by Lev Lafayette

ISBN-10: 0-9943373-1-0

ISBN-13: 978-0-9943373-1-3

Sequential and Parallel Programming with C and Fortran by Lev Lafayette, 2015, 2020

Published by the Victorian Partnership for Advanced Computing (trading as V3 Alliance) .

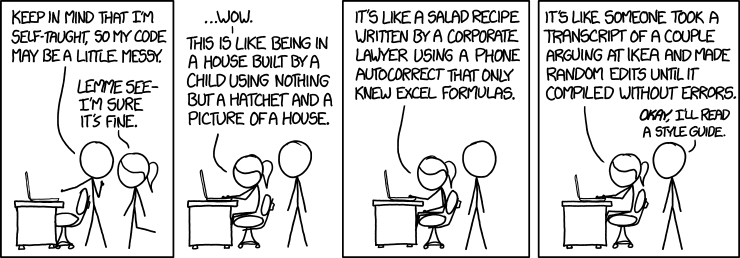

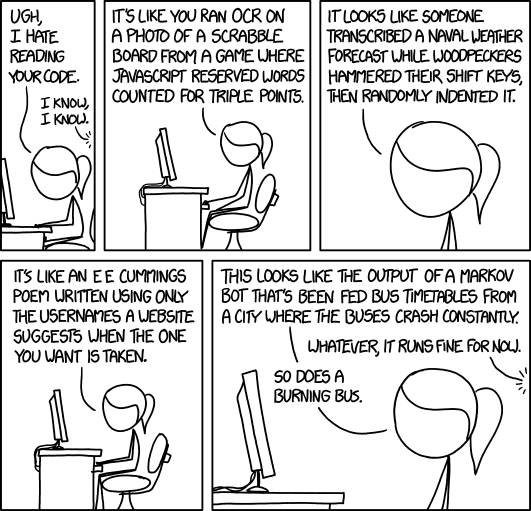

Cover art composed by Michael D'Silva, featuring several clusters operated by the Victorian Partnership for Advanced Computing. Middle image (Trifid) by Craig West. Other images from Chris Samuel, et. al. from VPAC and Randall Munroe (under license, see: https://xkcd.com/license.html).

Sequential and Parallel Programming with C and Fortran, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

All trademarks are property of their respective owners.

0.0 Introduction 0.1 Foreward 0.1 Preface

1.0 Current Trends in Computer Systems 1.1 Computer System Architectures 1.2 Processors, Cores, and Threads 1.3 Multithreaded Applications 1.4 Hardware Advanced 1.5 Parallel Processing Performance and Optimisation 1.6 Programming Practises

2.0 Sequential Programming with C and Fortran 2.1 Fortran and C Fundamentals 2.2 Program and Compilation 2.3 Variables and Constants 2.4 Data Types and Operations 2.5 Loops and Branches 2.6 Data Structures 2.7 Input and Output

3.0 Parallel Programming with OpenMP 3.1 Shared Memory Concepts 3.2 Directives and Internal Control Variables 3.3 Work Sharing and Task Constructs 3.4 Tasks and Synchronisation 3.5 Targets and Teams 3.6 Reductions, Combination, and Summary 3.7 POSIX Threads Programming

4.0 Parallel Programming with OpenMPI 4.1 Distributed Memory Concepts 4.2 Program Structure and OpenMPI Wrappers 4.3 Basic Routines 4.4 Datatypes 4.5 Extended Communications and Other Routines 4.6 Compiler Differences 4.7 Collective Communications

5.0 GPGPU Programming 5.1 GPGPU Technology 5.2 OpenACC Directives 5.3 CUDA Programming 5.4 OpenCL Programming

6.0 Profiling and Debugging 6.1 Testing Approaches 6.2 Profiling with Grof, TAU and PDT 6.3 Memory Checking with Valgrind 6.4 Debugging with GDB

7.0 References

It is finally time for a book like this one.

When parallel programming was just getting off the ground in the late 1960s, it started as a battle between starry-eyed academics who envisioned how fast and wonderful it could be, and cynical hard-nosed executives of computer companies who joked that “parallel computing is the wave of the future, and always will be.”

The pivotal example of this was the 1967 debate between Dan Slotnick (who spearheaded the experimental 64-processor ILLIAC IV at the University of Illinois) and Gene Amdahl (architect of the IBM System 360 line of mainframes). Amdahl’s argument against parallel processing was devastating and was quickly embraced by an industry that dreaded the idea that they might have to rewrite millions of lines of software, retrain an entire generation of programmers and hardware designers, and backpedal on decades of hard-won experience with the traditional serial computing model: One memory, one processor, one instruction at a time.

Yet, the ILLIAC IV was a successful machine. It was the fastest supercomputer in the world for an unusually long time. Believers in parallel programming formed a cult-like community of true believers for whom “Amdahl’s law”, as William Ware described it, was a constant thorn in their side.

By the early 1980s, Seymour Cray was pushing against the limits of the laws of physics to support the serial programming model with his vector mainframes, and he ultimately reached the point where it was clear Cray Research Inc. would have to expose the programmer to a modest amount of parallelism, like two or four processors coordinated to run a single job. A Cray Research company executive said, unaware of the irony of his statement, “We want to get into parallel processing, but we want to do it one step at a time.”

Universities were less conservative about parallel programming. After the ILLIAC, the University of Illinois showed how a shared memory computer with many processors (CEDAR) could be built and programmed with the help of a sophisticated compiler. Caltech showed that a distributed memory system could be built by interconnecting a desktop full of personal computer parts (the Cosmic Cube) and programmed by passing messages between each PC-like computing node.

Smaller companies became infected with the vision of the academics regarding parallel processing. They included FPS, Denelcor, Alliant, Thinking Machines, and nCUBE. My own experiences at FPS and nCUBE led to a formulation of the counter-argument to Amdahl’s law that bears my name, but is really nothing more than the common-sense observation that problem sizes increase to match the computing power available, so the serial bottleneck actually shrinks instead of staying constant. That simple observation countered, at last, those who had been using Amdahl’s law to defend as scientific what really was an emotion-driven trepidation regarding parallel programming. In a very short time, IBM, Digital Equipment, Cray, and other giants in the computing industry announced plans for parallel computing products as contrasted with research projects. It was no longer the province of risky startup ventures; by 1990, parallel computing had become mainstream.

We are now in the "late adopters" stage of the technology adoption cycle laid out by Geoffrey A. Moore in his classic, Crossing the Chasm. The dust has settled on the field of parallel programming to the point that we now have community standards for parallel programming environments. Many independent software vendors ship software designed for massively parallel computer clusters in data centers. Universities routinely teach parallel programming as part of an undergraduate computer science curriculum. In a way, the war is over, and parallel programming won. But now comes Reconstruction, and that stage of the war is going very slowly. That is why this book is timely.

A technology director for the National Security Agency informed me that only about five percent of their army of programmers knows how to program in parallel. One reason that agency went after the Unified Parallel C model was that it seemed to raise, rather easily, the fraction of parallel-literate programmers to fifteen percent. A little effort went a long way, tripling their human resources for truly high-performance computing tasks.

Sequential and Parallel Programming with C and Fortran is exactly the right book to bring people up to speed with minimum discomfort, and with a choice of topics that will not soon go out of date. The MPI Standard presented in the book is the outgrowth of Caltech’s Cosmic Cube. Similarly, the OpenMP Standard explained here is the outgrowth of the CEDAR project of the University of Illinois. Those standards are here to stay, just as languages like Fortran and C are not likely to be completely displaced anytime soon; they absorbed new ideas throughout their history, incorporating them into revised standard definitions of their language.

The models for shared and distributed memory programming have similarly stabilized and rallied around OpenMP and MPI, so they, too, absorb new ideas as tweaks to a well-established standard. In other words, the thinking has finally converged in a part of computing technology that was once an extremely unsettled set of schools of thought that definitely did not work and play well together.

Lev Lafayette approaches the subject with just the right touch of Australian levity, increasing the readability of an admittedly dry topic. He judiciously chooses the right amount of detail to cover the maximum amount of material in the smallest number of pages, imitating the classic Kernighan and Ritchie book that introduced the C language to a generation of programmers. Instead of listing the strict grammar rules, the author gives pointer about how you should write programs, the guidelines of style and clarity that are absent from a User’s Manual. If you only have time to read one book about parallel computing, this is it.

John L. Gustafson

In many ways contemporary computing is an elaboration of mechanical automation and calculation, whose origins can date back at least to the Antikythera mechanism, from approximately 150 to 100 BCE, and was used for astronomical positions and calendaring. From there multiple chains of inquiry can be traced to the development of programmable automata, the feedback mechanism for sails on windmills, centrifugal governor originally for mills and steam engines, the Jacquard loom's logic board, and Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine. The honour of the first real programmer goes to Ada Lovelace, who theorised that the Analytical Engine could engage in logical computation of symbols as well as numbers and wrote the first program which calculated a sequence of Bernoulli numbers.

As the theoretical understanding of control theory was developed alongside relay logic and industrial electrification, telephony and switching fabrics underwent massive improvements in the twentieth century CE, which continues today. In the field of programming, this correlates with the development of punched "Hollerith cards" to provide pre-programmed instructions to tabulating machines, The invention of von Neumann architecture which allowed instructions to be stored in computer memory, and the development of programming languages from individual machine code, to assembly languages, to higher level languages such as FORTRAN (1954) and C (1972).

But in all of these cases, the logic and feedback mechanisms assumes sequential processing. This, of course, is perfectly in accord with the "time's arrow", as Arthur Eddington pithily described the assymetrical "one way property of time that has no analogue in space" (The Nature of the Physical World, 1928). The traditional, sequential, model of a program is to break down a problem into a discrete set of instructions, and to execute those instructions in turn. In terms of computational architecture, this would be carried out on one processor.

Sequential programming is, of course, an incredibly important technological development for the species. However it does run into two major scalability issues. The first is a time-based limitation; if compute resources are available to conduct parallel processing it is inefficient to conduct them in sequence. The second is a task-based limitation; so many computational tasks are based on simulations of a parallel system, because so much of reality is a parallel system. Parallel programming extensions to sequential programming provides the opportunity to save time, solve more complex problems, and, in some cases, take advantage of distributed compute resources.

Fortunately, computational resources are now available to carry out parallel programming. This consists of developments in the traditional two areas of computing, hardware and software. From a hardware perspective, contemporary computer systems are almost invariably multicore and multiprocessor devices, and many of them are connected, whether through tight-coupling (e.g., clusters) or loosely-coupled (e.g., grids). From a software perspective a variety of tools exist that can treat multiple processors in a single system, whether it is through distributed and grid system (such as the @home projects, folding@home, seti@home etc), whether it is through thread-based parallelism, or whether it is through message passing paradigms.

This book is designed as a strong introduction to parallel programming and is primarily for people who have had some programming experience, particularly with C and Fortran. Designed as both a reference and a self-teaching guide, it begins with an exploration of computer architecture and contemporary trends that have lead to the increasing importance of parallel computation, along with potential limitations and implementations. In many ways this is the most time-dependent chapter of the book, due to the particulars of technological change.

Following this, the book provides a summary of some core sequential programming aspects in the C and Fortran programming languages, including a review of their fundamental structures, the use of variables, loops, conditional branching, along with various routines and data structures. For those who have a good grounding in either or both of these languages this will be very familiar territory. Whilst it is not meant to be even remotely an in-depth study in either language, it does contain a lot of advice for good programming practice, which is not just relevant for sequential programming, but especially also for shared and distributed parallel programming.

One particular type of parallellism is the shared memory, multi-threaded approach. The most well-known implementation of this approach is the OpenMP (Open Multi-Processing) application programming interface, and is explored here. The relevant chapter covers the conceptual level of the OpenMP programming, especially the fork-join and work-sharing models, an elaboration on the various directives to include synchronisation and data scope issues, along with run-time libraries and routines and environment variables.

Moving from shared memory to parallel programming involves a conceptual change from multi-threaded programming to a message passing paradigm. In this case, MPI (Message Passing Interface) is one of the most popular standards and is used here, along with an implementation as OpenMPI. In this chapter core routines for establishing and closing communications worlds are explored, along with interprocess communication, and then collective communications, before concluding with multiple communication worlds.

The introduction of using graphics-processing units (GPU) for general purpose computational problems (GPGPUs) is an exciting development in parallel processing. Although only capable of a smaller subset of parallel problems and currently with a moderate memory cache, the exceptional performance of GPUs comes from their "closeness" of the cores to each other. This book provides an introduction to the technology, lower-entry OpenACC pragma-driven programming, and CUDA programming.

Finally, relevant to sequential, multi-threaded, and message passing programs, is the issues of profiling and debugging. In particular the applications TAU (Tuning and Analysis Utilities), Valgrind, and GDB (GNU Debugger) are explored in some detail with some practical examples on how to improve one's code.

As a whole it must be reiterated that this book gives but a broad introduction to the subjects in question. There are, of course, some very detailed books on each of the subjects addressed; books on multicore systems, books on Fortran, books on C, books on OpenMP, MPI, debugging and profiling. Designed as two-days of learning material, this is no substitute for the thousands of pages of material that in-depth study can provide on each subject.

As with other books recently published in this series it is designed in part as a quick reference guide for research-programmers and as a workbook, which can be studied from beginning to end. Indeed, it is in the latter manner than a great deal of the material has been derived from a number of parallel programming courses conducted by the Victorian Partnership for Advanced Computing (VPAC). The content is deliberately designed in a structured manner, and as such can be used by an educator, including those engaging in self-education. Whether through instruction or self-learning it is highly recommended that a learner take the time to work through the code examples carefully and to be prepared to make plenty of errors. Errors are a very effective learning tool.

A number of sources directly contributed to this book, most obviously the official documentation for the OpenMPI API (OpenMP Application Programming Interface v4.0.2, 2015 and OpenMP Application Programming Interface Examples v4.5, 2015), the Open MPI implementation (Open MPI User Manual, 2013), the various debugging and profiling tools (e.g., TAU User Guide, 2015, Valgrind User Manual, 2015, Debugging with GDB, 2015). Credit must also be given to the influence of some timeless classics in the programming world, such as George Pólya, How to Solve It (1945), Brian W. Kernighan and P. J. Plauger, The Elements of Programming Style (2nd edition, 1978), Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie, The C Programming Language, (1978), Niklas Wirth Algorithms and Data Structures (1985), Michael Metcalf and John Reid, Fortran 90/95 Explained (1996), and Andy Oram, Greg Wilson (eds), Beautiful Code (2007).

Recognition is also given to the various training manuals produced at the Victorian Partnership for Advanced Computing over the years, and those from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the Edinburg Parallel Computing Centre. From the latter two the material (Parallel Programming, OpenMP, Message Passing Interface) all by Blaise Barney, are exceptional contributions to the field as is the course material from Elspeth Minty et. al., (Decomposing the Potentially Parallel, Writing Message Passing Programs with MPI). From the former, special thanks is given to Bill Applebe, Alan Lo, Steve Quenette, Patrick Sunter, and Craig West.

I also wish to thank Matt Davis who reviewed this manuscript and publication prior to publication and for their excellent advice. All errors and omissions are my own.

Thanks are also given to the Victorian Partnership of Advanced Computing for the time and resources necessary for the publication of this book, and especially Bill Yeadon, manager of research and development, and Ann Borda, CEO, who authorised its publication.

This book is part of a series designed to assist researchers, systems administrators, and managers in a variety of advanced computational tasks. Other books that will be published in this series include: Supercomputing with Linux., Mathematical Applications and Programming., Data Management Tools for eResearchers., Building HPC Clusters and Clouds., Teaching Research Computing to Advanced Learners., Quality Assurance in Technical Organisations., Technical Project Management, and A History of the Victorian Partnership of Advanced Computing.

Lev Lafayette, Victorian Partnership for Advanced Computing, Melbourne

High performance computing (HPC) is the use of supercomputers and clusters to solve advanced computation problems. All supercomputers, a nebulous term for computer that is at the forefront of current processing capacity, in contemporary times use parallel computing, the distribution of jobs or processes over one or more processors and by splitting up the task between them.

It is possible to illustrate the degree and development of parallelisation by using Michael Flynn's Taxonomy of Computer Systems (1966), where each process is considered as the execution of a pool of instructions (instruction stream) on a pool of data (data stream).

From this complex is four basic possibilities:

- Single Instruction Stream, Single Data Stream (SISD)

- Single Instruction Stream, Multiple Data Streams (SIMD)

- Multiple Instruction Streams, Single Data Stream (MISD)

- Multiple Instruction Streams, Multiple Data Streams (MIMD)

As computing technology has moved increasingly to the MIMD taxonomic classification additional categories have been added:

- Single program, multiple data streams (SPMD)

- Multiple program, multiple data streams (MPMD)

Single Instruction Stream, Single Data Streams (SISD)

This is the simplest and, up until the end of the 20th century, the most common processor architecture on desktop computer systems, and if often referred to as a traditional von Neumman architecture. Also known as a uniprocessor system it offers a single instruction stream and a single data stream. Whilst uniprocessor systems were not able to run programs in parallel (i.e., multiple tasks simultaneously), they were able or include concurrency (i.e., multiple logical tasks) through a number of different methods:

a) It is possible for a uniprocessor system to run processes concurrently by switching between one and another.

b) Superscale instruction level parallelism could be used on uniprocessors. More than one instruction during a clock cycle is simultaneously dispatched to different functional units on the processor.

c) Instruction prefetch, where an instruction is requested from main memory before it is actually needed and placed in a cache. This often also includes a prediction algorithm of what the instruction will be.

d) Pipelines, on the instruction level or the graphics level, can also serve as an example of concurrent activity. An instruction pipeline (e.g., RISC) allows multiple instructions on the same circuitry by dividing the task into stages. A graphics pipeline implements different stages of rendering operations to different arithmetic units.

Single Instruction Stream, Multiple Data Streams (SIMD)

SIMD architecture represents a situation where a single processor performs the same instruction on multiple data streams and are described as a type of "data level parallelism". This commonly occurs in contemporary multimedia processors, for example MMX instruction set from the 1990s, which lead to Motorolla's PowerPC Altivec, and more contemporary times AVE (Advanced Vector Extensions) instruction set used in Intel Sandy Bridge processors and AMD's Bulldozer processor. These developments have primarily been orientated towards real-time graphics, using short-vectors. Contemporary supercomputers are invariably MIMD clusters which can implement short-vector SIMD instructions. IBM is still continuing with a general SIMD architecture through their Power Architecture.

SIMD was also used especially in the 1970s and notably on the various Cray systems. For example the Cray-1 (1976) had eight "vector registers," which held sixty-four 64-bit words each (long vectors) with instructions applied to the registers. Pipeline parallelism was used to implement vector instructions with separate pipelines for different instructions, which themselves could be run in batch and pipelined (vector chaining). As a result the Cray-1 could have a peak performance of 240 MFLOPS - extraordinary for the day, and even acceptable in the early 2000s.

SIMD is also known as vector processing or data parallelism, in comparison to a regular SIMD CPU which operates on scalars. SIMD lines up a row of scalar data (of uniform type) as a vector and operates on it as a unit. For example, inverting an RGB picture to produce its negative, or to alter its brightness etc. Without SIMD each pixel would have to be fetched to memory, the instruction applied to it, and then returned. With SIMD the same instruction is applied to all the data, depending on the availability of cores, e.g., get n pixels, apply instruction, return. The main disadvantages of SIMD, within the limitations of the process itself, is that it does require additional register, power consumption, and heat.

Multiple Instruction Streams, Single Data Stream (MISD)

Multiple Instruction, Single Data (MISD) occurs when different operations are performed on the same data. This is quite rare and indeed debatable as it is reasonable to claim that once an instruction has been performed on the data, it's not the same anymore. If one allows for a variety of instructions to be applied to the same data which can change, then various pipeline architectures can be considered MISD.

Systolic arrays are another form of MISD. They are different to pipelines because they have a non-linear array structure, they have multidirectional data flow, and each processing element may even have its own local memory . In this situation, a matrix pipe network arrangement of processing units will compute data and store independently of each other. Matrix multiplication is an example of such an array in an algorithmic form, where once a matric is introduced one row at a time from the top of the array, whereas another matrix is introduced one column at a time.

MISD machines are rare; the Cisco PXF processor is an example. They can be fast and scalable, as they do operate in parallel, but they are really difficult to build. Another well-known examples was the Space Shuttle flight control computer.

Multiple Instruction Streams, Multiple Data Streams (MIMD)

Multiple Instruction, Multiple Data (MIMD) have independent and asynchronous processes that can operate on a number of different data streams. They are now the mainstream in contemporary computer systems and thus can be further differentiated between multiprocessor computers and their extension, multicomputer mutiprocessors. As the name clearly indicates, the former refers to single machines which have multiple processors and the latter to a cluster of these machines acting as a single entity.

Multiprocessor systems can be differentiated between shared memory and distributed memory. Shared memory systems have all processors connected to a single pool of global memory (whether by hardware or by software). This may be easier to program, but it's harder to achieve scalability. Such an architecture is quite common in single system unit multiprocessor machines.

With distributed memory systems, each processor has its own memory. Finally, another combination is distributed shared memory, where the (physically separate) memories can be addressed as one (logically shared) address space. A variant combined method is to have shared memory within each multiprocessor node, and distributed between them.

Parallel Operations in SIMD

There is particular architecture that includes instructions explicitly intended to perform parallel operations across data that is stored in the independent subwords or fields of a register. This is known as "SIMD within a register" or SWAR. Whilst previously existing in assembly code, it was introduced as multimedia extension in 1996 for desktop systems with Intel's MMX Multimedia Instruction Set Extensions. Following MMX there were also SWAR implementations for the Digital Alpha MAX (MultimediA eXtensions), Hewlett-Packard's PA-RISC MAX (Multimedia Acceleration eXtensions), MIPS MDMX (Digital Media eXtension, which came with the charming pronunciation "Mad Max"), and the Sun SPARC V9 VIS (Visual Instruction Set). These instruction set extensions, whilst comparable, are incompatible.

Divisions within MIMD

More recently further subdivisions within that category are considered. Specifically there are the taxons of Single Program Multiple Data streams (SPMD) and Multiple Programs Multiple Data streams (MPMD). These classifications have gained recent popularity given the widespread use of MIMD systems.

In the former case (SPMD), multiple autonomous processors execute the same program on multiple data streams. This differs from SIMD approaches which a single processor executes on multiple data streams and as a result each processor executing SPMD code may have a different control flow path through the program.

In the latter case (MPMD) the autonomous processors operate with at least two independent programs.

Other classifications

Another architecture approach was developed by Tse-yun Feng. For Feng, the degree of parallelism was important, based on on the maximum number of bits that could be processed in unit time. The degree of parallelism is how many operations can be executed simultaneously.

Multiple tests will generate an average degree of parallelism. Feng classified systems into four types according to the bit and word, sequential and parallel. This leads to the following system descriptions:

Word serial bit serial (WSBS): One bit of one selected word is processed at a time.

Word serial bit parallel (WSBP): One word of n bit is processed at a time (aka Word Slice processing).

Word parallel bit serial (WPBS): One bit from all words are processed at a time (aka Bit Slice processing)

Word parallel bit parallel (WPBP): All bits from all words are processed at unit time. This is maximum parallelism.

A further development occurred in 1977 by Wolfgang Handler which proposed a schema known as the Erlangen Classification System, based on system units and pipelining. A computer is described by the number of processor control units (K), the number of arithmetic logic units or processing elements under the control of one PCU (D), the word length of an ALU or PE (W), the number of PCUs that can be pipelined (K'), the number of ALUs that can be pipelined (D') and the number of pipelined stages on all ALUs or in a single PE. (W').

Hence the parallelism is expressed using a triplet containing the six values.

ComputerType = (k [* k'], d [* d'], w [* w'])

There are also connection operators to represent inhomogeneous additional units (+), operating modes (v) and macropipelining (x).

Uni- and Multi-Processors

A further distinction needs to be made between processors and cores. A processor is a physical device that accepts data as input and provides results as output. A uniprocessor system has one such device, although the definitions can become ambiguous. In some uniprocessor systems it is possible that there is more than one, but the entities engage in separate functions. For example, a computer system that has one central processing unit may also have a co-processor for mathematic functions and a graphics processor on a separate card. Is that system uniprocessor? Arguably not as the co-processor will be seen as belonging to the same entity as the CPU, and the graphics processor will have different memory, system I/O, and will be dealing with different peripherals. In contrast a multiprocessor system does share memory, system I/O, and peripherals. But then the debate will become murky with the distinction between shared and distributed memory discussed above.

Uni- and Multi-core

In addition to the distinction between uniprocessor and multiprocessor there is also the distinction between unicore and multicore processors. A unicore processor carries out the usual functions of a CPU, according to the instruction set; data handling instructions (set register values, move data, read and write), arithmetic and logic functions (add, subtract, multiply, divide, bitwise operations for conjunction and disjunction, negate, compare), and control-flow functions (conditionally branch to another address within a program, indirectly branch and return). A multicore processor carries out the same functions, but with independent central processing units (note lower case) called 'cores'. Manufacturers integrate the multiple cores onto a single integrated circuit die or onto multiple dies in a single chip package.

In terms of theoretical architecture, a uniprocessor system could be multicore, and a multiprocessor system could be unicore. In practise the most common contemporary architecture is multiprocessor and multicore. The number of cores is represented by a prefix. For example, a dual-core processor has two cores (e.g. AMD Phenom II X2, Intel Core Duo), a quad-core processor contains four cores (e.g. AMD Phenom II X4, Intel i3, i5, and i7), a hexa-core processor contains six cores (e.g. AMD Phenom II X6, Intel Core i7 Extreme Edition 980X), an octo-core processor or octa-core processor contains eight cores (e.g. Intel Xeon E7-2820, AMD FX-8350) etc.

GPUs

A Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) is a particular type of multicore processor which was originally designed, as the name suggests, the maniplation of images. The architecture of such devices, which heavily involve matrix and vector calculations, makes them particularly suitable for certain non-graphics computations of the "pleasingly parallel" variety, especially of the SIMD/SPMD variety. In these cases the GPU is known as a GPGPU, or general purpose computing on a GPU.

In terms of hardware the main GPUs at this time include the Radeon HD 7000 series and those based on the Maxwell microarchitecture. The NVIDIA GM200 GPU, for example, has some 3072 CUDA cores. This obviously is a lot more than CPU processor cores, however there are two main caveats to keep in mind here. Firstly, the CUDA cores are quite limited in their processor memory compared to CPUs, and secondly their clock speed (at 988 MHz base) is significantly lower. GPUs are an absolutely exceptional tool if one has a lot of small datasets that need processing.

Uni- and Mult-Threading

In addition to the distinctions between processors and cores, whether uni- or multi-, there is also the question of threads and its distinction from a process. A process provides the resources to execute an instance of a program (such as address space, the code, handles to system objects, a process identifier etc). An execution thread is the smallest processing unit in an operating system, contained inside a process. Multiple threads can exist within the same process and share the resources allocated to a process.

On a uniprocessor, multithreading generally occurs by switching between different threads engaging in time-division multiplexing with the processor switching between the different threads, which may give the apperance that the ask is happening at the same time. On a multiprocessor or multi-core system, threads become truly concurrent, with every processor or core executing a separate thread simultaneously.

One form of parallel programming is multithreading, whereby a master thread forks a number of sub-threads and divides tasks between them. The threads will then run concurrently and are then joined at a subsequent point to resume normal serial application.

One implementation of multithreading is OpenMP (Open Multi-Processing). It is an Application Programming Interface (API) that includes language directives for controlling multi-threaded, shared memory parallel programming behaviour. The directives are introduced by the program using a special syntax in the C or Fortran source code. In in a system where OpenMP is not implemented, they would be interpeted as comments.

There is no doubt that OpenMP is an easier form of parallel programming compared to distributed memory parallel programming or directly programming for shared memory using shared memory function calls. However it is limited to a single system unit (no distributed memory) and is thread-based rather than using message passing.

A project worth keeping an eye is Mercury, developed by Dr. Paul Bone at the University of Melbourne. Mercury is a functional programming language which aims to achieve automatic and explicit parallelisation, that is, the code will attempt to parallelise according to the hardware it is runinng on without any pragmas or additional routines. Information is gathered from a profile gathered form a sequential execution of a program which informs the compiler how the program can be paralleslised. In doing so, it also protects from situations where an attempt is made to parallelise, but any potential benefits are lost through overheads and dependencies.

Why Is It A Multicore Future?

Ideally, don't we want clusters of multicore multiprocessors with multithreaded instructions? Of course we do; but think of the heat that this generates, think of the potential for race conditions, such as situations where multiple processes or threads are attemping to read or write to the same resources (e.g., deadlocks, data integrity issues, resource conflicts, interleaved execution issues).

One of the reasons that multicore multiprocessor clusters have become popular is that clock rate has pretty much stalled. Apart from the physical reasons, it is uneconomical. It's simply not worth the cost increasing the frequency of clock rate in terms of the power consumed and the heat dissipitated. Intel calls the rate/heat trade-off a "fundamental theorem of multicore processors". To express simply, the power increases for new processors around around the early to mid 2000s was increasing faster than the performance improvements gained.

The partial solution to the issue was to pipeline power through additional cores, instead of trying to squeeze more and more transistors onto a single processor. As a result, modern processors are made up of multiple cores and system units typically consist of multiple, and often heterogeneous, processors. However this solution requires that programs know how to access and utilise these additional resources.

Very early in computing it was realised that translating instruction and control streams in hardware was significantly more difficult than the datastream memory. Even in the early days of processor designs there was a software and hardware division between the datapath, where numbers were stored and arithmetic was carried out, and control, which sequenced the operations on the datapath. Following von Neumann's (1947) separation of arithmetic logic and control in architecture, Wilkes developed the concept of microprogramming from the realisation that the central processing unit of a computer could be controlled by a miniature, highly specialised computer programs in high-speed ROM. This led to Complex Instruction Set Computer (CISC), as adding instructions was relatively easy in microcode compared to hardwiring, and rapid advances in metal–oxide–silicon (MOS) transistors fuelled competition.

Microcode progress was particularly rapid in the 1970s, following the advances in MOS transistors and occurred in parallel to the developments in minicomputers and mainframe instruction set architecture, which led to a highly competitive environment in processors and assembly language programming. A very significant contribution was the the Intel 4004, the first single-chip microprocessor, released in 1971. Early microprocessor integrated circuits contained only the processor development led to chips containing more of internal electronic parts of a computer, including the CPU, ROM, on-chip RAM, and I/O. The VAX line of computers developed by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) especially with processors like the MicroVAX II's 78032 which was the first microprocessor with an on-board memory management unit. It was the microprocessor that allowed for the development of microcomputers, which were affordable to small business and individuals, ushering in a personal computer revolution in the 1980s and 1990s.

In the first decade of the 21st century multi-core CPUs became commercially available, spurred by research into multi-core processors and parallel computing. In 2009 Intel released the Single-Chip Cloud Computing processor as an example, with 48 distinct P54C Pentium physical cores connected with a 4×6 2D-mesh on a single chip that communicated through architecture similar to that of a cloud computer data center, hence the name. Another significant contribution was the development of affordable Content-Addressable Memory; this was a form of memory that acts as an associative array, comparing the input search data against a table, and returning the address of the matching data. This helped significantly in the performance of networking devices.

New multicore systems are being developed all the time. Using RISC CPUs, Tilera released 64-core processors in 2007, the TILE64, and in 2011, a one hundred core processor, the Gx100. In 2012 Tilera founder, Dr. Agarwal, was leading a new MIT effort dubbed The Angstrom Project, which was purchased by EZchip superconductor in 2015. It is one of four DARPA-funded efforts aimed at building exascale supercomputers, i.e., a system capable of at least one exaFLOP, or a billion billion calculations per second. The goal is to design a chip with 1,000 cores using a mesh topology.

Certainly, the most exciting development in multicore technology in recent years in GPU technology. Whilst GPUs have been around for a very long time, it is relatively recent that applications have started to be built specifically for this architecture. Sophisticated software often lags behind hardware in this regard. GPUs offer thousands of cores on a single processor, but are only suitable for data or vector parallel computation. GPUs also typically have a significantly lower clock speed and processor memory. It is possible to run a hybrid application that uses CPUs and GPUs, and which uses MPI and the data parallelism of GPUs - but there is likely to be all sorts of bottle-necks due to the different speeds of computation.

Another hardware technology that has recently appeared is the Knight's Landing and the upcoming Knight's Hill Intel's Many Integrated Core microarchitecture from Intel. As implementations of the Xeon Phi, these follow the same general architecture as the x86-64 line whilst sharing some of the characteristics of GPUs, could operate as an independent CPU rather than as an add-on. Knights Landing contains up to 72 cores with four threads per core.

The Problem

The use of multiple processors can improve performance if, and only if, the application or the dataset are capable of being run in parallel, and in reality this means that only part of the application or dataset. This means that one has to identify the portions that can execute simultaneously, which may mean adding parallel extensions to existing code or starting from scratch (the former is usually a more convenient path, which is one of the many reasons why free-and-open-source software is preferred). Because there are numerous limiting factors in this process it is quite possible that for certain tasks that parallelisation can result in lower-than-hoped-for performance and, in some cases, even worse performance than a serial application. How could this be the case? The following examples provide some reasons.

Physical Limits

The physical architecture (see 1.1) can profoundly affect the parallelisation that is available. A system with a single processor is obviously going to be "very limited" in the parallelisation possible, although there is some concurrency that can occur. A system with multiple-processors and multiple cores can potentially having parallelisation, although this will very much depend on the dataset and application. Ultimately however the underlying empirical reality must be respected and given primary recognition. It is no use writing a parallel application for a non-parallel system.

Least this seem obvious one needs to consider not only the architecture of the processor, but also the bandwidth (maximum amount of data that can be transmitted in a unit of time) and latency (minimum time to transmit one object) of the communications network. Latency also includes the software communication overhead. This communication world can apply within a processor or cores, with the CPU and the main memory, CPU and disk, and between different compute nodes. Parallel processing by mounting a datasets stored interstate on the compute nodes is theoretically possible, but not a very good idea (the author has only been asked this once, but it was quite memorable).

Speedup and Locks

Parallel programming and multicore systems should mean better performance. This can be expressed a ratio called speedup (c.f., C. Xavier, S. S. Iyengar, "Introduction to Parallel Algorithms", John Wiley and Sons, 5 Aug. 1998, pp52)

Speedup (p) = Time (serial)/ Time (parallel)

This is varied by the number of processors S = T(1)/T(p), where T(p) represents the execution time taken by the program running on p processors, and T(1) represents the time taken by the best serial implementation of the application measured on one processor.

Linear, or ideal, speedup is when S(p) = p. For example, double the processors resulting in double the speedup.

However parallel programming is hard . More complexity = more bugs. Correctness in parallelisation usually requires synchronisation, of locking is one common implementation. Synchronisation and atomic operations causes loss of performance, communication latency as they effectively make a portion of the program serial. A probable issue in parallel computing is deadlocks, where two or more competing actions are each waiting for the other to finish, and thus neither ever does. An apocryphal story of a Kansas railroad statue radically illustrates the problem of a deadlock:

"When two trains approach each other at a crossing, both shall come to a full stop and neither shall start up again until the other has gone."

A similar example is a livelock; the states of the processes involved in the livelock constantly change with regard to one another, none progressing. A real-world analogy would be two polite people trying to pass each other in a narrow corridor; on noticing that an impending resource conflict will occur (collision sense carrier detect, if you like), they both simultaneously move out of the way – and then back again with new collision potential. Both use up resources, are active, but progress no further.

Locks are currently manually inserted in typically programming languages; without locks programs can be put in an inconsistent state. They are usually included as a way of guarding critical sections. Multiple locks in different places and orders can lead to deadlocks. Manual lock inserts is error-prone, tedious and difficult to maintain. Does the programmer know what parts of a program will benefit from parallelisation? To ensure that parallel execution is safe, a task’s effects must not interfere with the execution of another task.

Optimisation: Do We Really Want It?

Knuth once famously wrote, "The real problem is that programmers have spent far too much time worrying about efficiency in the wrong places and at the wrong times; premature optimization is the root of all evil (or at least most of it) in programming." (Knuth, 1974) The words need to be considered in their totality. Knuth is not suggesting that we do not want to optimise our programs, but rather that efficiency gains should be sought at an appropriate time and place. The preceding text has illustrated the significant problems that can arise in attempts to make a program "go faster" when clarity would have been more important. Develop a clear program first and then seek to improve the efficiency of the code.

With a working program in place, consideration should be given to whether optimisation will add anything to the program, and a great deal of that comes down whether the optimisation is even necessary. A short script that is only going to be used a few times does not justify hours of additional programmer effort. One that is used many times a day with hefty data flows does. A very handy table was provided by Randall Munroe to illustrate the difference.

When optimising a program, whether with serial or parallel improvements it is generally much better to think in a top-down structure. Rather than debating with one's self whether an particular datatype is the best choice for efficiency, choose the safest first. Then look for big potential gains in optimisation; data flow structure, both within and oustide the program is a good one. As is the overall architecture (which will certainly affect data flow). Drilling down, looking at which datastructures provide the better performance or reduce overhead, ans specific algorithm choices. Finally, at the very end profiling specific parts of the code to identify potential areas of gain.

Amdahl's Law and the Gustafson-Barsis Law

Amdahl's law, in the general sense, is a method to work out the maximum improvement to a system when only part of the system has been improved. A very typical use - and appropriate in this context - is the improvement in speedup with the adding on multiple processors to a computational task. Because some of the task is in serial, there is a maxiumum limit to the speedup based on the time that is required for the sequential task - no matter how many processors are thrown at the problem. For example, if there is a complex one hundred hour which will require five hours of sequential processing, only 95% of the task can be parallel - which means a maximum speedup of 20X.

Thus maximum speedup is:

S(N) = 1 / (1-P) + (P/N)

Where P is the proportion of a program that can be made parallel, and (1 - P) is the proportion that cannot be parallelized (remains serial).

It seems a little disappointing to discover that, at a certain point, no matter how many processors you throw at a problem, it's just not going to get any faster, and given that almost all computational tasks are somewhat serial, the conclusion should be clear (e.g., Minsky's Conjecture). Not only are there serial tasks within a program, the very act of making a program parallel involves serial overhead, such as start-up time, synchronisation, data communications, etc.

However it is not necessarily the case that the ratio of parallel and serial parts of a job and the number of processors generate the same result, as the variation in execution time in the specific serial and parallel implementation of a task can vary. An example can be what is called "embarrassingly parallel", so named because it is a very simple task to split up into parallel tasks as they have little communication between each other. For example, the use of GPUs for projection, where each pixel is rendered independently. Such tasks are often called "pleasingly parallel". To give an example using the R programming language the SNOW package (Simple Network of Workstations) package allows for such parallel computations.

Let us consider the problem using a metaphor in a concrete manner; driving from Melbourne to Sydney. Because this an interesting computational task, the more interesting route is being taken via the coastline, rather than cross-country through Albury-Wodonga, which is quicker. For the sake of argument assume this journey is going to take 16 hours (it's actually somewhat less). Yes, a journey is taken in serial - but the point here is to illustrate the task rate.

At the half way point of this journey and 8 hours of driving there is a very clever mechanic, just outside Mallacoota, who has developed a dual-core engine which, as a remarkable engineering feat, allows a car to travel twice as fast (with no loss in safety etc). To use the computing metaphor, it completes the task twice a quickly as we also assume that the engine has been designed to split the task into two. The mechanic, clearly a very skilled individual, is able to remove the old single-core engine and replace it with a new dual-core instantly. Perhaps they are a wizard rather than a mechanic.

In any case, the second-half of the journey with the new dual-core engine now only takes 4 hours rather than the expected 8, and the total journey takes 12 hours rather than the expected 16. With the development of quad-core and octo-core engines the following journey time is illustrated.

Cores Mallacoota Sydney Total Time 1 8 hours +8 hours 16 hours 2 8 hours +4 hours 12 hours 4 8 hours +2 hours 10 hours 8 8 hours +1 hour 9 hours .. .. .. .. Inf 8 hours +nil 8 hours

Whilst the total journey time is reduced with the addition of new multicore engines, even an infinite-core engine cannot reduce the travel time to less than the proportion of the journey that is conducted with a single-core engine.

In very general terms Amdhal's Law states thaat the total maximum improvement to a system is limited by the proportion that has been improved. In computing programming because some of the task is in serial, there is a maxiumum limit to the speedup based on the time that is required for the sequential task - no matter how many processors are thrown at the problem.

The maximum speedup is:

S(N) = 1 / (1-P) + (P/N)

Where P is the proportion of a program that can be made parallel, and (1 - P) is the proportion that cannot be parallelised (and therefore remains serial).

Parallel programming is a complicated affair that requires some serial overhead. Not only are there serial tasks within a program, the very act of making a program parallel involves serial overhead, such as start-up time, synchronisation, data communications, and so forth. Therefore, all parallel programs will be subject to Amdahl's Law and are therefore limited in their total performance improvement, no matter how many cores they run on. The following graphic, from Wikipedia, illustrates these limits.

(Image from Daniels220 from Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)Whilst originally expressed by Gene Amdahl in 1967, it wasn't until over twenty years later in 1988 that an alternative to these limitations was proposed by John L. Gustafson and Edwin H. Barsis. Gustafon noted that Amadahl's Law assumed a computation problem of fixed data set size, which is not really what happens that often in the real world of computation. Gustafson and Barsis observed that programmers tend to set the size of their computational problems according to the available equipment; therefore as faster and more parallel equipment becomes available, larger problems can be solved. Thus scaled speedup occurs; although Amdahl's law is correct in a fixed sense, it can be circumvented in practise by increasing the scale of the problem.

If the problem size is allowed to grow with P, then the sequential fraction of the workload would become less and less important. Assuming that the complexity is within the serial overhead (following Minsky's Conjecture), the bigger the dataset, the smaller the proportion of the program that will be serial. Or, to use the car metaphor, why stop at Sydney? You have a multicore car now, just keep going! For their elegant and practical solution they won the 1988 they won the Gordon Bell Prize. Let's review that table again.

Cores Mallacoota Sydney Brisbane Rockhampton Total Time 1 8 hours +8 hours +8 hours +8 hours 32 hours 2 8 hours +4 hours +4 hours +4 hours 20 hours 4 8 hours +2 hours +2 hours +2 hours 14 hours 8 8 hours +1 hour +1 hour +1 hours 11 hours .. .. .. .. .. Inf 8 hours +nil +nil +nil 8 hours

As can be noted the overhead becomes proportionally less and less the further the distance travelled. Thus, whilst Amdahl's Law is certainly true in a fixed sense, data problems are often not fixed, and the advantages of parallelisation can be achieved through making use of Gustafon-Barsis Law. It should also be fairly clear how multicore computing, parallel programming, and big data converge into a trajectory for the future of computing. For most problems there is at least some parallelisation that can be conducted - and it's almost always worth doing if one can. The bigger the dataset, the greater the benefits.

Before delving into actual programming and debugging, the subject of the subsequent chapters, it is worth seriously considering best programming practises. There are a number of excellent texts already available on this subject and as a result only a summary is required here. In a nutshell, many people who have thought seriously about this subject have come to very similar conclusions.

Mytton's "Why You Need Coding Standards" (2004) provides good justifications on why one should have programming practises, and also documented standards if one is working in a team - and with the exception of people writing short scripts themselves, this should be the case for any programming project. In fact, even then some coding standards should be seriously considered. If one is writing scripts to do a particular thing, and that thing is useful, then chances are that other people will want to participate in developing it further. A useful script becomes a project.

Hence Mytton argues there is a deliberate emphasis on the term "maintainable code", in part asserting that code should be maintainable, and in part recognising that often it is not. Of course, this raises the question of what constitutes maintainable code. People tend to initially write in their own conventions, and those conventions may not be accessible to others. The objective should be that someone who is unfamiliar with the code can view it and, because there is clear layout with succinct comments that explain the constructs and workflow, that the newcomer has to spend less time learning individual styles and more time building and using the code.

Mytton's suggestion is a coding standard document, that states how developers must write their code. In a shared project this creates a shared grammatical structure so that the individual developers can understand what each other is doing. I would go a step further, and argue that individual coders should develop their own standards document, which enforces that they think about the style choices they have made, they remain consistent to it, and they can more easily convert to a a different standard.

Essentially, the standard should ensure the code is consistent and readable, with clearly defined "paragraphs" for blocks of code with different functions. Control statements should be indented to illustrate what block they apply to. Variables and functions should be named to describe what they are and what they do, respectively. Are the blocks properly commented according to functionality? Are there examples of code, which are quicker to write but affect readability? Does it affect performance?

Another text in this genre worth mentioning is Martin's "Clean Coder: A Code of Conduct for Professional Programmers" (2011). The subtitle is important, as it is central to the story. Being professional means being responsible for one's actions, which means making sure that one's code has been tested to the nth degree, that you know what it does, and you have protections to ensure that it doesn't break anything, and if it does, own up to it. To give an example Tony Hoare, one of the great early authors on developing a formal language for the correctness of computer programs, gave an apology at QCCon in 2009 for inventing the null reference, which he described as:

"... my billion-dollar mistake. It was the invention of the null reference in 1965.... My goal was to ensure that all use of references should be absolutely safe, with checking performed automatically by the compiler. But I couldn't resist the temptation to put in a null reference, simply because it was so easy to implement. This has led to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes, which have probably caused a billion dollars of pain and damage in the last forty years."

Martin argues that a professional should tell the truth, even and especially if that upsets their managers or supervisors. Managers are in the business of managing people, their expectations, and so forth; programmers are in the business of what is true. The two may be in conflict, but the former must prevail. The manager must think of a new strategy to satisfy the customer. The programmer must determine if the request is possible and coherent. On the other hand programmers, when they say 'yes', must really mean it and they will deliver on the commitment - and if they cannot that they'll raise the limitations with the manager, early. The manager, after all, has a job to do as well. Whilst coding, professional programmers should remove all distractions, whilst preparing they should seek to collaborate, and all cases develop with unit tests in mind, modify according to acceptance tests, and mentor others. If it sounds simple enough, ask yourself if you're doing it.

Finally there is Wilson et al (2014) who have an excellent paper "Best Practices for Scientific Computing". Here is a summary of their core principles, as the subheadings:

Summary of Best Practices

1. Write programs for people, not computers.

a. A program should not require its readers to hold more than a handful of facts in memory at once.

b. Make names consistent, distinctive, and meaningful.

c. Make code style and formatting consistent.

2. Let the computer do the work.

a. Make the computer repeat tasks.

b. Save recent commands in a file for re-use.

c. Use a build tool to automate workflows.

3. Make incremental changes.

a. Work in small steps with frequent feedback and course correction.

b. Use a version control system.

c. Put everything that has been created manually in version control.

4. Don't repeat yourself (or others).

a. Every piece of data must have a single authoritative representation in the system.

b. Modularize code rather than copying and pasting.

c. Re-use code instead of rewriting it.

5. Plan for mistakes.

a. Add assertions to programs to check their operation.

b. Use an off-the-shelf unit testing library.

c. Turn bugs into test cases.

d. Use a symbolic debugger.

6. Optimize software only after it works correctly.

a. Use a profiler to identify bottlenecks.

b. Write code in the highest-level language possible.

7. Document design and purpose, not mechanics.

a. Document interfaces and reasons, not implementations.

b. Refactor code in preference to explaining how it works.

c. Embed the documentation for a piece of software in that software.

8. Collaborate.

a. Use pre-merge code reviews.

b. Use pair programming when bringing someone new up to speed and when tackling particularly tricky problems.

c. Use an issue tracking tool.

Sometimes these principles could be in conflict. For example, item 4b explicitly says not to copy-and-paste. Yet a quotation like this is a copy-and-paste. Perhaps a reference or a URL could be provided to the authoritative source instead (indeed, it will be found in the reference section). However, there is also the principles embodied in 1a. If this section simply said "go read this paper", most people (and probably including yourself, gentle reader) would have thought to themselves, "I'll do that later" and it wouldn't happen. We humans like to read in serial even when hyperlinks are available. With appetite whet, the emphasis is made, this is the only time I will say this: Please read the paper now, carefully, and take notes. Then return to this text.

Once one has a good grasp of the conventions for coding practises then one has to develop good programming. Again, it is only possible to touch upon this in brief and refer the reader to some other excellent sources. Because logical and mathematics remains pretty consistent it is possible to recommend a text as old as 1970, well recognised as a classic in the subject specifically E.W.Dijkstra's "Notes on Structured Programming" (1970), the URL of the PDF in this book's references. "Notes" emphasises the need to testing, structured design, enumeration and induction, abstraction, decomposition of problems and composition of programs, conditionals and branching, comparison of programs, the use of number theory in programming, families of related programs, system and programmer performance, and arrangement of layers corresponding to abstraction. If all of this seems familiar, that's because the principles have become commonly accepted in computer science. That's why it's a classic!

Another example of a classic is "The Elements of Programming Style" (Kernighan, Plauger, 1978). The name is deliberately designed to invoke a reference to the more famous "The Elements of Style" by Strunk and White for writers, and makes the observation that sometimes the rules are broken by the best programmers, but when they do there is a greater benefit in breaking the rule rather than keeping it. In most cases however, keeping the style rule is preferred. What are their style rules? Clarity in coding is better than cleverness. Code re-use through libraries and common functions is essential. Avoid too many temporary variables. Select unique and meaningful variable names and ensure variables are initialised before use. Break down big problems into smaller pieces, structure code with procedures and functions that do one thing well, and avoid goto statements. Re-writing bad code is preferential to patching. Use recursive procedures for recursively-defined data structures; it doesn't save time or storage, it is for clarity. Test for plausibility and validity and check the validity of inputs in the code, using EOF markers. Make use of debugging compilers, check boundary conditions, look out for off-by-one errors, and don't confuse integers and reals. Performance is secondary to functional. Comments should be judicious, should agree with the code, and the code should be formatted for readability.

There is also Niklas Wurth's "Algorithms and Data Structures" (Wurth, 1985), which does as it says on tin, outlining the particular advantages and disadvantages of each in each context, and understandably makes extensive use of the Pascal and Modula-2 programming languages, depending on edition. Despite the order of the title, Wurth is insistent that data precedes algorithms. Thus one initially finds a comparison between standard primitive types (real, boolean, char, set), the structure and representation of arrays and records, files, searching through linear approaches, binary approaches, and tables, sorting arrays and sequences, recursion, dynamic information such as recursive data types, and pointers, and hashing functions. Wurth argued that "many programming errors can be prevented by making programmers aware of the methods and techniques which they hitherto applied intuitively and often unconsciously", and by implication, many errors are made when they are not consciously aware of the methods and techniques.

Taking a second bite at the cherry, Martin's "Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship" (2009) can be read alongside "Clean Coders" (2011). The opening chapter points to the re-writing or maintenance costs of "owning a mess"; prevention is cheaper. After this it argues for meaningful names - in filenames, variables, functions etc. In addition to be meaningful, they should also be distinct, searchable, and use one word per concept. Martin argues "don't pun", however puns can be meaningful, insightful, and most importantly, memorable. Functions should be small, do one thing, have one level of abstraction, and have no side effects. Comments should include legal provisions, explanation of intent, clarifications, warnings, and to-do comments. The comments on formatting emphasise readability on the vertical and horizontal axes, and the use of "team rules". Management of objects and data structures should be based on the realisation that objects expose data and hide data, whiile data structures expose data but have no behaviour; objects are preferred if one wants to add new data types, and new data types are preferred if you want new behaviours. In error handling, making use of exceptions rather than return codes, and don't pass or return null.

Use of boundaries should be part of a program's structure, especially when using third-party code. Unit tests should kept clean, with one concept per test. Classes should be small, organised with encapsulation, and isolated which allows for change. Concurrency allows for a separation between what gets done and when it gets done, and properly designed can improve performance, but must be based around defensive programming to avoid the problems resulting from race conditions. Concurrency is also a the subject of lengthy appendix in the book. In addition there is discussion on refinement of existing code, and plenty of heuristic examples of the principles described. If all of this seems to be a bit fleeting, that's because it is. In two paragraphs, this is only a thousand metre view of a book that is over four hundred pages of glorious detail. Read the book.

Take an opportunity to read the website suckless.org, "software that sucks less" and take in the principles, "simplicity, clarity and frugality". Beautiful software is not based on lines of code, just as more words does not make you a better author. Those three principles will create software that is efficient, robust, stable, maintainable, and very importantly, "plays nice with others".

Often I have said in various training courses: "Programming is hard. Parallel programming is very hard. Quantum programming is impossible". This is quite serious. Programming is a difficult task that involves an incredible attention to the logical workflow of various activities and then the processes of optimisation to improve clarity, performance etc. This is why Ken Thompson, of the creators of UNIX and C once remarked: "“One of my most productive days was throwing away 1000 lines of code." (in Raymond, E. "The Art of UNIX Programming").

Programming is not easy. Deciding to make a serial program run in parallel will make a lot more difficult, not just in identification of the the parts that can be possibly run in parallel, or the addition of new pragmas or routines, but especially in the process of debugging. Think hard about race conditions; and then think about them again.

As for quantum computing, this is not just meant as a throw-away line designed to generate some mirth (although, I readily admit, the humour of the progression has contributed). Certainly quantum computing does exist which, in a sense, means that it is technically incorrect. The question that the statement poses quite seriously is whethere there will ever be a useful quantum computer. Unlike a standard bit which has a "1" or "0" state ("high" and "low"), a quantum computer represents the equivalent, the qubit, as a continuum for both states and both simultaneously. Certainly, that's a challenging idea, but so is quantum mechanics. The problem is that the sheer size of a useful quantum computer which can express not just the variables but the logical flow must be improbably large. I might be wrong about this, but I'm sticking to the statement for the time being: Quantum computing is impossible.

Fortran and C are two of the most deployed programming languages in existence. Whilst languages do rise and fall in popularity, these two in particular have been in use since 1957 and 1972 respectively and are still in very active development. For those interested in scientific or high performance computing in particular, there can be little doubt that these will be of primary use for a significant period of time into the future, as they are they primary languages for implementations of shared memory parallelism (OpenMP) and message passing (MPI). Both languages are sufficiently important to have standards established by the ISO. Certainly they are not recommended for all programming activities; in many cases a simpler language such as a shell script, perl, python etc will be sufficient. But when it comes down to complex data structures, speed, and parallel processing, C and Fortran are the preferred choice.

The purpose of this chapter is not so much to provide an in-depth overview of the two languages. There are already many books that do this and are excellent in this regard. For C, the classic is The C Programming Language by Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie (1978), although to be compatiable with the ANSI stanard the second edition (1988) is recommended. The C Programming Absolute Beginner's Guide by Greg Perry and Dean Miller (2013) is an excellent introduction to the language as well. More advanced content can be found in Mastering Algorithms with C by Kyle Loudon (1999). For Fortran an excellent overview is available in Fortran 90/95 Explained by Metcalf an Reid (1996, second edition, 1999). As one encounters older code Upgrading to Fortran 90 by Redwine (1995) will provide the examples necessary to navigate. For more advanced examples, Numerical Recipes Example Book (Fortran) 2nd Edition by Press (1992) provides annotated examples of various subroutines; a C version is available as well.

Instead, the purpose of this chapter it is to provide a sufficient grounding that a reader who is unfamiliar with programming in these languages, but does have a little bit of programming experience, is able to follow the code examples. More importantly at this stage however is the conceptual grounding provided in placing C and Fortran within the wide range of programming languages available, and in particular providing various suggestions on coding practice that should be followed for programs of any level of complexity. Whilst this important for sequential programs, it is absolutely critical for any parallel programs.

Both Fortran and C have a particular history and implementations. As mentioned, Fortran was first implemented in 1957 by IBM and was quickly adopted as it was relatively easy to program and had a performance comparable to programs written in assembly language. Early versions included support for procedural programming. A significant development occurred in 1966 with a ANSI standard release, which would be elaborated in 1978 (known as FORTRAN77) with a release that supported structured programming with block statements. Early version of FORTRAN required six spaces before any commands were declared for operations with punch-card systems.

The next major release was Fortran90 (ISO/IEC standard in 1991 and ANSI in 1992) which allowed free-form source and modular programming. Since then there has been a minor revision with Fortran95, a major revision with Fortran 2003 (ISO/IEC release in 2004), which included object-orientated programming and interoperability with C, and a minor release in 2008. Contemporary implementations are found in many compiler suites, such as the Gnu Compiler Collection (GCC), Intel, and the Portland Group.

With regards to C, early implementations were limited to a small range of systems, and strongly tied to the development of the Unix operating system whose kernel was largely written in C. An informal standard was established with the first edition of The C Programmig Language by Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie in 1978. In 1983 the American National Standards Institute began a process for standardisation which was completed in 1989, with formatting changes endorsed by the ISO/IEC in 1990. A minor amendment was introduced by both bodies in 1995, and a minor revision in 1999. Unicode support and improved multi-threading was introduced with a revision in the ISO/IEC 2011. Like Fortran, contemporary implementations are found in many compiler suites, such as the Gnu Compiler Collection (GCC), Intel, and the Portland Group. As is well known, there are a number of programming languages that have been heavily influenced from C, including C++, Objective C, and Java.

It is commonly, if incorrectly, stated that languages like C and Fortran are compiled languages as opposed to interpreted. Strictly speaking this is not quite true, as any programming language can be compiled or interpreted. Rather compilation or interpretation are implementations of a language, rather than an attribute of the language. Nevertheless, it is true to say that C and Fortran programs are typically compiled and are operated with the executable binary from the compiled source code, rather than having an interpreter performing operations from the source code, executing each step directly on the way. Interpretation does have some advantages, which will be explored in this book, but speed is not one of them.

Contemporary Fortran and C programming is often described as imperative, procedural, and structured. In imperative programming algorithms are implemented in explicit steps to change the program's state. This is often contrasted with declarative programming, that express the logic of a computation without describing its control flow, leaving that to the specific language. By procedural programming what is meant is a sub-type of imperative programming where the the program is built from one or more procedures (also referred to as routines or functions). The significant change in procedural programming is that state changes can be localised; this technique would provide the foundation for object-orientated programming.

Finally, contemporary Fortran and C can both described as using a structured programming style. This makes extensive use of procedures and block structures rather than conditional jump branching (e.g., the goto statement). Structured programming is now extremely common to high level programming languages, as it is a powerful aid to readability and code maintenance. Structured programming also allows for greater ease in the development of pseudo-code, which should be requisite in any program of a non-trivial size, as it can replace non-unique expression calls to common functions. Writing pseudo-code should also be an aid for clarity in the program; programs that sacrifice clarity for cleverness are difficult to maintain.

An important attribute of programming languages is the implementation of types. These are the rules that the assign properties and interfaces to a variety of common constructs, such as variables, expressions, procedures, etc, which are then checked at compilation (static type checking), at run time (dynamic type checking), or a combination thereof depending on the construct. In principle typing prevents logical errors (particularly of the 'not even wrong' variety e.g., 2 + zebra / glockenspiel = homeopathy works!) and memory errors. Both C and Fortran check their typing at compilation, and are therefore statically typed. They both use manifest typing which requires explicit type identification by the programmer, rather than deducing the type from context or dynamically assigning it at runtime. With these contributions, C and Fortran are often colloquially classified as 'strongly typed', meaning that they are likely to catch type errors when compiled.

The examples throughout this chapter will use the GNU compiler suite version 5.2.0 (2015). Note that the assumed suffix for Fortran90 is .f90 – if you attempt to compile with just .f, the compiler will assume you're using FORTRAN77.

The classic 'Hello World' example can be expressed as source in Fortran and C as follows.

In Fortran

program hello

implicit none

print *, "Hello world!"

end program hello

In C

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

printf("Hello, world!");

return 0;

}

Both can be compiled respectively as follows, with the source file (.c or .f) creating an executable binary:

`gfortran hello.f90 -o hellof`

`gcc hello.c -o helloc`

Which can be run by invoked ./hellof or ./helloc as appropriate from the executable directory.

The basic compilation command runs the against a text files with the correct suffix (i.e., .c, .f90). In this situation the source files are assembled but not linked. Assuming that compilation is successful however, the compiled version is left in a file called a.out However it usually far more convenient to use a -o and filename in the compilation to specify an output executable binary. The compiler translates source to assembly code, and the assembler creates object code (represented with the .o suffix). The link editor then combines and references library functions in other source files, creating an executable.