diff --git a/learning-pathways/data-driven-biology.md b/learning-pathways/data-driven-biology.md

index e3f6005ae6f9bc..aca23c00135bfd 100644

--- a/learning-pathways/data-driven-biology.md

+++ b/learning-pathways/data-driven-biology.md

@@ -26,6 +26,12 @@ pathway:

topic: data-science

- name: cli-advanced

topic: data-science

+ - name: python-basics

+ topic: data-science

+ - name: gnmx-lecture2

+ topic: data-science

+ - name: gnmx-lecture3

+ topic: data-science

---

diff --git a/topics/data-science/tutorials/gnmx-lecture3/images/qualities.svg b/topics/data-science/tutorials/gnmx-lecture3/images/qualities.svg

new file mode 100644

index 00000000000000..567eb86d634bba

--- /dev/null

+++ b/topics/data-science/tutorials/gnmx-lecture3/images/qualities.svg

@@ -0,0 +1,138 @@

+

\ No newline at end of file

diff --git a/topics/data-science/tutorials/gnmx-lecture3/tutorial.md b/topics/data-science/tutorials/gnmx-lecture3/tutorial.md

new file mode 100644

index 00000000000000..021be2a2b35a1d

--- /dev/null

+++ b/topics/data-science/tutorials/gnmx-lecture3/tutorial.md

@@ -0,0 +1,812 @@

+---

+layout: tutorial_hands_on

+

+title: "Introduction to sequencing with Python (part two)"

+questions:

+ - What is FASTQ format

+ - How do I parse FASTQ format with Python

+ - How do I decide whether my data is good or not?

+objectives:

+ - Understand manipulation of FASTQ data in Python

+ - Understand quality metrics

+time_estimation: "1h"

+key_points:

+ - Python can be used to parse FASTQ easily

+ - One can readily visualize quality values

+contributions:

+ authorship:

+ - nekrut

+

+subtopic: gnmx

+draft: true

+

+notebook:

+ language: python

+ pyolite: true

+---

+

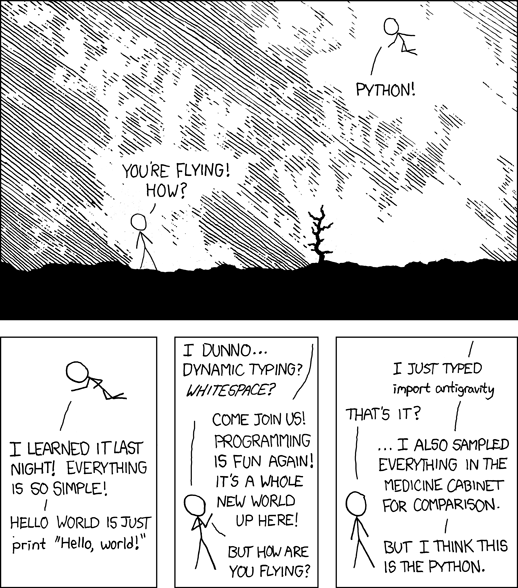

+[](https://xkcd.com/353/)

+

+Preclass prep: Chapters [8](https://greenteapress.com/thinkpython2/html/thinkpython2009.html) and [10](https://greenteapress.com/thinkpython2/html/thinkpython2011.html) from "Think Python"

+

+> This material uses examples from notebooks developed by [Ben Langmead](https://langmead-lab.org/teaching-materials/)

+{: .quote cite="https://langmead-lab.org/teaching-materials" }

+

+# Prep

+

+1. Start [JupyterLab](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/jupyterlab/jupyterlab-demo/try.jupyter.org?urlpath=lab)

+2. Within JupyterLab start a new Python3 notebook

+3. Open [this page](http://cs1110.cs.cornell.edu/tutor/#mode=edit) in a new browser tab

+

+# Strings in Python

+

+In Python, strings are sequences of characters enclosed in quotation marks (either single or double quotes). They can be assigned to a variable and manipulated using various string methods. For example:

+

+string1 = "Hello World!"

+string2 = 'Hello World!'

+

+print(string1) # Output: Hello World!

+print(string2) # Output: Hello World!

+

+You can also use the + operator to concatenate strings, and the * operator to repeat a string a certain number of times:

+

+

+```python

+string3 = "Hello " + "World!"

+print(string3) # Output: Hello World!

+

+string4 = "Hello " * 3

+print(string4) # Output: Hello Hello Hello

+```

+

+ Hello World!

+ Hello Hello Hello

+

+

+There are also many built-in string methods such as `upper()`, `lower()`, `replace()`, `split()`, `find()`, `len()`, etc. These can be used to manipulate and extract information from strings:

+

+

+```python

+string5 = "Hello World!"

+print(string5.upper()) # Output: HELLO WORLD!

+print(string5.lower()) # Output: hello world!

+print(string5.replace("H", "J")) # Output: Jello World!

+print(string5.split(" ")) # Output: ['Hello', 'World!']

+```

+

+ HELLO WORLD!

+ hello world!

+ Jello World!

+ ['Hello', 'World!']

+

+

+You can also use indexing, slicing and string formatting to access or manipulate substrings or insert dynamic data into a string.

+

+

+```python

+name = "John"

+age = 30

+

+print("My name is {} and I am {} years old.".format(name, age))

+```

+

+ My name is John and I am 30 years old.

+

+You can also use f-strings, or formatted string literals, to embed expressions inside string literals.

+

+```python

+name = "John"

+age = 30

+

+print(f"My name is {name} and I am {age} years old.")

+```

+

+ My name is John and I am 30 years old.

+

+## String indexing

+

+In Python, strings are sequences of characters, and each character has a corresponding index, starting from 0.

+This means that we can access individual characters in a string using their index. This is called "string indexing".

+

+Here is an example:

+

+```python

+string = "Hello World!"

+print(string[0]) # Output: H

+print(string[1]) # Output: e

+print(string[-1]) # Output: !

+```

+

+ H

+ e

+ !

+

+You can also use negative indexing to access characters from the end of the string, with -1 being the last character, -2 the second to last and so on.

+

+You can also use slicing to extract a substring from a string. The syntax is `string[start:end:step]`, where `start` is the starting index, `end` is the ending index (not included), and step is the number of characters to skip between each index.

+

+```python

+string = "Hello World!"

+print(string[0:5]) # Output: Hello

+print(string[6:11]) # Output: World

+print(string[::2]) # Output: HloWrd

+```

+

+ Hello

+ World

+ HloWrd

+

+You can also use the string formatting method to get the string at the specific index.

+

+```python

+string = "Hello World!"

+index = 3

+print(f"The character at index {index} is: {string[index]}")

+```

+

+ The character at index 3 is: l

+

+

+## String functions

+

+In Python, many built-in string methods can be used to manipulate and extract information from strings. Here are some of the most commonly used ones:

+

+- `upper()`: Converts the string to uppercase

+- `lower()`: Converts the string to lowercase

+- `replace(old, new)`: Replaces all occurrences of the old substring with the new substring

+- `split(separator)`: Splits the string into a list of substrings using the specified separator

+- `find(substring)`: Returns the index of the first occurrence of the substring, or -1 if the substring is not found

+- `index(substring)`: Returns the index of the first occurrence of the substring or raises a ValueError if the substring is not found

+- `count(substring)`: Returns the number of occurrences of the substring

+- `join(iterable)`: Concatenates the elements of an iterable (such as a list or tuple) with the string as the separator

+- `strip()`: Removes leading and trailing whitespaces from the string

+- `lstrip()`: Removes leading whitespaces from the string

+- `rstrip()`: Removes trailing whitespaces from the string

+- `startswith(substring)`: Returns True if the string starts with the specified substring, False otherwise

+- `endswith(substring)`: Returns True if the string ends with the specified substring, False otherwise

+- `isalpha()`: Returns True if the string contains only alphabetic characters, False otherwise

+- `isdigit()`: Returns True if the string contains only digits, False otherwise

+- `isalnum()`: Returns True if the string contains only alphanumeric characters, False otherwise

+- `format()`: Formats the string by replacing placeholders with specified values

+- `len()`: Returns the length of the string

+

+Here is an example of some of these methods:

+

+

+```python

+string = "Hello World!"

+

+print(string.upper()) # Output: HELLO WORLD!

+print(string.lower()) # Output: hello world!

+print(string.replace("H", "J")) # Output: Jello World!

+print(string.split(" ")) # Output: ['Hello', 'World!']

+print(string.find("World")) # Output: 6

+print(string.count("l")) # Output: 3

+print(string.strip()) # Output: "Hello World!"

+print(string.startswith("Hello")) # Output: True

+print(string.endswith("World!")) # Output: True

+print(string.isalpha()) # Output: False

+print(string.isalnum()) # Output: False

+print(string.format()) # Output: Hello World!

+print(len(string)) # Output: 12

+```

+

+ HELLO WORLD!

+ hello world!

+ Jello World!

+ ['Hello', 'World!']

+ 6

+ 3

+ Hello World!

+ True

+ True

+ False

+ False

+ Hello World!

+ 12

+

+

+## Playing with strings

+

+```python

+st = 'ACGT'

+```

+

+

+```python

+len(st) # getting the length of a string

+```

+

+ 4

+

+```python

+'' # empty string (epsilon)

+```

+ ''

+

+```python

+len('')

+```

+

+ 0

+

+```python

+import random

+random.choice('ACGT') # generating a random nucleotide

+```

+ 'G'

+

+```python

+# now I'll make a random nucleotide string by concatenating random nucleotides

+st = ''.join([random.choice('ACGT') for _ in range(40)])

+st

+```

+

+ 'GCTATATCAATGTTATCCGTTTTCTGATGTCGCGAGGACA'

+

+

+```python

+st[1:3] # substring, starting at position 1 and extending up to but not including position 3

+# note that the first position is numbered 0

+```

+

+ 'CT'

+

+

+```python

+st[0:3] # prefix of length 3

+```

+

+ 'GCT'

+

+```python

+st[:3] # another way of getting the prefix of length 3

+```

+

+ 'GCT'

+

+```python

+st[len(st)-3:len(st)] # suffix of length 3

+```

+

+ 'ACA'

+

+```python

+st[-3:] # another way of getting the suffix of length 3

+```

+

+ 'ACA'

+

+```python

+st1, st2 = 'CAT', 'ATAC'

+```

+

+

+```python

+st1

+```

+

+

+ 'CAT'

+

+

+```python

+st2

+```

+

+ 'ATAC'

+

+

+```python

+st1 + st2 # concatenation of 2 strings

+```

+

+ 'CATATAC'

+

+

+# FASTQ

+

+This notebook explores [FASTQ], the most common format for storing sequencing reads.

+

+FASTA and FASTQ are rather similar, but FASTQ is almost always used for storing *sequencing reads* (with associated quality values), whereas FASTA is used for storing all kinds of DNA,

+RNA or protein sequences (without associated quality values).

+

+## Basic format

+Here's a single sequencing read in FASTQ format:

+

+ @ERR294379.100739024 HS24_09441:8:2203:17450:94030#42/1

+ AGGGAGTCCACAGCACAGTCCAGACTCCCACCAGTTCTGACGAAATGATGAGAGCTCAGAAGTAACAGTTGCTTTCAGTCCCATAAAAACAGTCCTACAA

+ +

+ BDDEEF?FGFFFHGFFHHGHGGHCH@GHHHGFAHEGFEHGEFGHCCGGGFEGFGFFDFFHBGDGFHGEFGHFGHGFGFFFEHGGFGGDGHGFEEHFFHGE

+

+It's spread across four lines. The four lines are:

+

+1. "`@`" followed by a read name

+2. Nucleotide sequence

+3. "`+`", possibly followed by some info, but ignored by virtually all tools

+4. Quality sequence (explained below)

+

+Here is a very simple Python function for parsing files of FASTQ records:

+

+

+```python

+def parse_fastq(fh):

+ """ Parse reads from a FASTQ filehandle. For each read, we

+ return a name, nucleotide-string, quality-string triple. """

+ reads = []

+ while True:

+ first_line = fh.readline()

+ if len(first_line) == 0:

+ break # end of file

+ name = first_line[1:].rstrip()

+ seq = fh.readline().rstrip()

+ fh.readline() # ignore line starting with +

+ qual = fh.readline().rstrip()

+ reads.append((name, seq, qual))

+ return reads

+

+fastq_string = '''@ERR294379.100739024 HS24_09441:8:2203:17450:94030#42/1

+AGGGAGTCCACAGCACAGTCCAGACTCCCACCAGTTCTGACGAAATGATG

++

+BDDEEF?FGFFFHGFFHHGHGGHCH@GHHHGFAHEGFEHGEFGHCCGGGF

+@ERR294379.136275489 HS24_09441:8:2311:1917:99340#42/1

+CTTAAGTATTTTGAAAGTTAACATAAGTTATTCTCAGAGAGACTGCTTTT

++

+@@AHFF?EEDEAF?FEEGEFD?GGFEFGECGE?9H?EEABFAG9@CDGGF

+@ERR294379.97291341 HS24_09441:8:2201:10397:52549#42/1

+GGCTGCCATCAGTGAGCAAGTAAGAATTTGCAGAAATTTATTAGCACACT

++

+CDAFA note on while True

+>

+>In Python, the while loop is used to repeatedly execute a block of code as long as a certain condition is true. The while True statement is a special case where the loop will run indefinitely until a break statement is encountered inside the loop.

+>

+>Here is an example of a while True loop:

+>

+>

+>```python

+>while True:

+> user_input = input("Enter 'q' to quit: ")

+> if user_input == 'q':

+> break

+> print("You entered:", user_input)

+>

+>print("Exited the loop")

+>```

+>```

+>Enter 'q' to quit: q

+>Exited the loop

+>```

+>

+>

+>In this example, the loop will keep asking for user input until the user enters the 'q' character, which triggers the break statement, and the loop is exited.

+>

+>It is important to be careful when using while True loops, as they will run indefinitely if a break statement is not included. This can cause the program to crash or hang, if not handled properly.

+>

+>Also, It is recommended to use `while True` loop with a `break` statement, in case you want to execute the loop until some specific condition is met, otherwise, it's not a good practice to use `while True`.

+>

+>It's a good practice to include a way for the user to exit the loop, such as the break statement in the example above, or a counter variable to keep track of the number of iterations.

+{: .comment}

+

+## Read name

+

+Read names often contain information about:

+

+1. The scientific study for which the read was sequenced. E.g. the string `ERR294379` (an [SRA accession number](http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/about/sra_format)) in the read names correspond to [this study](http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=ERR294379).

+2. The sequencing instrument, and the exact *part* of the sequencing instrument, where the DNA was sequenced. See the [FASTQ format](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FASTQ_format#Illumina_sequence_identifiers) Wikipedia article for specifics on how the Illumina software encodes this information.

+3. Whether the read is part of a *paired-end read* and, if so, which end it is. Paired-end reads will be discussed further below. The `/1` you see at the end of the read names above indicates the read is the first end from a paired-end read.

+

+## Quality values

+

+Quality values are probabilities. Each nucleotide in each sequencing read has an associated quality value. A nucleotide quality value encodes the probability that the nucleotide was *incorrectly called* by the sequencing instrument and its software. If the nucleotide is `A`, the corresponding quality value encodes the probability that the nucleotide at that position is actually *not* an `A`.

+

+Quality values are encoded in two senses: first, the relevant probabilities are re-scaled using the Phread scale, which is a negative log scale.

+In other words if *p* is the probability that the nucleotide was incorrectly called, we encode this as *Q* where *Q* = -10 \* log10(*p*).

+

+For example, if *Q* = 30, then *p* = 0.001, a 1-in-1000 chance that the nucleotide is wrong. If *Q* = 20, then *p* = 0.01, a 1-in-100 chance. If *Q* = 10, then *p* = 0.1, a 1-in-10 chance. And so on.

+

+Second, scaled quality values are *rounded* to the nearest integer and encoded using [ASCII printable characters](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ASCII#ASCII_printable_characters). For example, using the Phred33 encoding (which is by far the most common), a *Q* of 30 is encoded as the ASCII character with code 33 + 30 = 63, which is "`?`". A *Q* of 20 is encoded as the ASCII character with code 33 + 20 = 53, which is "`5`". And so on.

+

+Let's define some relevant Python functions:

+

+```python

+def phred33_to_q(qual):

+ """ Turn Phred+33 ASCII-encoded quality into Phred-scaled integer """

+ return ord(qual)-33

+

+def q_to_phred33(Q):

+ """ Turn Phred-scaled integer into Phred+33 ASCII-encoded quality """

+ return chr(Q + 33)

+

+def q_to_p(Q):

+ """ Turn Phred-scaled integer into error probability """

+ return 10.0 ** (-0.1 * Q)

+

+def p_to_q(p):

+ """ Turn error probability into Phred-scaled integer """

+ import math

+ return int(round(-10.0 * math.log10(p)))

+```

+

+

+```python

+# Here are the examples I discussed above

+

+# Convert Qs into ps

+q_to_p(30), q_to_p(20), q_to_p(10)

+```

+

+ (0.001, 0.01, 0.1)

+

+```python=

+p_to_q(0.00011) # note that the result is rounded

+```

+

+ 40

+

+```python=

+q_to_phred33(30), q_to_phred33(20)

+```

+

+ ('?', '5')

+

+To convert an entire string Phred33-encoded quality values into the corresponding *Q* or *p* values, I can do the following:

+

+

+```python

+# Take the first read from the small example above

+name, seq, qual = parse_fastq(StringIO(fastq_string))[0]

+q_string = list(map(phred33_to_q, qual))

+p_string = list(map(q_to_p, q_string))

+print(q_string)

+print(p_string)

+```

+

+ [33, 35, 35, 36, 36, 37, 30, 37, 38, 37, 37, 37, 39, 38, 37, 37, 39, 39, 38, 39, 38, 38, 39, 34, 39, 31, 38, 39, 39, 39, 38, 37, 32, 39, 36, 38, 37, 36, 39, 38, 36, 37, 38, 39, 34, 34, 38, 38, 38, 37]

+ [0.000501187233627272, 0.00031622776601683794, 0.00031622776601683794, 0.00025118864315095795, 0.00025118864315095795, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.001, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.0003981071705534969, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.0007943282347242813, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.000630957344480193, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.00025118864315095795, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.00025118864315095795, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.00025118864315095795, 0.00019952623149688788, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.0001258925411794166, 0.0003981071705534969, 0.0003981071705534969, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.00015848931924611126, 0.00019952623149688788]

+

+

+You might wonder how the sequencer and its software can *know* the probability that a nucleotide is incorrectly called. It can't; this number is just an estimate. To describe exactly how it's estimated is beyond the scope of this notebook; if you're interested, search for academic papers with "base calling" in the title. Here's a helpful [video by Rafa Irizarry](http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eXkjlopwIH4).

+

+A final note: other ways of encoding quality values were proposed and used in the past. For example, Phred64 uses an ASCII offset of 64 instead of 33, and Solexa64 uses "odds" instead of the probability *p*. But Phred33 is by far the most common today and you will likely never have to worry about this.

+

+>A note in map()

+>

+>In Python, the `map()` function is used to apply a given function to all elements of an iterable (such as a list, tuple, or string) and return an iterator (an object that can be iterated, e.g. in a `for`-loop) that yields the results.

+>

+>The `map()` function takes two arguments:

+>

+>A function that is to be applied to each element of the iterable

+>An iterable on which the function is to be applied

+>

+>Here is an example:

+>

+>

+>```python

+># Using a function to square each element of a list

+>numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

+>squared_numbers = map(lambda x: x**2, numbers)

+>print(list(squared_numbers)) # Output: [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

+>```

+>

+>```

+>[1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

+>```

+>

+>In the example above, the `map()` function applies the lambda function `lambda x: x**2` to each element of the numbers list, and returns an iterator of the squared numbers. The `list()` function is used to convert the iterator to a list, so that the result can be printed.

+>

+>Another example is,

+>

+>

+>```python

+># Using the map() function to convert a list of strings to uppercase

+>words = ["hello", "world"]

+>uppercase_words = map(lambda word: word.upper(), words)

+>print(list(uppercase_words)) # Output: ['HELLO', 'WORLD']

+>```

+>

+>```

+>['HELLO', 'WORLD']

+>```

+>

+>It's important to note that the `map()` function returns an iterator, which can be used in a for loop, but is not a list, tuple, or any other iterable. If you want to create a list, tuple, or other iterable from the result of the `map()` function, you can use the `list()`, `tuple()`, or any other built-in function that creates an iterable.

+>

+>In Python 3, the `map()` function returns an iterator, which can be used in a for loop, but it's not iterable. If you want to create a list, tuple, or other iterable from the result of the `map()` function, you can use the `list()`, `tuple()`, or any other built-in function that creates an iterable.

+>

+>In Python 2, `map()` function returns a list, which can be used in a for loop, and it's iterable.

+>

+>In python 3.x, there is an alternative way to use map() function is `list(map(...))` or `tuple(map(...))` etc.

+{: .comment}

+

+## Paired-end reads

+

+Sequencing reads can come in *pairs*. Basically instead of reporting a single snippet of nucleotides from the genome, the sequencer might report a *pair* of

+snippets that appear *close to each other* in the genome. To accomplish this, the sequencer sequences *both ends* of a longer *fragment* of DNA.

+

+Here is simple Python code that mimics how the sequencer obtains one paired-end read:

+

+```python

+# Let's just make a random genome of length 1K

+import random

+random.seed(637485)

+genome = ''.join([random.choice('ACGT') for _ in range(1000)])

+genome

+```

+

+ 'AGTACGTCATACCGTTATGATCTAGGTGGGATCGCGGATTGGTCGTGCAGAATACAGCCTTGGAGAGTGGTTAACACGATAAGGCCGATAATATGTCTGGATAAGCTCAGGCTCTGCTCCGAGGCGCTAAGGTACATGTTATTGATTTGGAGCTCAAAAATTGCCATAGCATGCAATACGCCCGTTGATAGACCACTTGCCTTCAGGGGAGCGTCGCATGTATTGATTGTGTTACATAAACCCTCCCCCCCTACACGTGCTTGTCGACGCGGCACTGGACACTGATACGAGGAGGCACTTCGCTAGAAACGGCTTACTGCAGGTGATAAAATCAACAGATGGCACGCTCGCAACAGAAGCATAATATGCTTCCAACCAGGACCGGCATTTAACTCAATATATTAGCTCTCGAGGACAACGCACTACGTTTTCCAATTCAGCGGACTGGCGCCATTACAGTAAGTTGATTGTGCAGTGGTCTTTGACAGACAGCAGTTCGCTCCTTACTGACAATACCTGATACTTATAGTATGGCAGCGAGTCGTTGTCTAGGTTAGCCACCTCAGTCTACAGCAGGTAATGAAGCATTCCCACAAAGGCTGGTCCATACACCCGACTGCTACGATTCATGCTTCGCTCGAGAACTGCCCCTGCCTTAGATTCCCCCTCGTCTCCAATGAATACCCATTTTTTTAGATTGCTGAAAACCTTTCGTAAGACGCTTTCCAGTGATTACATGCCCTAACTGGGTACAGTTTGCCCAGGAGCTTTTTGGATGGAGGAGTATTAGTAGCGACCAAAACTCTTCCTCGACTGTTACTGTGTAGAGTCCCAAACGCTAAAGCGGTCCCAGAAAAACGGAACGGCCTACAGATTAAATTGCTCCGTGTTGCAGTTAAGGCGTACAAACCCCTCTGTGTATTAGTTTAAGTCTCTGAGTCTTCTTTGCTATGACGGATTGATGGGTGCCGGTTTGTAGTTCAAGAACCGTGAGTGAACC'

+

+```python

+# The sequencer draws a fragment from the genome of length, say, 250

+offset = random.randint(0, len(genome) - 250)

+fragment = genome[offset:offset+250]

+fragment

+```

+

+ 'GTATTGATTGTGTTACATAAACCCTCCCCCCCTACACGTGCTTGTCGACGCGGCACTGGACACTGATACGAGGAGGCACTTCGCTAGAAACGGCTTACTGCAGGTGATAAAATCAACAGATGGCACGCTCGCAACAGAAGCATAATATGCTTCCAACCAGGACCGGCATTTAACTCAATATATTAGCTCTCGAGGACAACGCACTACGTTTTCCAATTCAGCGGACTGGCGCCATTACAGTAAGTTGATT'

+

+```python

+# Then it reads sequences from either end of the fragment

+end1, end2 = fragment[:75], fragment[-75:]

+end1, end2

+```

+

+ ('GTATTGATTGTGTTACATAAACCCTCCCCCCCTACACGTGCTTGTCGACGCGGCACTGGACACTGATACGAGGAG',

+ 'CAATATATTAGCTCTCGAGGACAACGCACTACGTTTTCCAATTCAGCGGACTGGCGCCATTACAGTAAGTTGATT')

+

+```python

+# And because of how Illumina sequencing works, the

+# second end is always from the opposite strand from the first

+# (this is not the case for 454 and SOLiD data)

+

+import string

+

+# function for reverse-complementing

+revcomp_trans = str.maketrans("ACGTacgt", "TGCAtgca")

+def reverse_complement(s):

+ return s[::-1].translate(revcomp_trans)

+

+end2 = reverse_complement(end2)

+end1, end2

+```

+

+ ('GTATTGATTGTGTTACATAAACCCTCCCCCCCTACACGTGCTTGTCGACGCGGCACTGGACACTGATACGAGGAG',

+ 'AATCAACTTACTGTAATGGCGCCAGTCCGCTGAATTGGAAAACGTAGTGCGTTGTCCTCGAGAGCTAATATATTG')

+

+FASTQ can be used to store paired-end reads. Say we have 1000 paired-end reads. We should store them in a *pair* of FASTQ files. The first FASTQ file (say, `reads_1.fq`) would contain all of the first ends and the second FASTQ file (say, `reads_2.fq`) would contain all of the second ends. In both files, the ends would appear in corresponding order. That is, the first entry in `reads_1.fq` is paired with the first entry in `reads_2.fq` and so on.

+

+Here is a Python function that parses a pair of files containing paired-end reads.

+

+```python

+def parse_paired_fastq(fh1, fh2):

+ """ Parse paired-end reads from a pair of FASTQ filehandles

+ For each pair, we return a name, the nucleotide string

+ for the first end, the quality string for the first end,

+ the nucleotide string for the second end, and the

+ quality string for the second end. """

+ reads = []

+ while True:

+ first_line_1, first_line_2 = fh1.readline(), fh2.readline()

+ if len(first_line_1) == 0:

+ break # end of file

+ name_1, name_2 = first_line_1[1:].rstrip(), first_line_2[1:].rstrip()

+ seq_1, seq_2 = fh1.readline().rstrip(), fh2.readline().rstrip()

+ fh1.readline() # ignore line starting with +

+ fh2.readline() # ignore line starting with +

+ qual_1, qual_2 = fh1.readline().rstrip(), fh2.readline().rstrip()

+ reads.append(((name_1, seq_1, qual_1), (name_2, seq_2, qual_2)))

+ return reads

+

+fastq_string1 = '''@509.6.64.20524.149722/1

+AGCTCTGGTGACCCATGGGCAGCTGCTAGGGAGCCTTCTCTCCACCCTGA

++

+HHHHHHHGHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHIIHHIHFHHF

+@509.4.62.19231.2763/1

+GTTGATAAGCAAGCATCTCATTTTGTGCATATACCTGGTCTTTCGTATTC

++

+HHHHHHHHHHHHHHEHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHDHHHHHHGHGHH'''

+

+fastq_string2 = '''@509.6.64.20524.149722/2

+TAAGTCAGGATACTTTCCCATATCCCAGCCCTGCTCCNTCTTTAAATAAT

++

+HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH@HHFHHHEFHHHHHHFF#FFFFFFFHHHHH

+@509.4.62.19231.2763/2

+CTCTGCTGGTATGGTTGACGCCGGATTTGAGAATCAANAAGAGCTTACTA

++

+HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHEHEHHHFHGHHHHHHHH>@#@=44465HHHHH'''

+

+parse_paired_fastq(StringIO(fastq_string1), StringIO(fastq_string2))

+```

+

+ [(('509.6.64.20524.149722/1',

+ 'AGCTCTGGTGACCCATGGGCAGCTGCTAGGGAGCCTTCTCTCCACCCTGA',

+ 'HHHHHHHGHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHIIHHIHFHHF'),

+ ('509.6.64.20524.149722/2',

+ 'TAAGTCAGGATACTTTCCCATATCCCAGCCCTGCTCCNTCTTTAAATAAT',

+ 'HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH@HHFHHHEFHHHHHHFF#FFFFFFFHHHHH')),

+ (('509.4.62.19231.2763/1',

+ 'GTTGATAAGCAAGCATCTCATTTTGTGCATATACCTGGTCTTTCGTATTC',

+ 'HHHHHHHHHHHHHHEHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHDHHHHHHGHGHH'),

+ ('509.4.62.19231.2763/2',

+ 'CTCTGCTGGTATGGTTGACGCCGGATTTGAGAATCAANAAGAGCTTACTA',

+ 'HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHEHEHHHFHGHHHHHHHH>@#@=44465HHHHH'))]

+

+>A note on triple quotes

+>

+>In Python, triple quotes (either single or double) are used to create multi-line strings. They can also be used to create doc-strings, which are used to document a function, class, or module.

+>

+>For example:

+>

+>

+>```python

+>string1 = """This is a

+>multiline string"""

+>

+>string2 = '''This is also

+>a multiline string'''

+>

+>print(string1)

+># Output:

+># This is a

+># multiline string

+>

+>print(string2)

+># Output:

+># This is also

+># a multiline string

+>```

+>

+> This is a

+> multiline string

+> This is also

+> a multiline string

+>

+>

+>Triple quotes can also be used to create docstrings, which are used to document a function, class, or module. The first line of a docstring is a brief summary of what the function, class, or module does, and the following lines provide more detailed information.

+>

+>

+>```python

+>def my_function():

+> """

+> This is a docstring for the my_function.

+> This function does not perform any operation.

+> """

+> pass

+>

+>print(my_function.__doc__)

+># Output:

+># This is a docstring for the my_function.

+># This function does not perform any operation.

+>```

+>

+>

+> This is a docstring for the my_function.

+> This function does not perform any operation.

+>

+{: .comment}

+

+## How good are my reads?

+

+Let's reuse the `parse_fastq` function from above:

+

+

+```python

+reads = parse_fastq(StringIO(fastq_string))

+```

+

+```python

+run_qualities = []

+for read in reads:

+ read_qualities = []

+ for quality in read[2]:

+ read_qualities.append(phred33_to_q(quality))

+ run_qualities.append(read_qualities)

+```

+

+```python

+base_qualities = []

+for i in range(len(run_qualities[0])):

+ base = []

+ for read in run_qualities:

+ base.append(read[i])

+ base_qualities.append(base)

+

+# same thing with numpy

+# base_qualities = np.array(run_qualities).T

+```

+

+

+```python

+import numpy as np

+

+plotting_data = {

+ 'base':[],

+ 'mean':[],

+ 'median':[],

+ 'q25':[],

+ 'q75':[],

+ 'min':[],

+ 'max':[]

+}

+for i,base in enumerate(base_qualities):

+ plotting_data['base'].append(i)

+ plotting_data['mean'].append(np.mean(base))

+ plotting_data['median'].append(np.median(base))

+ plotting_data['q25'].append(np.quantile(base,.25))

+ plotting_data['q75'].append(np.quantile(base,.75))

+ plotting_data['min'].append(np.min(base))

+ plotting_data['max'].append(np.max(base))

+```

+

+

+```python

+import pandas as pd

+plotting_data_df = pd.DataFrame(plotting_data)

+```

+

+

+```python

+import altair as alt

+

+base = alt.Chart(plotting_data_df).encode(

+ alt.X('base:Q', title="Position in the read")

+).properties(

+ width=800,

+ height=200)

+

+median = base.mark_tick(color='red',orient='horizontal').encode(

+ alt.Y('median:Q', title="Phred quality score"),

+)

+

+q = base.mark_rule(color='green',opacity=.5,strokeWidth=10).encode(

+ alt.Y('q25:Q'),

+ alt.Y2('q75:Q')

+)

+

+min_max = base.mark_rule(color='black').encode(

+ alt.Y('min:Q'),

+ alt.Y2('max:Q')

+)

+

+median + q + min_max

+```

+

+

+

+## Other comments

+

+In all the examples above, the reads in the FASTQ file are all the same length. This is not necessarily the case though it is usually true for datasets generated by sequencing-by-synthesis instruments. FASTQ files can contain reads of various lengths.

+

+FASTQ files often have the extension `.fastq` or `.fq`.

+

+## Other resources

+

+- [BioPython](http://biopython.org/wiki/Main_Page)

+- [SeqIO](http://biopython.org/wiki/SeqIO)

+- [SAMtools](http://samtools.sourceforge.net/)

+- [FASTX](http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/)

+- [FASTQC](http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/)

+- [seqtk](https://github.com/lh3/seqtk)

+