-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 113

Design

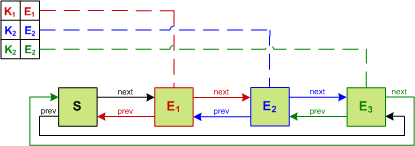

LinkedHashMap provides a convenient data structure that maintains the ordering of entries within the hash-table. This is accomplished by cross-cutting the hash-table with a doubly-linked list, so that entries can be removed or reordered in O(1) time. When operating in access-order an entry is retrieved, unlinked, and relinked at the tail of the list. The result is that the head element is the least recently used and the tail element is the most recently used. When bounded, this class becomes a convenient LRU cache.

The problem with this approach is that every access operation requires updating the list. To function in a concurrent setting the entire data structure must be synchronized.

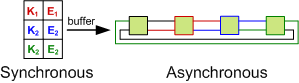

An alternative approach is to realize that the data structure can be split into two parts: a synchronous view and an asynchronous view. The hash-table must be synchronous from the perspective of the caller so that a read after a write returns the expected value. The list, however, does not have any visible external properties.

This observation allows the operations on the list to be applied lazily by buffering them. This allows threads to avoid needing to acquire the lock and the buffer can be drained in a non-blocking fashion. Instead of incurring lock contention, the penalty of draining the buffer is amortized across threads. This drain must be performed when either the buffer exceeds a threshold size or a write is performed.

A single buffer provides FIFO semantics so that a drain applies each operation in the correct order. However, a single buffer can become a point of contention as the concurrency level increases.

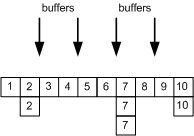

The usage of multiple buffers improves concurrency at the cost of no longer maintaining order. This can be resolved by tagging each operation with an id and sorting the operations prior to applying them. To avoid the counter from causing contention, it can be racy to allow duplicate ids. The combination of counting sort and closed addressing reduces the runtime cost to an O(n) sort.

To allow better concurrency characteristics, the operations may be processed out-of-order. However, doing so could result in a corrupted state such as by processing the removal prior to the addition of an entry. A simple state machine allows for resolving these race conditions so that a strict ordering is not required.

| State | Description |

|---|---|

| Alive | The entry is in both the hash-table and the page replacement policy |

| Retired | The entry is not in the hash-table and is pending removal from the page replacement policy |

| Dead | The entry is not in the hash-table and is not in the page replacement policy |

The least recently used policy provides a good reference point. It does not suffer degradation scenarios as the cache size increases, it provides a reasonably good hit rate, and can be implemented with O(1) time complexity.

However, an LRU policy only utilizes the recency of an entry and does not take advantage of its frequency. The low inter-reference recency set replacement policy does, while also maintaining the same beneficial characteristics. This allows improving the hit rate at a very low cost.

An additional advantage of LIRS is that the strictness of draining the buffers can be loosened. By leveraging frequency to make up for a weakened recency constraint, the pending operations do not need to be drain in a sorted order. This allows for reducing the amortized penalty at a minimal impact to the hit rate.

A cache may decide to allow the the capacity consumed by an entry to differ between them. For example, a cache that limits by memory usage may have entries that take up more space than others. This is called the weight of the entry.

If all entries are assigned a weight of 1 then the LIRS policy can be taken advantage of. Unfortunately, this policy does not work well with weighted entries due to constantly resizing its internal data structures.

If weights are specified then the cache can degrade to an LRU policy to maintain a satisfactory hit rate. Alternatively, the greedy dual size frequency policy can be used which takes into account the weight when determining which entry to evict.

ConcurrentLinkedHashMap has been used to prove out these ideas in isolation, but our long-term goal is to bring them into Google's MapMaker. In our initial efforts towards that we began seeing other usages for lock amortization.

Expiration is a perfect fit. In a time-to-idle policy the entry's time window is reset on every access. This can be viewed as a an LRU policy where the constraint is a time bounding instead of the maximum size. If an access-ordered list is maintained then both constraints can be applied. Similarly a time-to-live policy can be cleaned up during the drain process.

The cleanup of entries that were invalidated due to soft and weak garbage collection can be amortized on user threads during the draining process. This allows making the background thread optional, which may be useful for eager cleanup during inactivity but not always allowed by the SecurityManager.

BP-Wrapper: A System Framework Making Any Replacement Algorithms (Almost) Lock Contention Free

Flat Combining and the Synchronization-Parallelism Tradeoff

Scalable Flat-Combining Based Synchronous Queues

The Performance Impact of Kernel Prefetching on Buffer Cache Replacement Algorithms

Improving WWW Proxies Performance with Greedy-Dual-Size-Frequency Caching Policy