| title | description | tags | author | excerpt | publishedAt | originalURL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

XState: version 4.7 and the future |

XState version 4.7 has just been released. This is a minor version bump, but a major reworking of the internal algorithms, a lot of new capabilites, bug fixes and a better TypeScript experience. |

|

David Khourshid |

2019-12-09 |

XState version 4.7 has just been released. This is a minor version bump, but a major reworking of the internal algorithms, a lot of new capabilities, bug fixes, and a better TypeScript experience. It also paves the road for even more utilities, like @xstate/test and @xstate/react, as well as compatibility with other 3rd-party tools across the ecosystem, and even across languages.

XState is a JavaScript (and TypeScript) library for creating state machines and statecharts, and interpreting them. State machines enforce a specific set of ”rules“ on logic structure such that:

- There are a finite number of states (such as

"loading"or"success"), which is different than context (related data with potentially infinite possibilities, such asemailorage) - There are a finite number of events (such as

{ type: 'FETCH', query: "..." }that can trigger a transition between states. - Each state has transitions, which say, ”Given some event, go to this next state and/or do these actions”.

You don’t need a state machine library to do this, as you can use switch statements instead:

switch (state.status) {

case 'idle': // finite state

switch (event.type) {

case 'FETCH':

return {

...state,

status: 'loading',

query: event.query

};

// ...

// ...

// ...

}But let’s be honest, writing it like this is arguably a bit cleaner:

const machine = Machine({

initial: "idle",

states: {

idle: {

on: {

FETCH: {

target: "loading",

actions: assign({ query: (_, event) => event.query }),

},

},

},

// ...

},

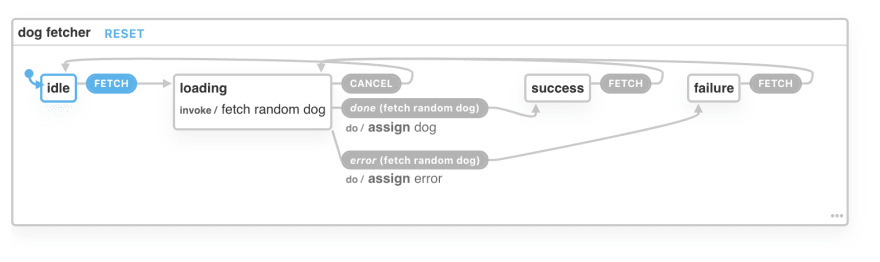

});And it also makes it possible to directly copy-paste this machine code into a visualizer, like XState Viz, and visualize it, like was done at the end of the No, disabling a button is not app logic article:

Then there are statecharts, which are an extension of finite state machines created by David Harel in 1989 (read the paper 📑). Statecharts offer many improvements and mitigate many issues of using flat finite state machines, such as:

- Nested states (hierarchy)

- Parallel states (orthogonality)

- History states

- Entry, exit, and transition actions

- Transient states

- Activities (ongoing actions)

- Communication with many machines (invoked services)

- Delayed transitions

- And much more

These are things that you definitely do not want to implement yourself, which is why libraries like XState exist. And this brings us to…

This minor release has been worked on for months, with a huge amount of help from Mateusz Burzyński (also known as AndaristRake) 👏. The reason it took so long was because we are internally reworking the algorithms to be simpler, fit the SCXML spec, and be compatible with a growing number of tools in the ecosystem. This refactoring also makes adding new capabilities much easier, and will hopefully encourage more contributors to help with this project. As a nice side-effect, it also eliminates a few edge-case bugs that had workarounds, but might have caused a suboptimal developer experience in previous versions.

How difficult can it be to create a statechart library? A lot more difficult than it seems, especially if you want to conform to the long, but well-established SCXML spec. There’s even libraries for integrating SCXML code directly with JavaScript, such as Jacob Beard’s excellent SCION tools, which I highly recommend you check out. It was a huge inspiration for XState, and XState is tested against much of the same code.

SCXML specifies an algorithm for SCXML interpretation, which is written in pseudocode, but directly transferable to many popular languages. This algorithm was followed more closely in the refactor, which simplified a lot of the code base and removed the need for ad-hoc data structures such as StateTree, which was used to keep track of which state nodes were "active" for a given transition (now it’s just a set).

As a result, the core code base is a little smaller, the algorithms are a little bit faster (determining the next state is basically an O(1) lookup, O(n) worst-case), and the code base is a lot nicer to work with and contribute to. We will continue to improve the algorithms used as we move towards 5.0.

Typestates are really useful for developers. They’re popular in Rust, and this article on The Typestate Pattern in Rust describes them elegantly:

Typestates are a technique for moving properties of state (the dynamic information a program is processing) into the type level (the static world that the compiler can check ahead-of-time).

Without learning Rust or diving into the Wikipedia article, let’s present a classic example: loading data. You might represent the state’s context in this way:

interface User {

name: string;

}

interface UserContext {

user?: User;

error?: string;

}This type-safe declaration allows you to defensively program effectively, but it can be a bit annoying when you are 100% sure that user is defined:

if (state.matches("success")) {

if (!state.context.user) {

// this should be impossible!

// the user definitely exists!

throw new Error("Something weird happened");

}

return state.context.user.name;

}In 4.7, XState allows you to represent your states with Typestates so that you can tell the compiler that you know how the context should be in any given state:

This is very useful and improves the developer experience, but should be used as a strong guide, and not as a guarantee. It works by using discriminated unions in TypeScript to define your states, but the way it is implemented requires TypeScript version 3.7 and higher. There’s still some quirks to work out, as we’re basically trying to trick TypeScript into knowing some extra information about our state machines that is otherwise difficult/impossible to infer in a statically typed language. (Maybe one day JavaScript will have a dependently-typed flavor.)

XState makes invoking external ”services” a first-class citizen. If this is a foreign concept, for now, just understand that it answers the question “how can many state machines communicate with each other?”, and the answer is by using events as the main communication mechanism. In 4.7, the developer experience for this is improved:

- Invoked services can now be referenced on the

state.childrenobject by their ID. So if a state invokes some service withid: 'fetchUser', then that invocation will be present onstate.children.fetchUser. - The new

forwardTo()action creator allows you to forward events to invoked services, which cuts down a lot of boilerplate:

on: {

SOME_EVENT: {

actions: forwardTo("someService");

}

}- SCXML has this notion of a

sessionid, which is a unique identifier for each invoked service. XState 4.7 becomes more SCXML-compatible by keeping a reference of this instate._sessionid, which corresponds to the SCXML_sessionidvariable. - XState can use that

_sessionidto determine which service sent an event, so it can respond with an event back, using the newrespond()action creator:

const authServerMachine = Machine({

initial: "waitingForCode",

states: {

waitingForCode: {

on: {

CODE: {

actions: respond("TOKEN", { delay: 10 }),

},

},

},

},

});

const authClientMachine = Machine({

initial: "idle",

states: {

idle: {

on: { AUTH: "authorizing" },

},

authorizing: {

invoke: {

id: "auth-server",

src: authServerMachine,

},

entry: send("CODE", { to: "auth-server" }),

on: {

TOKEN: "authorized",

},

},

authorized: {

type: "final",

},

},

});You can make your own custom action creators too, and implement patterns that you might be familiar with already if you’ve worked with microservices.

If you’ve ever wanted to transition from a state if any (unspecified) event is received? Well, you’re in luck, because XState now supports wildcard descriptors, which are a type of event descriptor (SCXML) that describes a transition for any event in a given state:

const quietMachine = Machine({

id: "quiet",

initial: "idle",

states: {

idle: {

on: {

WHISPER: undefined,

// On any event besides a WHISPER, transition to the 'disturbed' state

"*": "disturbed",

},

},

disturbed: {},

},

});

quietMachine.transition(quietMachine.initialState, "WHISPER");

// => State { value: 'idle' }

quietMachine.transition(quietMachine.initialState, "SOME_EVENT");

// => State { value: 'disturbed' }See https://github.com/davidkpiano/xstate/releases/tag/v4.7.0 for an overview of the latest updates in this minor version.

All this leads to the big question: what are the future plans/goals for XState? The first important thing to realize is that XState is not just another state management library, and state management was never its only goal. XState strives to bring two things to the JavaScript ecosystem:

- State machines/statecharts, for modeling the logic of any individual component

- Actor model, for modeling how components communicate with each other and behave in a system

All of these are very old, very useful, and battle-tested concepts. The benefits they provide cannot be understated, and highlight the future plans for XState and related tooling:

- Better visualization tools, including an updated visualizer, dev tools for Firefox and Chrome (work in progress!), dev tools for VS Code, and integration with other graphical viz tools such as PlantUML and GraphViz

- Full SCXML compatibility, which will allow statecharts authored in XState to be reusable in other languages that have SCXML tooling, as it is a truly language-agnostic spec

- A catalog of examples, to demonstrate common patterns and best practices for many use-cases

- Analytics, testing, and simulation tools

As well as some initial ideas for XState version 5.0:

- Better type safety and a more seamless TypeScript experience

- Static analysis tools for compile-time hints/warnings and run-time optimizations

- A more ”functional”, and completely optional, syntax for defining states and transitions more naturally (developer experience)

- Higher-level state types such as

"task"and"choice"to make it easier to define workflows and remove some boilerplate

We’re also listening to ideas that you present to us in the XState Wish List thread, so post what you would like to see!

If you’re curious about XState or statecharts in general, there are many fantastic resources, including:

- The World of Statecharts by Erik Mogensen

- Statecharts community on Spectrum

- XState docs

- Other tutorials made by many excellent developers in the community