At Yahoo, we built this high throughput, low latency distributed key-value database that runs in multiple data centers in different parts for the world. The database stores billions of records and handles millions of read and write requests per second with an SLA of 1 millisecond at the 99th percentile.

The data we have in this database must be persistent, and the working set is larger than what we can fit in memory. Therefore, a key component of the database’s performance is a fast storage engine, for which we have relied on Kyoto Cabinet. Although Kyoto Cabinet has served us well, it was designed primarily for a read-heavy workload and its write throughput started to be a bottleneck as we took on more write traffic.

There were also other issues we faced with Kyoto Cabinet; it takes up to an hour to repair a corrupted db, and takes hours to iterate over and update/delete records (which we have to do every night). It also doesn't expose enough operational metrics or logs which makes resolving issues challenging. However, our primary concern was Kyoto Cabinet’s write performance, which based on our projections, would have been a major obstacle for scaling the database; therefore, it was a good time to look for alternatives.

These are the salient features of the database’s workload for which the storage engine will be used:

- Small keys (8 bytes) and large values (10KB average)

- Both read and write throughput are high.

- Submillisecond read latency at the 99th percentile.

- Single writer thread.

- No need for ordered access or range scans.

- Working set is much larger than available memory, hence workload is IO bound.

- Database is written in Java.

Although there are umpteen number of storage engines publicly available almost all use a variation of the following data structures to organize data on disk for fast lookup:

- Hash table: Kyoto Cabinet.

- Log-structured merge tree: LevelDB, RocksDB.

- B-Tree/B+ Tree: Berkeley DB, InnoDB.

Since our workload requires very high write throughput, Hash table and B-Tree based storage engines were not suitable as they need to do random writes. Although modern SSDs have narrowed the gap between sequential and random write performance, sequential writes still have higher throughput, primarily due to the reduced internal garbage collection load within the SSD. LSM trees also turned out to be unsuitable; benchmarking RocksDB on our workload showed a write amplification of 10-12, therefore writing 100MB/sec to RocksDB meant that it will write more than 1 GB/sec to the SSD, clearly too high. High write amplification of RocksDB is a property of the LSM data structure itself, thereby ruling out storage engines based on LSM trees.

LSM tree and B-Tree also maintain an ordering of keys to support efficient range scans, but the cost they pay is a read amplification greater than 1, and for LSM tree, very high write amplification. Since our workload only does point lookups, we don’t want to pay the cost associated with storing data in a format suitable for range scans.

These problems ruled out most of the publicly available and well maintained storage engines. Looking at alternate storage engine data structures led us to

explore ideas used in Log-structured storage systems. Here was a potential good fit; log-structured system only does sequential writes, an efficient

garbage collection implementation can keep write amplification low, and having an index in memory for the keys can give us a read amplification of one,

and we get transactional updates, snapshots, and quick crash recovery almost for free. Also in this scheme, there is no ordering of data and hence its

associated costs are not paid. We found that similar ideas have been used in BitCask

and Haystack.

But BitCask was written in Erlang, and since our database runs on the JVM running Erlang VM on the same box and talking to it from the JVM is something

that we didn’t want to do. Haystack, on the other hand, is a full-fledged distributed database optimized for storing photos, and its storage engine hasn’t been open sourced.

Therefore it was decided to write a new storage engine from scratch; thus the HaloDB project was initiated.

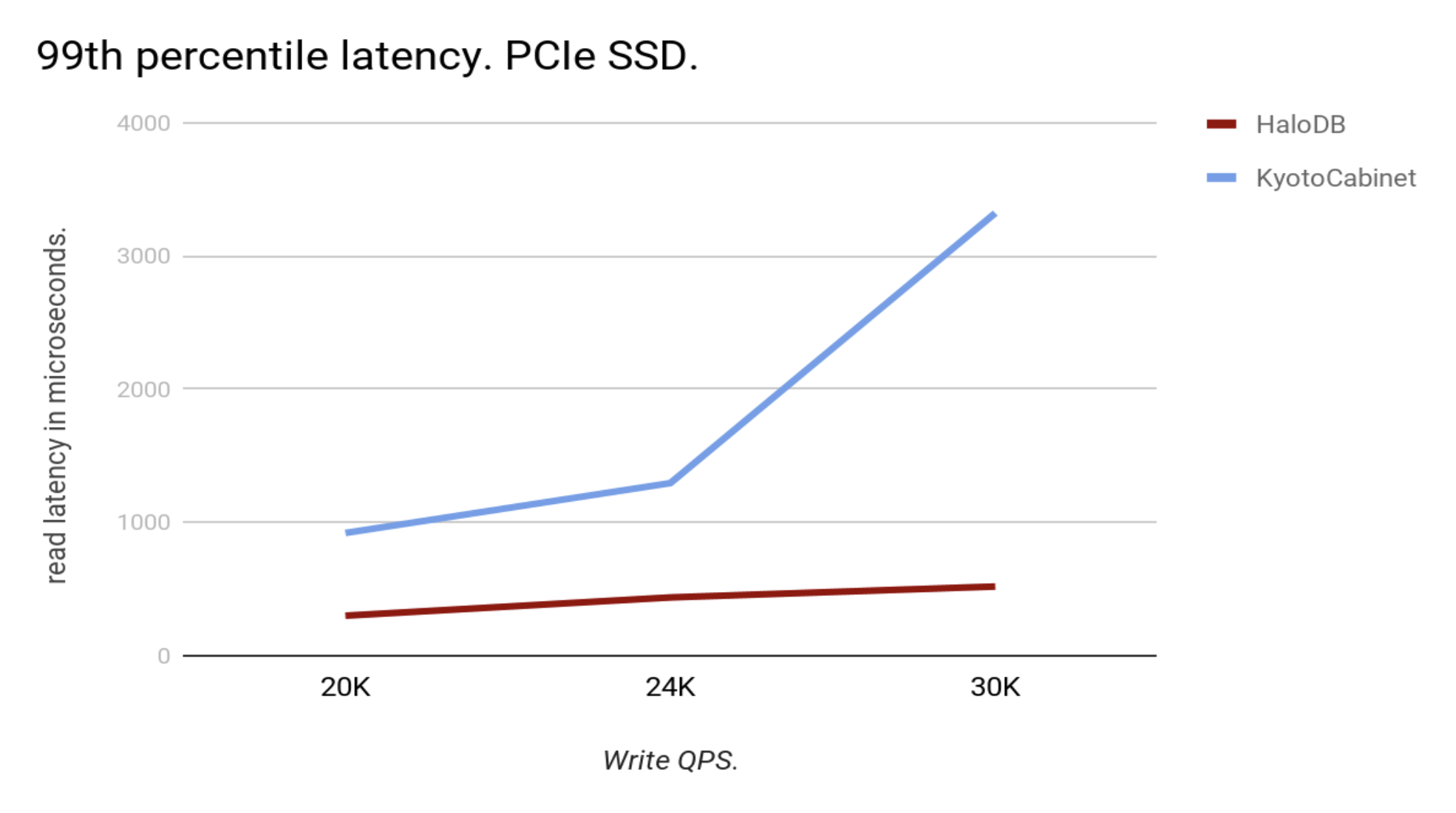

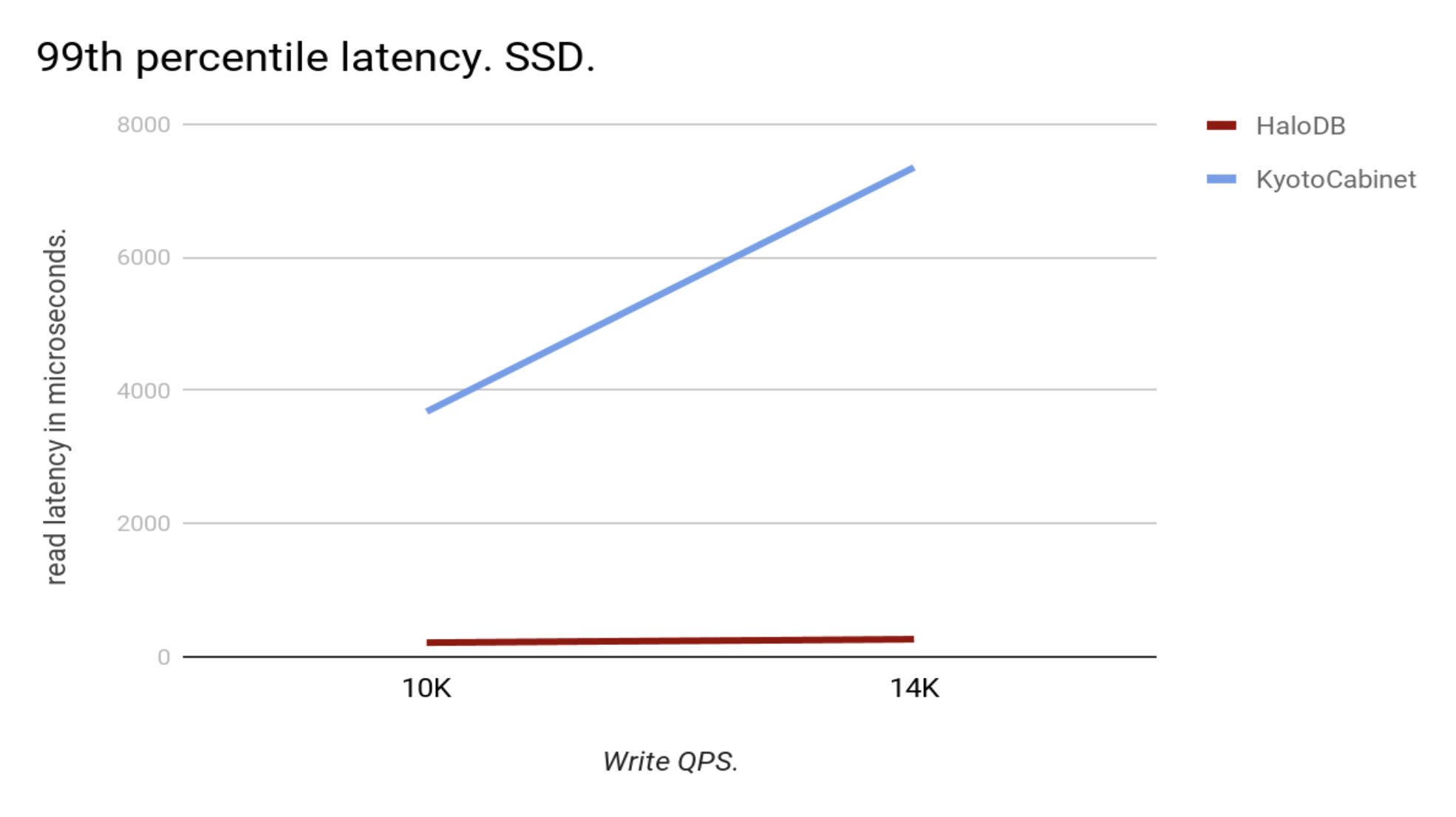

The following chart shows the results of performance tests that we ran with production data against a performance test box with the same hardware as production boxes. The read requests were kept at 50,000 QPS while the write QPS was increased.

As you can see at the 99th percentile HaloDB read latency is an order of magnitude better than that of Kyoto Cabinet.

We recently upgraded our SSDs to PCIe NVMe SSDs. This has given us a significant performance boost and has narrowed the gap between HaloDB and Kyoto Cabinet,

but the difference is still significant:

As you can see at the 99th percentile HaloDB read latency is an order of magnitude better than that of Kyoto Cabinet.

We recently upgraded our SSDs to PCIe NVMe SSDs. This has given us a significant performance boost and has narrowed the gap between HaloDB and Kyoto Cabinet,

but the difference is still significant:

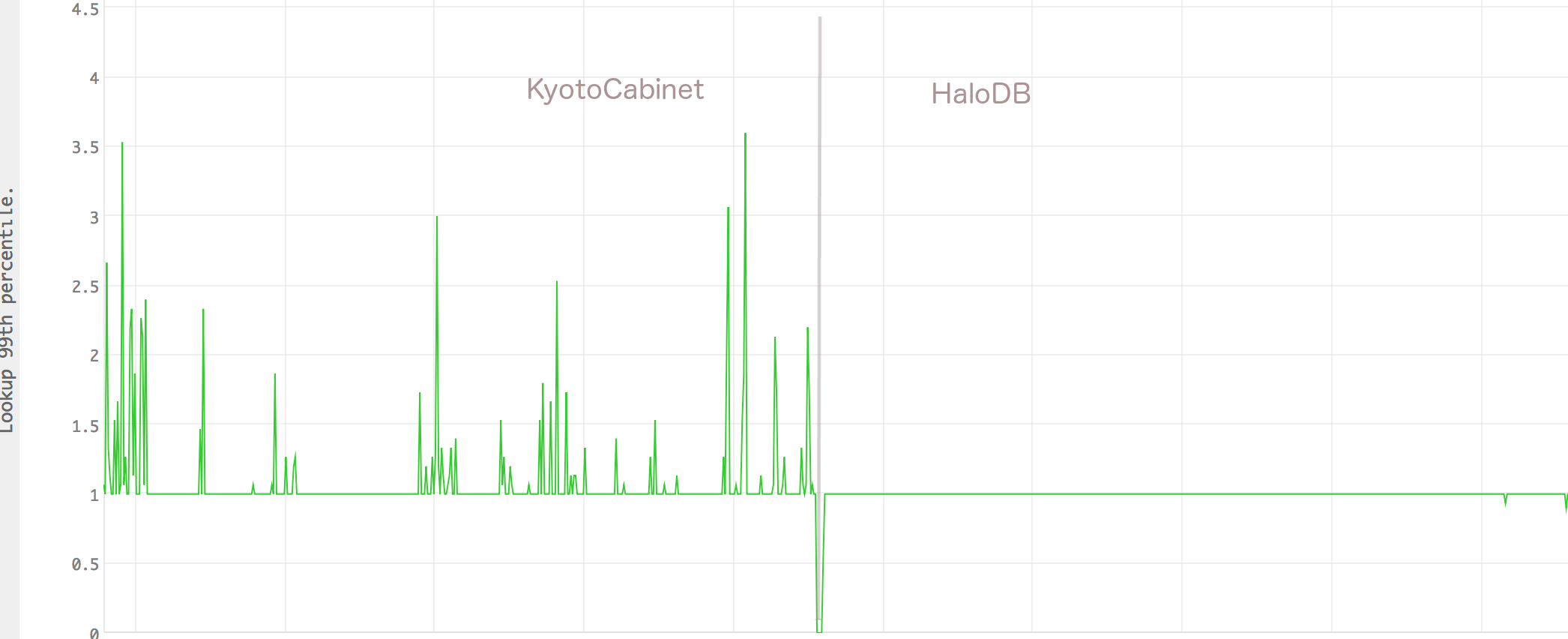

Of course, these are results from performance tests, but nothing beats real data from hosts running in production. Following chart shows the 99th percentile latency from a production server before and after migration to HaloDB.

HaloDB has thus given our production boxes a 50% improvement in capacity while consistently maintaining a sub-millisecond latency at the 99th percentile.

HaloDB also has fixed few other problems that we had with KyotoCabinet. The daily cleanup job that used to take upto 5 hours in Kyoto Cabinet is now complete in 90 minutes with HaloDB due to its improved write throughput. Also, HaloDB takes only a few seconds to recover from a crash due to the fact that all log files, once they are rolled over, are immutable. Hence, in the event of a crash only the last file that was being written to need to be repaired. Whereas, with Kyoto Cabinet crash recovery used to take more than an hour to complete. And the metrics that HaloDB exposes gives us good insight into its internal state, which was missing with Kyoto Cabinet.