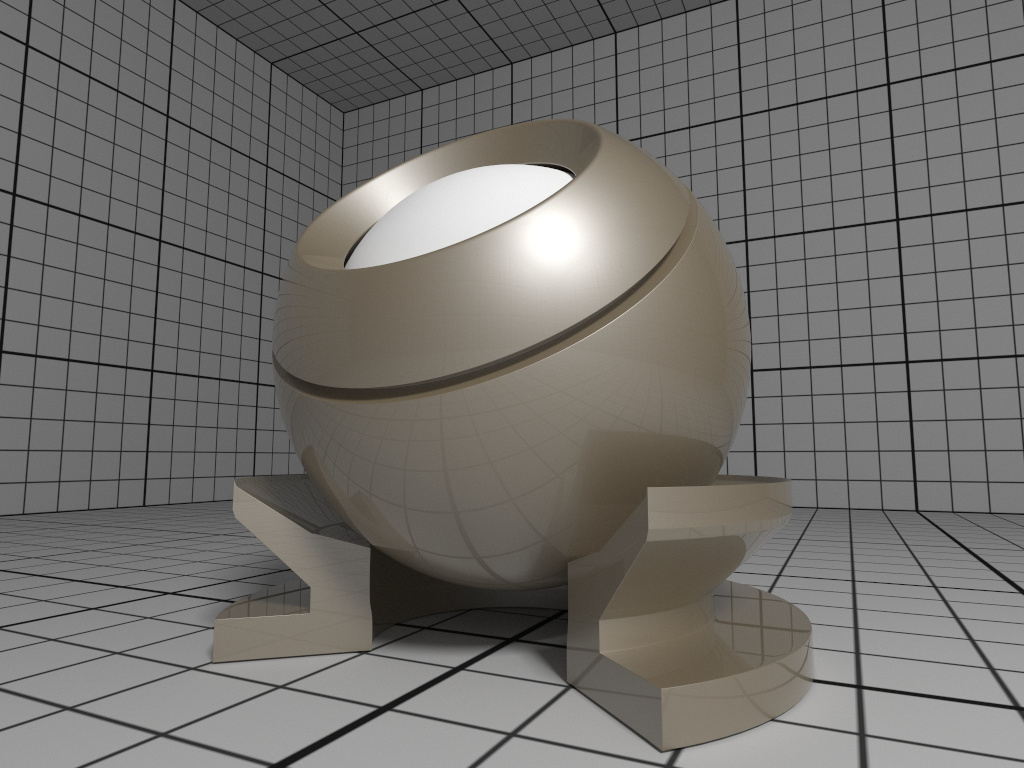

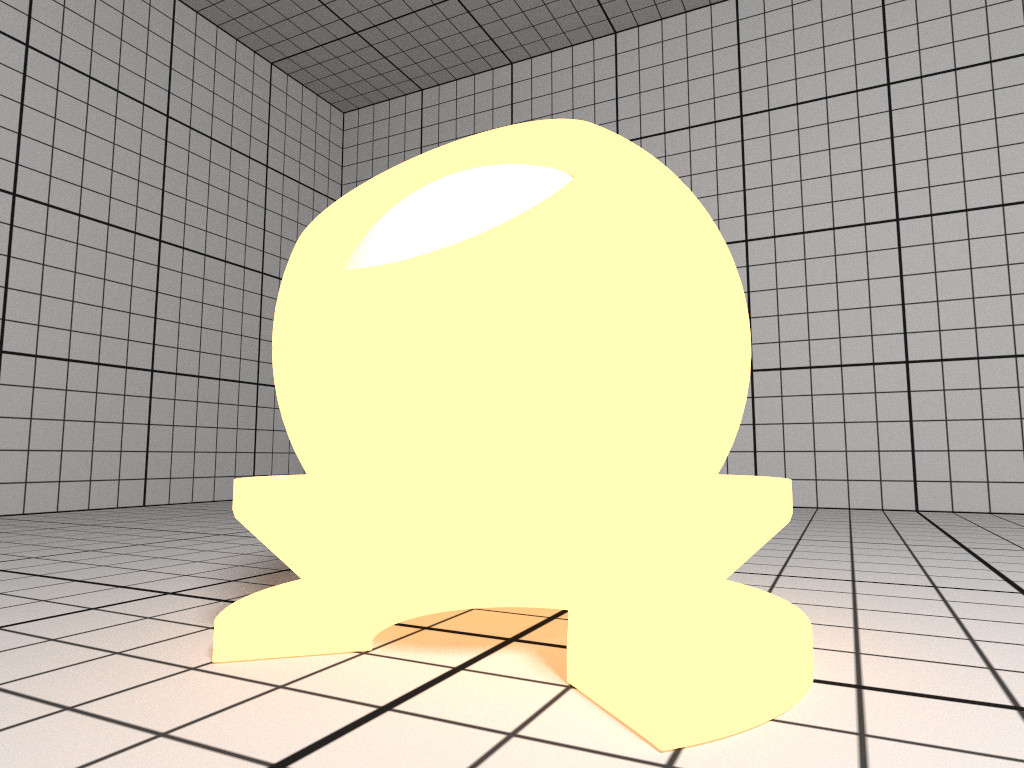

the contrast in the final images is low (for example, the corners of a

white room would hardly be discernible, as can be seen in the figure

below).

Note that currently only the path tracer implements colored transparency

with Tf.

Normal mapping can simulate small geometric features via the texture

map_Bump. The normals

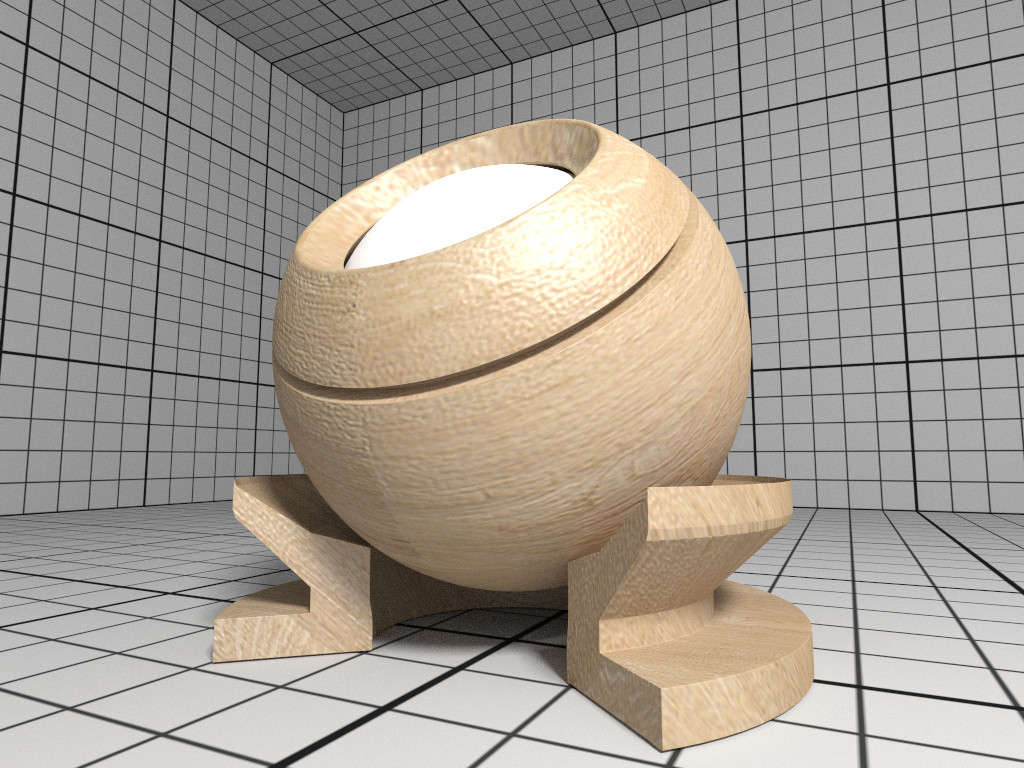

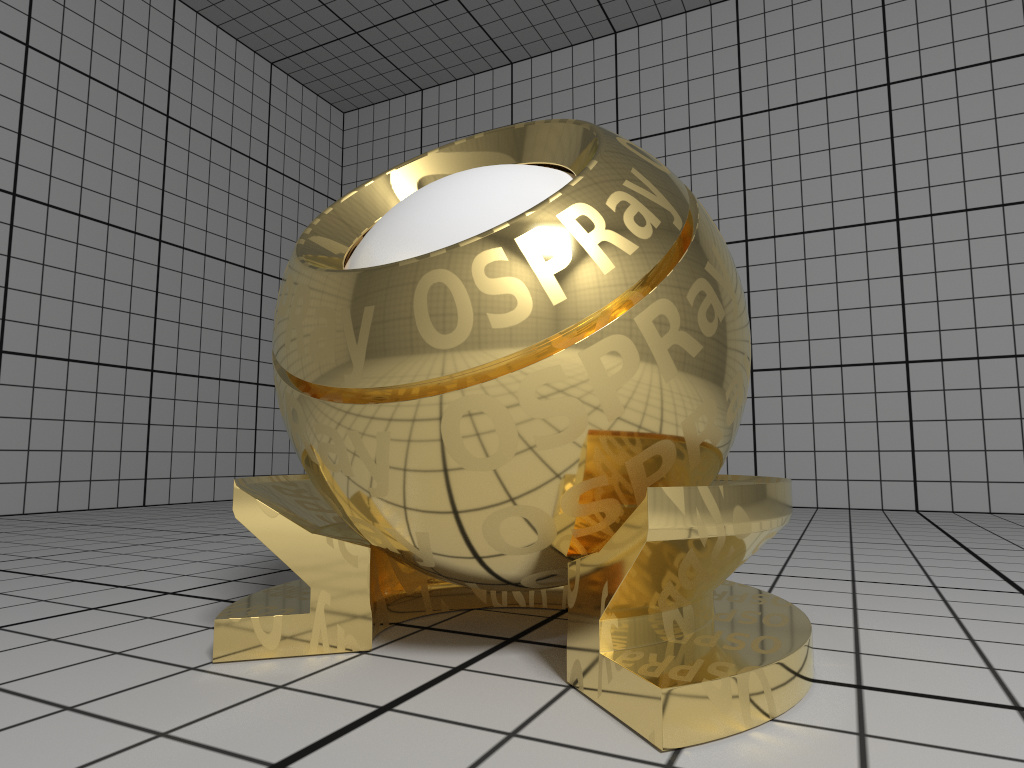

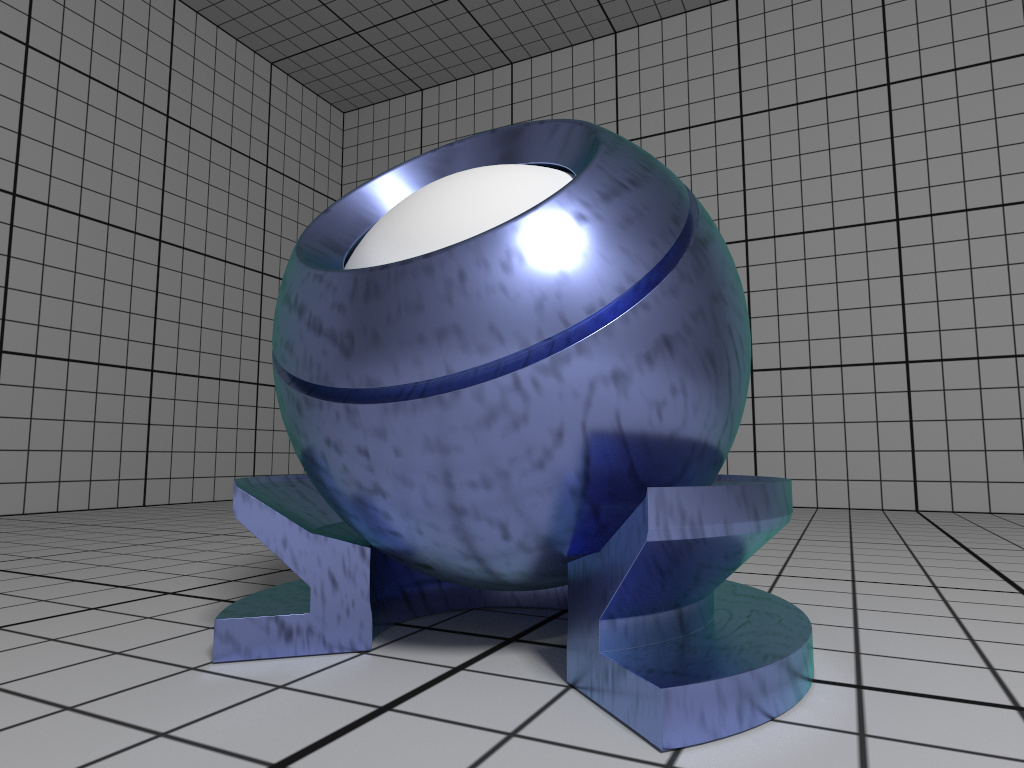

The Principled material is the most complex material offered by the

path tracer, which is capable of producing a wide

variety of materials (e.g., plastic, metal, wood, glass) by combining

multiple different layers and lobes. It uses the GGX microfacet

distribution with approximate multiple scattering for dielectrics and

metals, uses the Oren-Nayar model for diffuse reflection, and is energy

conserving. To create a Principled material, pass the type string

“Principled” to ospNewMaterial2. Its parameters are listed in the

table below.

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3f | baseColor | white 0.8 | base reflectivity (diffuse and/or metallic) |

| vec3f | edgeColor | white | edge tint (metallic only) |

| float | metallic | 0 | mix between dielectric (diffuse and/or specular) and metallic (specular only with complex IOR) in [0–1] |

| float | diffuse | 1 | diffuse reflection weight in [0–1] |

| float | specular | 1 | specular reflection/transmission weight in [0–1] |

| float | ior | 1 | dielectric index of refraction |

| float | transmission | 0 | specular transmission weight in [0–1] |

| vec3f | transmissionColor | white | attenuated color due to transmission (Beer’s law) |

| float | transmissionDepth | 1 | distance at which color attenuation is equal to transmissionColor |

| float | roughness | 0 | diffuse and specular roughness in [0–1], 0 is perfectly smooth |

| float | anisotropy | 0 | amount of specular anisotropy in [0–1] |

| float | rotation | 0 | rotation of the direction of anisotropy in [0–1], 1 is going full circle |

| float | normal | 1 | default normal map/scale for all layers |

| float | baseNormal | 1 | base normal map/scale (overrides default normal) |

| bool | thin | false | flag specifying whether the material is thin or solid |

| float | thickness | 1 | thickness of the material (thin only), affects the amount of color attenuation due to specular transmission |

| float | backlight | 0 | amount of diffuse transmission (thin only) in [0–2], 1 is 50% reflection and 50% transmission, 2 is transmission only |

| float | coat | 0 | clear coat layer weight in [0–1] |

| float | coatIor | 1.5 | clear coat index of refraction |

| vec3f | coatColor | white | clear coat color tint |

| float | coatThickness | 1 | clear coat thickness, affects the amount of color attenuation |

| float | coatRoughness | 0 | clear coat roughness in [0–1], 0 is perfectly smooth |

| float | coatNormal | 1 | clear coat normal map/scale (overrides default normal) |

| float | sheen | 0 | sheen layer weight in [0–1] |

| vec3f | sheenColor | white | sheen color tint |

| float | sheenTint | 0 | how much sheen is tinted from sheenColor towards baseColor |

| float | sheenRoughness | 0.2 | sheen roughness in [0–1], 0 is perfectly smooth |

| float | opacity | 1 | cut-out opacity/transparency, 1 is fully opaque |

: Parameters of the Principled material.

All parameters can be textured by passing a texture handle,

suffixed with “Map” (e.g., “baseColorMap”); [texture

transformations] are supported as well.

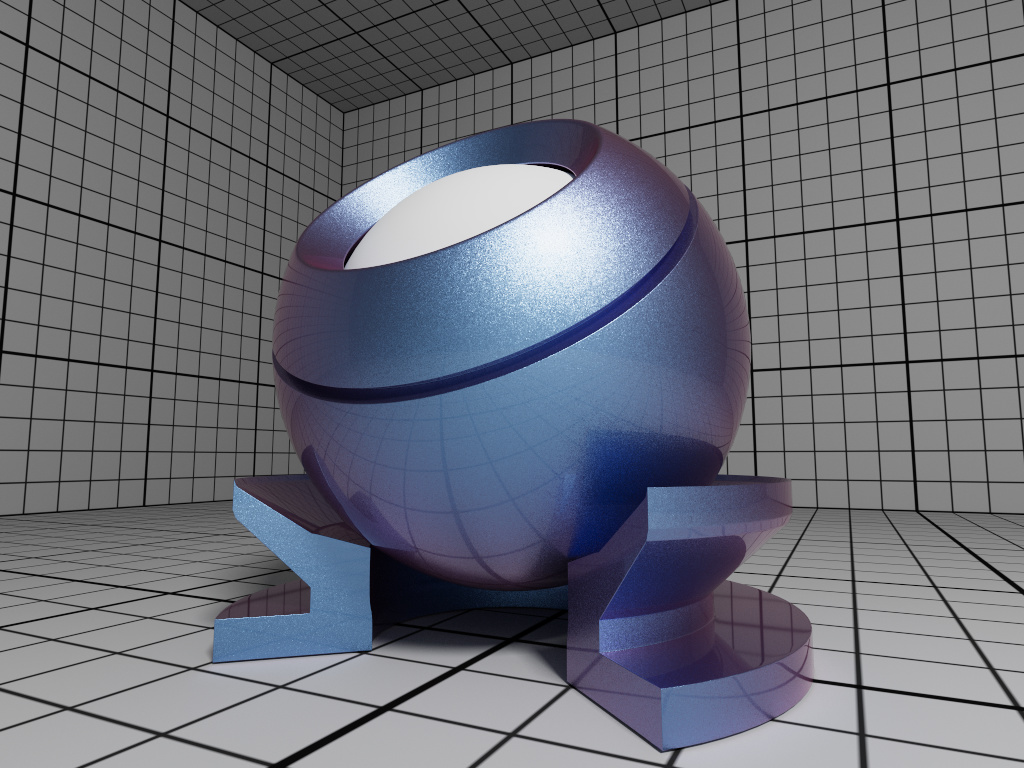

The CarPaint material is a specialized version of the Principled

material for rendering different types of car paints. To create a

CarPaint material, pass the type string “CarPaint” to

ospNewMaterial2. Its parameters are listed in the table below.

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3f | baseColor | white 0.8 | diffuse base reflectivity |

| float | roughness | 0 | diffuse roughness in [0–1], 0 is perfectly smooth |

| float | normal | 1 | normal map/scale |

| float | flakeDensity | 0 | density of metallic flakes in [0–1], 0 disables flakes, 1 fully covers the surface with flakes |

| float | flakeScale | 100 | scale of the flake structure, higher values increase the amount of flakes |

| float | flakeSpread | 0.3 | flake spread in [0–1] |

| float | flakeJitter | 0.75 | flake randomness in [0–1] |

| float | flakeRoughness | 0.3 | flake roughness in [0–1], 0 is perfectly smooth |

| float | coat | 1 | clear coat layer weight in [0–1] |

| float | coatIor | 1.5 | clear coat index of refraction |

| vec3f | coatColor | white | clear coat color tint |

| float | coatThickness | 1 | clear coat thickness, affects the amount of color attenuation |

| float | coatRoughness | 0 | clear coat roughness in [0–1], 0 is perfectly smooth |

| float | coatNormal | 1 | clear coat normal map/scale |

| vec3f | flipflopColor | white | reflectivity of coated flakes at grazing angle, used together with coatColor produces a pearlescent paint |

| float | flipflopFalloff | 1 | flip flop color falloff, 1 disables the flip flop effect |

: Parameters of the CarPaint material.

All parameters can be textured by passing a texture handle,

suffixed with “Map” (e.g., “baseColorMap”); [texture

transformations] are supported as well.

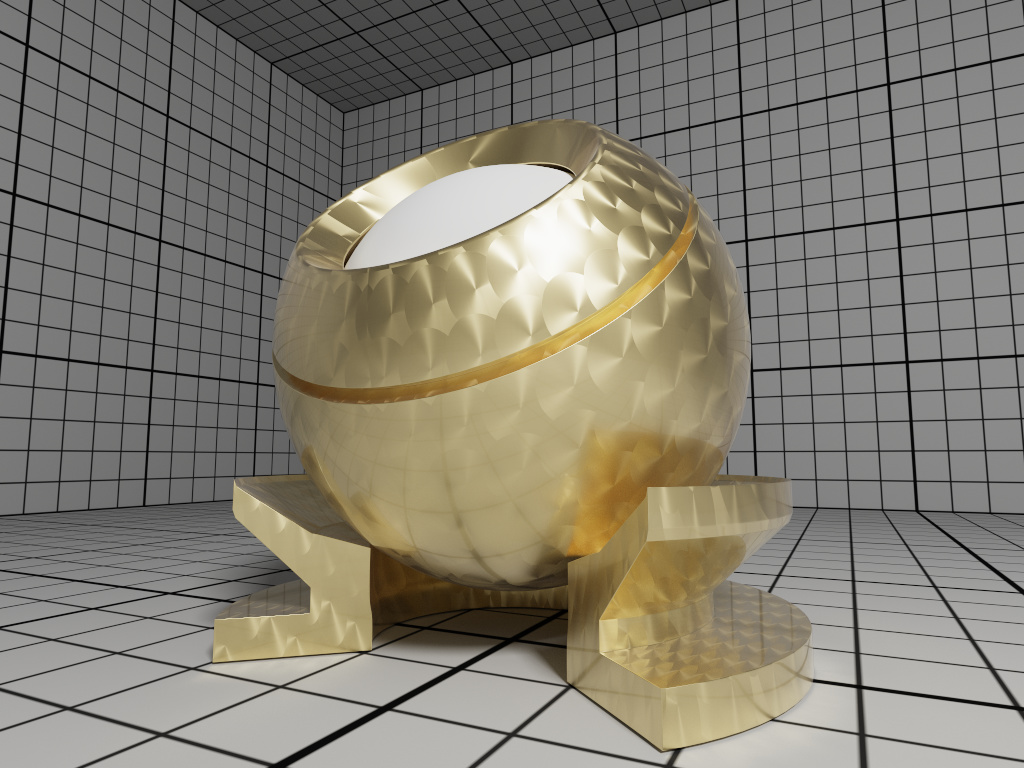

The path tracer offers a physical metal, supporting

changing roughness and realistic color shifts at edges. To create a

Metal material pass the type string “Metal” to ospNewMaterial2. Its

parameters are

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3f[] | ior | Aluminium | data array of spectral samples of complex refractive index, each entry in the form (wavelength, eta, k), ordered by wavelength (which is in nm) |

| vec3f | eta | RGB complex refractive index, real part | |

| vec3f | k | RGB complex refractive index, imaginary part | |

| float | roughness | 0.1 | roughness in [0–1], 0 is perfect mirror |

: Parameters of the Metal material.

The main appearance (mostly the color) of the Metal material is

controlled by the physical parameters eta and k, the

wavelength-dependent, complex index of refraction. These coefficients

are quite counterintuitive but can be found in published

measurements. For accuracy the index of

refraction can be given as an array of spectral samples in ior, each

sample a triplet of wavelength (in nm), eta, and k, ordered

monotonically increasing by wavelength; OSPRay will then calculate the

Fresnel in the spectral domain. Alternatively, eta and k can also be

specified as approximated RGB coefficients; some examples are given in

below table.

| Metal | eta | k |

|---|---|---|

| Ag, Silver | (0.051, 0.043, 0.041) | (5.3, 3.6, 2.3) |

| Al, Aluminium | (1.5, 0.98, 0.6) | (7.6, 6.6, 5.4) |

| Au, Gold | (0.07, 0.37, 1.5) | (3.7, 2.3, 1.7) |

| Cr, Chromium | (3.2, 3.1, 2.3) | (3.3, 3.3, 3.1) |

| Cu, Copper | (0.1, 0.8, 1.1) | (3.5, 2.5, 2.4) |

: Index of refraction of selected metals as approximated RGB coefficients, based on data from https://refractiveindex.info/.

The roughness parameter controls the variation of microfacets and thus

how polished the metal will look. The roughness can be modified by a

texture map_roughness ([texture transformations] are

supported as well) to create interesting edging effects.

The path tracer offers an alloy material, which behaves

similar to Metal, but allows for more intuitive and flexible

control of the color. To create an Alloy material pass the type string

“Alloy” to ospNewMaterial2. Its parameters are

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3f | color | white 0.9 | reflectivity at normal incidence (0 degree) |

| vec3f | edgeColor | white | reflectivity at grazing angle (90 degree) |

| float | roughness | 0.1 | roughness, in [0–1], 0 is perfect mirror |

: Parameters of the Alloy material.

The main appearance of the Alloy material is controlled by the parameter

color, while edgeColor influences the tint of reflections when seen

at grazing angles (for real metals this is always 100% white). If

present, the color component of geometries is also used

for reflectivity at normal incidence color. As in Metal the

roughness parameter controls the variation of microfacets and thus how

polished the alloy will look. All parameters can be textured by passing

a texture handle, prefixed with “map_”; [texture

transformations] are supported as well.

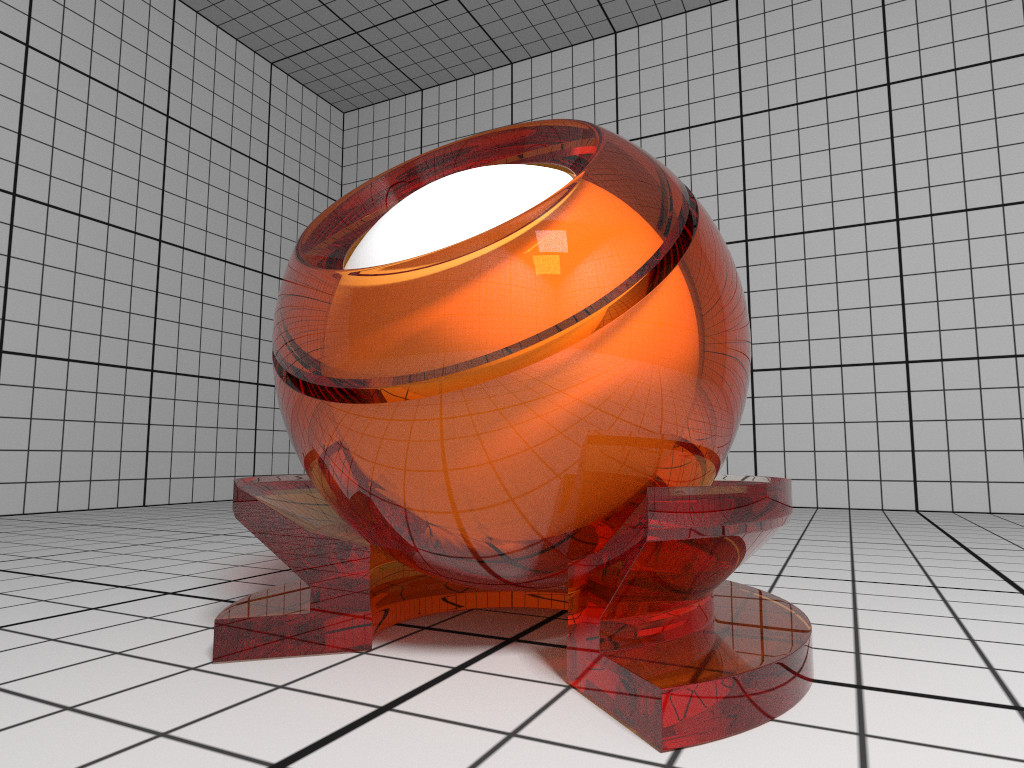

The path tracer offers a realistic a glass material,

supporting refraction and volumetric attenuation (i.e. the transparency

color varies with the geometric thickness). To create a Glass material

pass the type string “Glass” to ospNewMaterial2. Its parameters are

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| float | eta | 1.5 | index of refraction |

| vec3f | attenuationColor | white | resulting color due to attenuation |

| float | attenuationDistance | 1 | distance affecting attenuation |

: Parameters of the Glass material.

For convenience, the rather counterintuitive physical attenuation

coefficients will be calculated from the user inputs in such a way, that

the attenuationColor will be the result when white light traveled

trough a glass of thickness attenuationDistance.

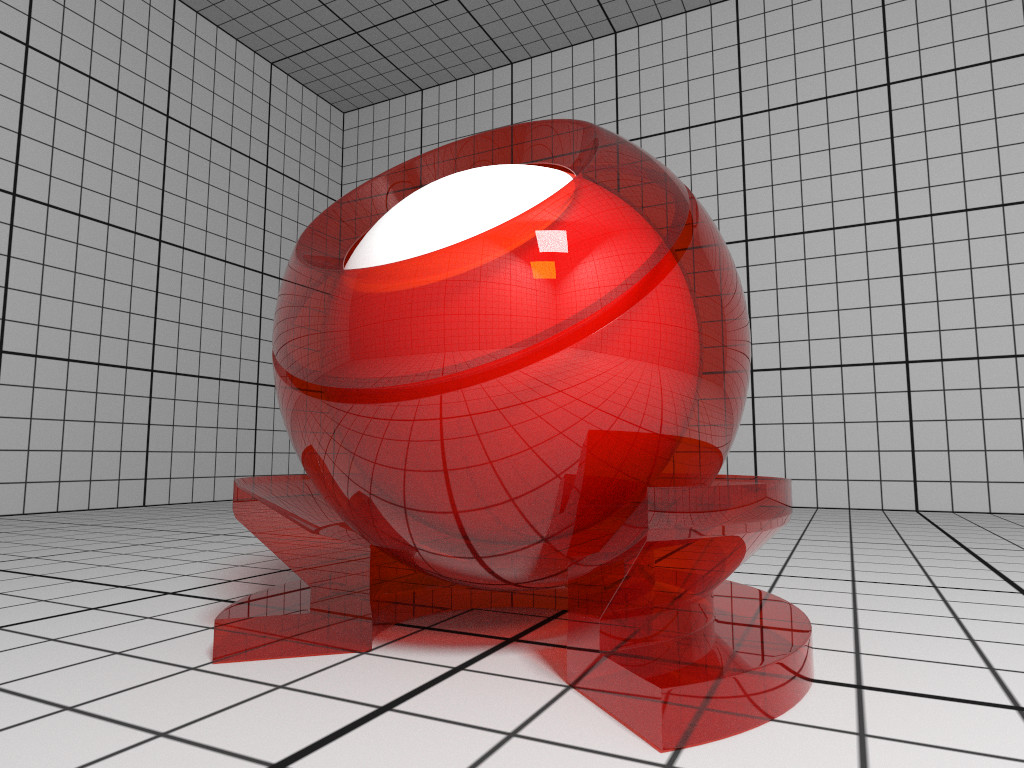

The path tracer offers a thin glass material useful for

objects with just a single surface, most prominently windows. It models

a very thin, transparent slab, i.e. it behaves as if a second, virtual

surface is parallel to the real geometric surface. The implementation

accounts for multiple internal reflections between the interfaces

(including attenuation), but neglects parallax effects due to its

(virtual) thickness. To create a such a thin glass material pass the

type string “ThinGlass” to ospNewMaterial2. Its parameters are

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| float | eta | 1.5 | index of refraction |

| vec3f | attenuationColor | white | resulting color due to attenuation |

| float | attenuationDistance | 1 | distance affecting attenuation |

| float | thickness | 1 | virtual thickness |

: Parameters of the ThinGlass material.

For convenience the attenuation is controlled the same way as with the

Glass material. Additionally, the color due to attenuation can

be modulated with a texture map_attenuationColor

([texture transformations] are supported as well). If present, the

color component of geometries is also used for the

attenuation color. The thickness parameter sets the (virtual)

thickness and allows for easy exchange of parameters with the (real)

Glass material; internally just the ratio between

attenuationDistance and thickness is used to calculate the resulting

attenuation and thus the material appearance.

The path tracer offers a metallic paint material,

consisting of a base coat with optional flakes and a clear coat. To

create a MetallicPaint material pass the type string “MetallicPaint”

to ospNewMaterial2. Its parameters are listed in the table below.

| Type | Name | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| vec3f | baseColor | white 0.8 | color of base coat |

| float | flakeAmount | 0.3 | amount of flakes, in [0–1] |

| vec3f | flakeColor | Aluminium | color of metallic flakes |

| float | flakeSpread | 0.5 | spread of flakes, in [0–1] |

| float | eta | 1.5 | index of refraction of clear coat |

: Parameters of the MetallicPaint material.

The color of the base coat baseColor can be textured by a

texture map_baseColor, which also supports [texture

transformations]. If present, the color component of

geometries is also used for the color of the base coat.

parameter flakeAmount controls the proportion of flakes in the base

coat, so when setting it to 1 the baseColor will not be visible. The

shininess of the metallic component is governed by flakeSpread, which

controls the variation of the orientation of the flakes, similar to the

roughness parameter of Metal. Note that the effect of the

metallic flakes is currently only computed on average, thus individual

flakes are not visible.

The path tracer supports the Luminous material which

emits light uniformly in all directions and which can thus be used to

turn any geometric object into a light source. It is created by passing

the type string “Luminous” to ospNewMaterial2. The amount of

constant radiance that is emitted is determined by combining the general

parameters of lights: color and intensity.

OSPRay currently implements two texture types (texture2d and volume)

and is open for extension to other types by applications. More types may

be added in future releases.

To create a new texture use

OSPTexture ospNewTexture(const char *type);

The call returns NULL if the texture could not be created with the

given parameters, or else an OSPTexture handle to the created texture.

The texture2D texture type implements an image-based texture, where

its parameters are as follows

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec2f | size | size of the textures |

| int | type | OSPTextureFormat for the texture |

| int | flags | special attribute flags for this |

| texture, currently only responds | ||

to OSP_TEXTURE_FILTER_NEAREST or |

||

| no flags | ||

| OSPData | data | the actual texel data |

: Parameters of texture2D texture type

The supported texture formats for texture2d are:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| OSP_TEXTURE_RGBA8 | 8 bit [0–255] linear components red, green, blue, alpha |

| OSP_TEXTURE_SRGBA | 8 bit sRGB gamma encoded color components, and linear alpha |

| OSP_TEXTURE_RGBA32F | 32 bit float components red, green, blue, alpha |

| OSP_TEXTURE_RGB8 | 8 bit [0–255] linear components red, green, blue |

| OSP_TEXTURE_SRGB | 8 bit sRGB gamma encoded components red, green, blue |

| OSP_TEXTURE_RGB32F | 32 bit float components red, green, blue |

| OSP_TEXTURE_R8 | 8 bit [0–255] linear single component |

| OSP_TEXTURE_R32F | 32 bit float single component |

: Supported texture formats by texture2D, i.e. valid constants of type

OSPTextureFormat.

The texel data addressed by source starts with the texels in the lower

left corner of the texture image, like in OpenGL. Per default a texture

fetch is filtered by performing bi-linear interpolation of the nearest

2×2 texels; if instead fetching only the nearest texel is desired (i.e.

no filtering) then pass the OSP_TEXTURE_FILTER_NEAREST flag.

The volume texture type implements texture lookups based on 3D world

coordinates of the surface hit point on the associated geometry. If the

given hit point is within the attached volume, the volume is sampled and

classified with the transfer function attached to the volume. This

implements the ability to visualize volume values (as colored by its

transfer function) on arbitrary surfaces inside the volume (as opposed

to an isosurface showing a particular value in the volume). Its

parameters are as follows

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| OSPVolume | volume | volume used to generate color lookups |

: Parameters of volume texture type

All materials with textures also offer to manipulate the placement of

these textures with the help of texture transformations. If so, this

convention shall be used. The following parameters (prefixed with

“texture_name.”) are combined into one transformation matrix:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec4f | transform | interpreted as 2×2 matrix (linear part), column-major |

| float | rotation | angle in degree, counterclockwise, around center |

| vec2f | scale | enlarge texture, relative to center (0.5, 0.5) |

| vec2f | translation | move texture in positive direction (right/up) |

: Parameters to define texture coordinate transformations.

The transformations are applied in the given order. Rotation, scale and translation are interpreted “texture centric”, i.e. their effect seen by an user are relative to the texture (although the transformations are applied to the texture coordinates).

To create a new camera of given type type use

OSPCamera ospNewCamera(const char *type);

The call returns NULL if that type of camera is not known, or else an

OSPCamera handle to the created camera. All cameras accept these

parameters:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vec3f(a) | pos | position of the camera in world-space |

| vec3f(a) | dir | main viewing direction of the camera |

| vec3f(a) | up | up direction of the camera |

| float | nearClip | near clipping distance |

| vec2f | imageStart | start of image region (lower left corner) |

| vec2f | imageEnd | end of image region (upper right corner) |

: Parameters accepted by all cameras.

The camera is placed and oriented in the world with pos, dir and

up. OSPRay uses a right-handed coordinate system. The region of the

camera sensor that is rendered to the image can be specified in

normalized screen-space coordinates with imageStart (lower left

corner) and imageEnd (upper right corner). This can be used, for

example, to crop the image, to achieve asymmetrical view frusta, or to

horizontally flip the image to view scenes which are specified in a

left-handed coordinate system. Note that values outside the default

range of [0–1] are valid, which is useful to easily realize overscan

or film gate, or to emulate a shifted sensor.

The perspective camera implements a simple thinlens camera for

perspective rendering, supporting optionally depth of field and stereo

rendering, but no motion blur. It is created by passing the type string

“perspective” to ospNewCamera. In addition to the general

parameters understood by all cameras the perspective camera

supports the special parameters listed in the table below.

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| float | fovy | the field of view (angle in degree) of the frame’s height |

| float | aspect | ratio of width by height of the frame |

| float | apertureRadius | size of the aperture, controls the depth of field |

| float | focusDistance | distance at where the image is sharpest when depth of field is enabled |

| bool | architectural | vertical edges are projected to be parallel |

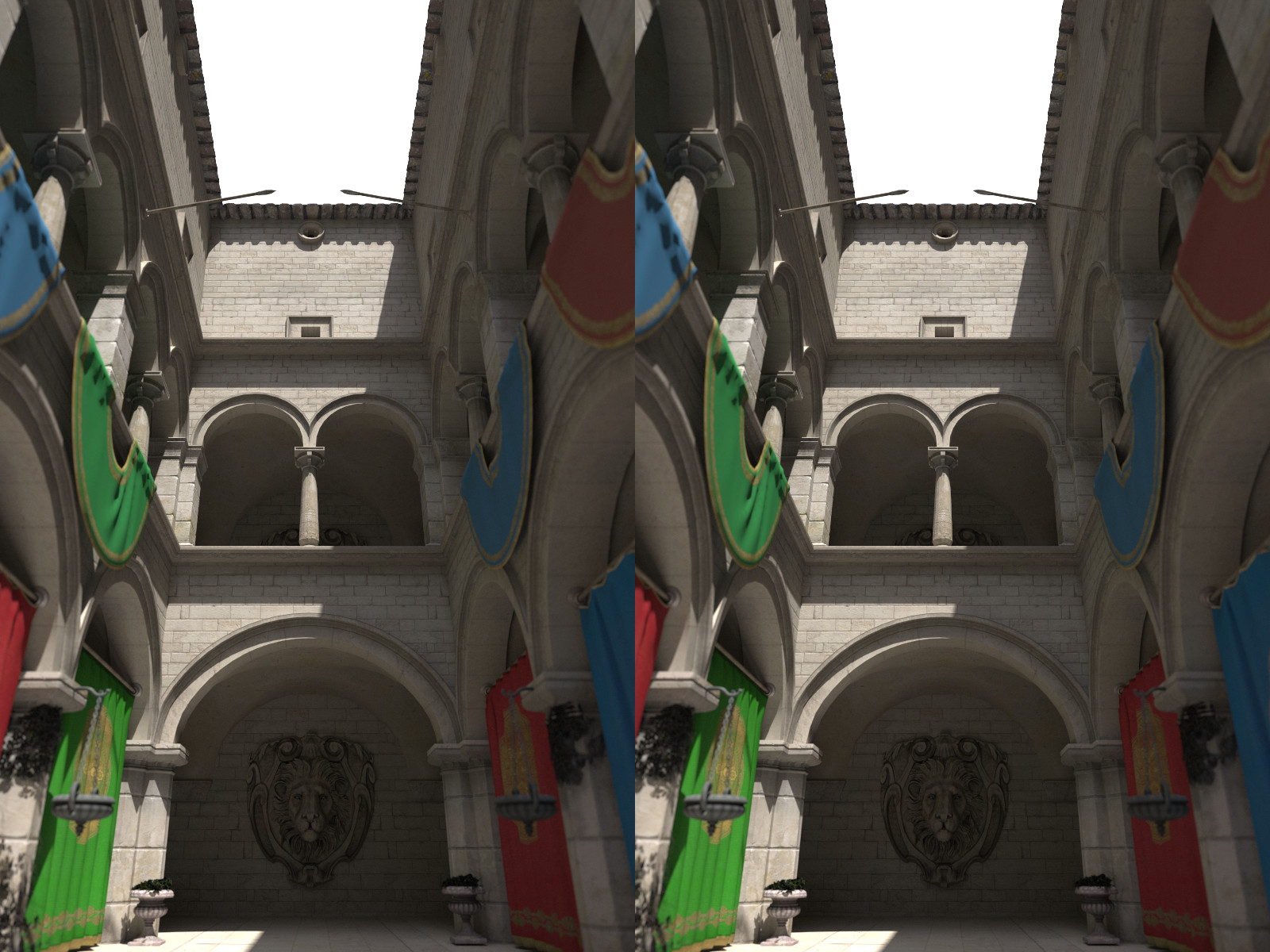

| int | stereoMode | 0: no stereo (default), 1: left eye, 2: right eye, 3: side-by-side |

| float | interpupillaryDistance | distance between left and right eye when stereo is enabled |

: Parameters accepted by the perspective camera.

Note that when setting the aspect ratio a non-default image region

(using imageStart & imageEnd) needs to be regarded.

In architectural photography it is often desired for aesthetic reasons

to display the vertical edges of buildings or walls vertically in the

image as well, regardless of how the camera is tilted. Enabling the

architectural mode achieves this by internally leveling the camera

parallel to the ground (based on the up direction) and then shifting

the lens such that the objects in direction dir are centered in the

image. If finer control of the lens shift is needed use imageStart &

imageEnd. Because the camera is now effectively leveled its image

plane and thus the plane of focus is oriented parallel to the front of

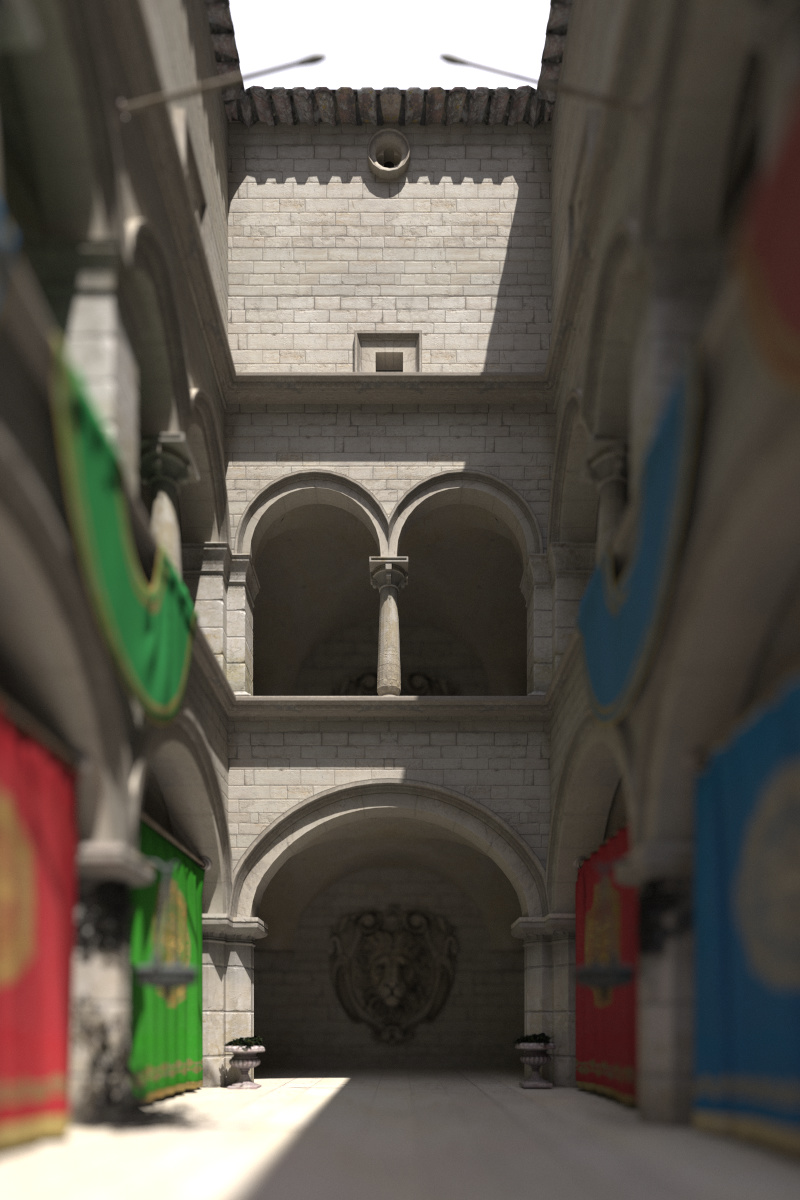

buildings, the whole façade appears sharp, as can be seen in the example

images below.

architectural flag corrects the perspective projection distortion, resulting in parallel vertical edges.

Example 3D stereo image using stereoMode side-by-side.

#### Orthographic Camera

The orthographic camera implements a simple camera with orthographic

projection, without support for depth of field or motion blur. It is

created by passing the type string “orthographic” to ospNewCamera.

In addition to the general parameters understood by all

cameras the orthographic camera supports the following special

parameters:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| float | height | size of the camera’s image plane in y, in world coordinates |

| float | aspect | ratio of width by height of the frame |

: Parameters accepted by the orthographic camera.

For convenience the size of the camera sensor, and thus the extent of

the scene that is captured in the image, can be controlled with the

height parameter. The same effect can be achieved with imageStart

and imageEnd, and both methods can be combined. In any case, the

aspect ratio needs to be set accordingly to get an undistorted image.

The panoramic camera implements a simple camera without support for

motion blur. It captures the complete surrounding with a latitude /

longitude mapping and thus the rendered images should best have a ratio

of 2:1. A panoramic camera is created by passing the type string

“panoramic” to ospNewCamera. It is placed and oriented in the scene

by using the general parameters understood by all cameras.

To get the world-space position of the geometry (if any) seen at [0–1]

normalized screen-space pixel coordinates screenPos use

void ospPick(OSPPickResult*, OSPRenderer, const vec2f &screenPos);

The result is returned in the provided OSPPickResult struct:

typedef struct {

vec3f position; // the position of the hit point (in world-space)

bool hit; // whether or not a hit actually occurred

} OSPPickResult;

Note that ospPick considers exactly the same camera of the given

renderer that is used to render an image, thus matching results can be

expected. If the camera supports depth of field then the center of the

lens and thus the center of the circle of confusion is used for picking.

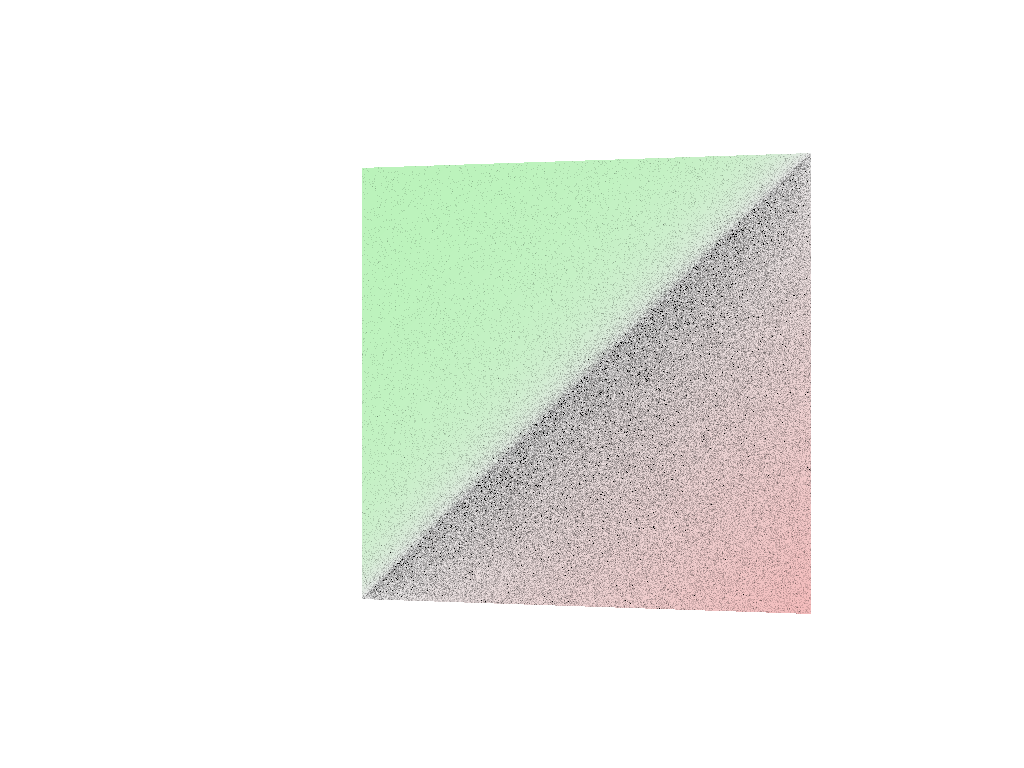

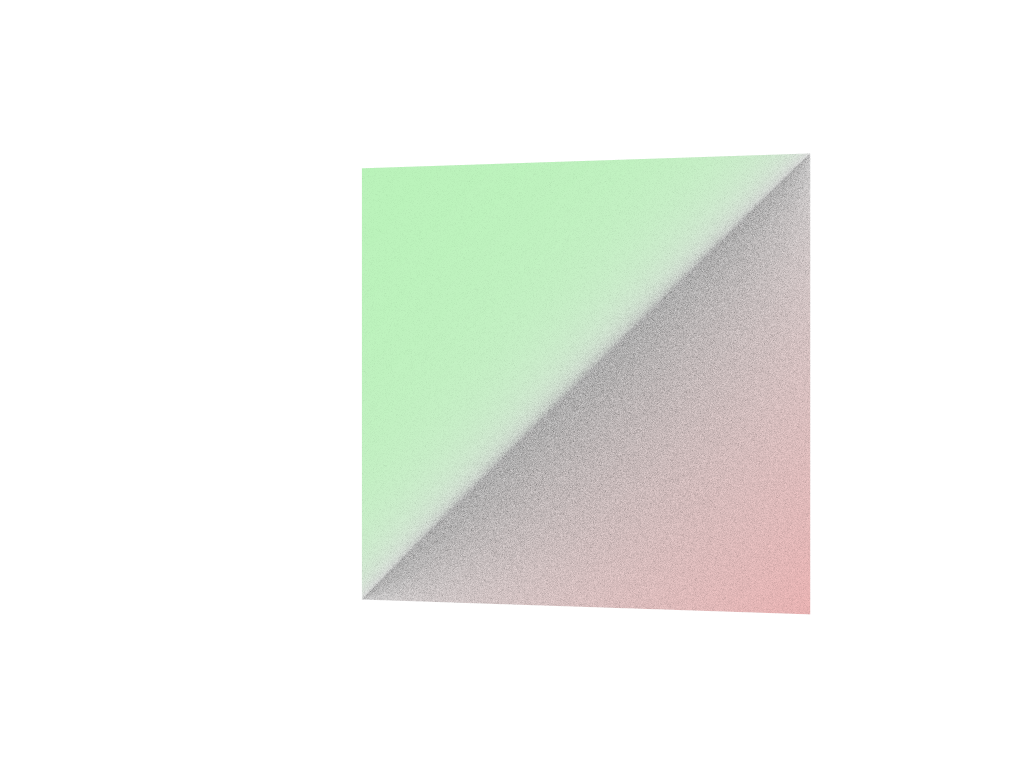

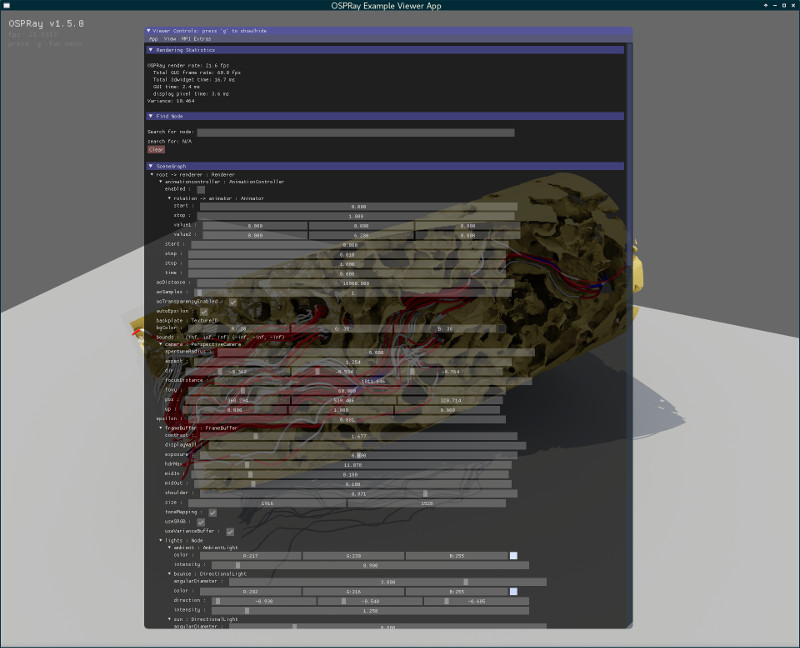

The framebuffer holds the rendered 2D image (and optionally auxiliary